Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#5: Make Things Hard for Your Character

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

In the film Austenland, the main character, Jane, goes shooting with the other guests at an Austen-themed resort. On the way back, her horse refuses to budge, so the others go on without her. She waits alone, and then begins walking back by herself. To make things worse, it begins to rain. Actually, pour.

Mr. Nobley comes to rescue Jane, but her troubles are not over: her skirt’s in the way (he helpfully rips it for her); when they get back, she has trouble getting off the horse and falls awkwardly over Mr. Nobley; finally, Lady Amelia Heartwright ignores Jane and then, once she notices her, she is appalled by her appearance.

The film is delightful and hilarious, in part because there is no end to Jane’s troubles. It’s not just horse trouble, or the rain, or the skirt—it’s obstacle building on obstacle, with small triumphs interspersed (she does, after all, manage to get off the horse).

I used to be afraid to hurt my characters, which greatly limited my stories. Challenge creates the potential for growth.

A great example of a character experiencing hard things is Anne Elliot in Persuasion. She is taking a long walk with a number of family members and friends, including her ex-fiancé Captain Wentworth (who still isn’t over the fact that she broke up with him a decade before), and his current love interest, Louisa Musgrove.

At one point, Anne decides to rest on the hill. Her location accidentally places her in a spot where she is forced to eavesdrop on Captain Wentworth and Louisa’s budding romance. This certainly qualifies as making things hard for your main character.

As we analyze this scene, we can see Austen implementing three different techniques that are used to make things difficult for characters:

- Provide external obstacles and challenges that require action and must be overcome

- Give the character successes or triumphs which lead to complications or other difficulties

- Use the character’s internal flaws or challenges to make it harder for the character to succeed

External Obstacles and Challenges

External obstacles can be created by other characters, nature, animals, society, technology—in other words, by anything outside of the character’s self.

Anne Elliot still loves Captain Wentworth, so in this scene the external challenge is caused by the romance between Captain Wentworth and Louisa, and by the fact that Anne is forced to witness it. At one point, Wentworth praises Louisa in a way that Anne knows is a direct critique of Anne’s own character and past choices:

“My first wish for all, whom I am interested in, is that they should be firm. If Louisa Musgrove would be beautiful and happy in her November of life, she will cherish all her present powers of mind.”

Anne does not take immediate action against this obstacle, but it is an obstacle that she must overcome over the course of the novel.

Successes or Triumphs

Seemingly good things—successes and triumphs—can also make things harder for the main character. This is counterintuitive because we expect good things to yield good results, yet good things can have a myriad of challenging results, including shallow victories, greater expectations/responsibilities, complicated relationships, and distractions from the real goal.

Not long after Anne eavesdrops on Wentworth and Louisa, the entire group reconvenes and begins the arduous journey home. Captain Wentworth goes out of his way to help Anne by securing her the only spot in a carriage for the ride home, and physically lifting her into the carriage, which could be considered a success or triumph for Anne. Yet this makes things more difficult for her:

This little circumstance seemed the completion of all that had gone before. She understood him. He could not forgive her, — but he could not be unfeeling. Though condemning her for the past, and considering it with high and unjust resentment, though perfectly careless of her, and though becoming attached to another, still he could not see her suffer, without the desire of giving her relief….[It] was a proof of his own warm and amiable heart, which she could not contemplate without emotions so compounded of pleasure and pain, that she knew not which prevailed.

The novel Persuasion provides many examples of how successes and triumphs can lead to further complications or other difficulties for the main character.

Internal Flaws and Challenges

Internal flaws and challenges also make it harder for characters to succeed at their goals.

During the first half of the novel, Anne’s internal flaws dominate: she still loves Captain Wentworth, but she is not assertive, and she does not make any clear attempts to show her affection to him.

Throughout this scene, Anne places herself and her desires beneath those of others, and she goes out of the way to avoid moments of interaction with Captain Wentworth. Despite her love, she intentionally avoids opportunities which could lead to them rekindling their friendship and romance:

Anne’s object was, not to be in the way of any body, and where the narrow paths across the fields made many separations necessary, to keep with her brother and sister.

Internal flaws and challenges are often harder for characters to overcome than any external obstacles.

In Conclusion

Making things hard for your character creates tension and conflict. It also makes the ultimate triumph of the character more compelling, because of all that they have had to overcome in the process.

In crafting hard things, it is important to avoid making the hard things too big or irrelevant. This scene with Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth doesn’t need an earthquake or an angry villain to make things harder for Anne, because in this scene, these little challenges are emotionally relevant. Austen doesn’t shy away from big events and challenges—for example, Louisa’s terrible fall later in the book—but building to these larger events with other smaller challenges makes them more emotionally resonant.

Exercise #1: Consider what external challenges a character might face when purchasing vegetables. Make a list of at least two large challenges, two medium challenges, and two small challenges they could face. Now choose a few of these challenges and write a paragraph about this character purchasing vegetables. If you would like, share this paragraph in the comments.

Exercise #2: Make a list of some of your own characteristics that might be considered flaws (being prone to anger, perfectionism, etc.). Write a paragraph about a time in your life when one of these characteristics made doing something more difficult for you.

Exercise #3: Take a scene that you have written. Underline or circle all the things that are hard for your character, and label each of the things as an external obstacle/challenge, a success/triumph which leads to other difficulties, or an internal flaw/challenge. Now read through the scene again and consider whether or not you need to add more challenges, big or small.

#4: Create an External Journey for Your Character

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

Once your character wants something and there is an inciting incident that starts them on their journey, then the next step is to take them on that journey. Fortunately, we have a long tradition of studying how story works. Over two thousand years ago, Aristotle wrote about dramatic structure in The Poetics. For something to be a story, he explained, there must be a beginning, a middle, and an end. This movement through the beginning, middle, and end of a story typically takes the form of a complication followed by an unravelling.

Fast forward several thousand years to Gustav Freytag, who was a German playwright and novelist. He built on Aristotle’s sense of complication and unravelling, or rising and falling action, in a book titled Die Technik des Dramas (which in English is translated as Freytag’s Technique of the Drama). While there are many other theorists and writers who have presented useful models that explain how plot works (there are three act structures, four act structures, seven point structures, and Campbell’s hero’s journey, to name a few), we’re going to stick with a modified Freytag’s Pyramid for this lesson.

