Optimizing Your Author Website or Blog

Andy Warhol talked about “15 minutes of fame,” and that’s what happens to most content posted on author websites or blogs. An author writes a blog post and shares it with her communities. It may have a bit of success, but then it disappears into the billions of pages on the Internet, never to be seen again.

But that doesn’t have to happen.

Instead of being an abandoned grave, your blog posts can be the Taj Mahal, still a mausoleum, but with a lot more visitors. The truth is you don’t have to be a J.K. Rowling to get a steady stream of visitors to your website.

The key is slightly modifying your content in order to optimize for a few big platforms. This is greasing the wheel–taking your already good content and modifying it slightly, to create constant (or increasing) readership over time. In this blog series I will focus specifically on what you can do to your content itself. Marketing your website and yourself would be another series of blog posts by itself.

The Outline

Part 1 (this post) discusses why optimizing your author website is important. I’ll use examples from my own blog and introduce general principles, including the 4 S’s of good content.

Part 2, Google, highlights 10 easy ways to optimize you author blog/website for Google.

Part 3, Facebook, discusses 6 easy ways to optimize for Facebook.

Part 4, Pinterest, focuses on 8 easy ways to optimize for Pinterest.

This post is based on a presentation I gave at Tech PHX in November 2014. Many of the better ideas are borrowed from my husband, Scott Cowley, an internet marketer who spent years working in Search Engine Optimization (SEO). He’s currently pursuing a PhD in Marketing with a focus on Internet and Digital Marketing, and he approves the principles I discuss in these posts.

Case Study: My Website

I’ve owned this domain for quite a while, but it was in January 2013 that I decided to really launch it as an author website. An at that point I was an unpublished author, and unless you’re famous for something else, as an unpublished author you have absolutely no audience.

I revamped the design of my website and during January and February I wrote 8 blog posts. I installed Google Analytics so I could track my website’s performance. And in February 2013, after promoting my website to all my friends and family, I received:

- 127 unique visitors

- 250 page views

I have not been a prolific blogger: I’ve published, on average, 1.6 posts per month. Yet last month, in May 2015, I received:

- 2344 unique visitors

- 3111 page views

I have never had a post go viral, and my audience is still a fraction of what I want it to be. But with a handful of hours a month, the size of my audience has increased over 18 times. And while I’ve published a number of short stories, most of this traffic increase is due directly to optimizing my website, specifically for Google, Facebook, and Pinterest.

Some of this has happened unintentionally. One of all-time most visited blog posts is a humorous post titled “My Companion Llama.”

For a while if you searched for “companion llama” on Google I was ranked number 1 for the term. Fortunately I’ve dropped down to number 4, which is a good because most people searching for companion llamas are interested in getting their own companion llama, and not in reading a mildly mocking piece. But out of habit, I optimized for the term “companion llama,” and there wasn’t much competition, so I’m still ranking for it.

Most of my other blog posts I’ve intentionally optimized.

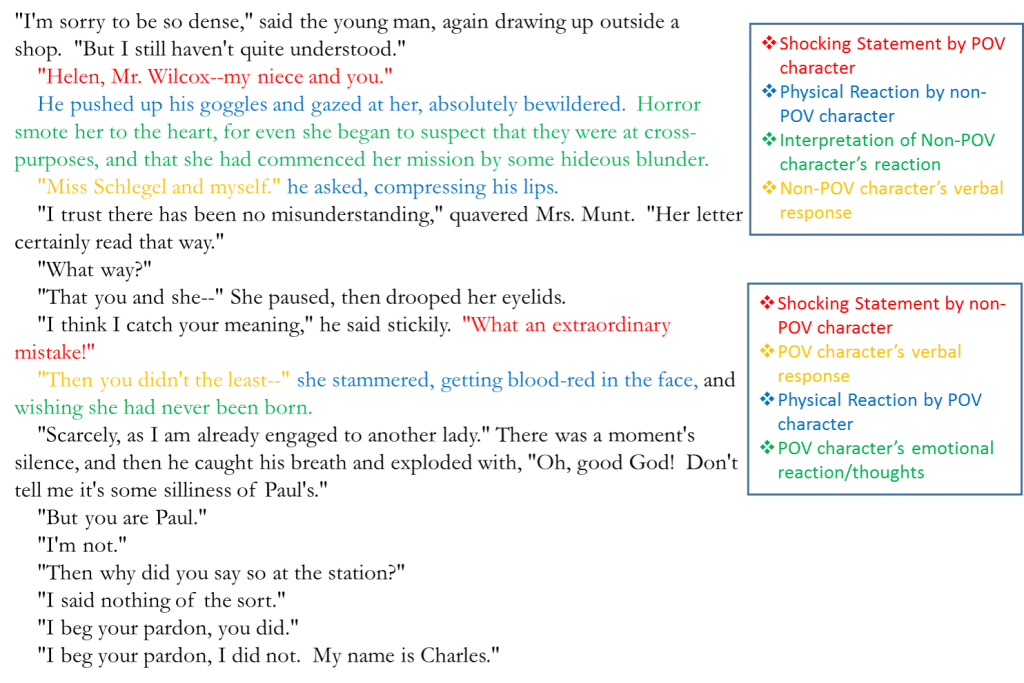

On the day I published “10 Keys to Writing Dialogue in Fiction,” I shared it on Facebook. Most of my friends aren’t interested in writing craft, and I received only 29 views. Honestly, that’s a little depressing. But because I optimized the post, since then I have received over 12,000 views on the blog post, and the number of readers continues to increase every single month.

How did I do it? First, let’s look at the big picture, the general principles.

The 4 S’s of Good Content

As you create your author website and add new blog posts, your content should be stimulating, searchable, shareable, and savable.

The first S is Stimulating.

If your content isn’t good, it doesn’t matter how much you optimize.

But how do you figure out what content will be stimulating for your audience?

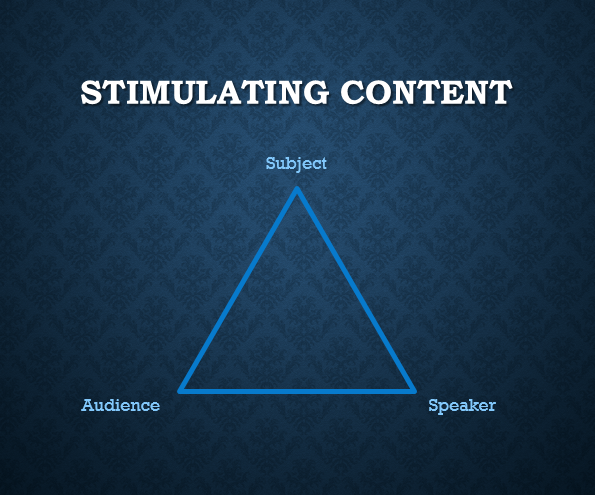

My favorite advice on this subject actually comes from Aristotle. He wrote a book titled On Rhetoric over 2000 years ago. He focuses on three things in his text, which modern scholars call the rhetorical situation, or the rhetorical triangle.

What is your subject matter? What does your audience look like, what do they care about, and what connects to them? And what makes you distinctive as a speaker or writer, that you can offer? Figuring out how the subject, the audience, and the speaker intersect is key to creating stimulating content. I could write a whole series of blog posts on this subject, but that will have to wait for another day.

Searchable, Shareable, and Savable

Once you have stimulating content, the next three s’s relate to optimizing your website and blog. Unless you want your content to die an early death, it must be searchable, shareable, and savable.

Searchable: Your content needs to be searchable by Google and other search engines. Pinterest and other platforms also provide search functions that drive a lot of traffic. If you are not receiving traffic by organic search, you are missing out on a huge opportunity.

Shareable: You have to package your content in such a way that people can share it easily and effectively. People are sharing content constantly on social media sites including Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest.

Savable: People want to be able to come back to your content easily, but most aren’t going to use a traditional browser bookmark or create a list of links in a word file. People will save your content on Pinterest, Tumblr, and Facebook and they will come back to it later and return to your website.

Parts 2, 3 and 4 of this series will go in depth on easy, practical things you can do to make your author website searchable, shareable, and savable.

Moving Forward

Depending on what study you’re consulting, organic search (from Google and other search engines) accounts for 50-64% of website visits. It is the largest driver of web traffic. So that is the focus of Part 2:

Optimizing Your Author Website or Blog for Google

Related:

Part 3: Optimizing for Facebook

Part 4: Optimizing for Pinterest

(These follow-up posts will be published in the coming weeks.)

Image Credits:

Pen and notebook – Ray Sadler via flickr, Creative Commons license; Cemetery – Berit Watkin via flickr, Creative Commons license; Taj Mahal – Francisco Martins via flickr, Creative Commons license; Lllama – Mary via flickr, Creative Commons license; Will Write for Food – Ritesh Nayak via flickr, Creative Commons license.

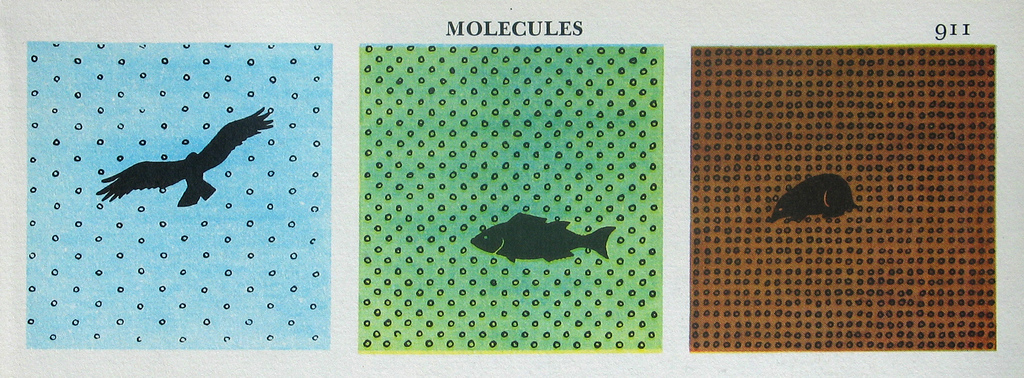

A metaphorical depiction of molecules, from The Golden Book Encyclopedia, 1959. Image Credit:

A metaphorical depiction of molecules, from The Golden Book Encyclopedia, 1959. Image Credit:

This essay received second place in the BYU Studies 2013 Essay Contest. Original image of typewriter by

This essay received second place in the BYU Studies 2013 Essay Contest. Original image of typewriter by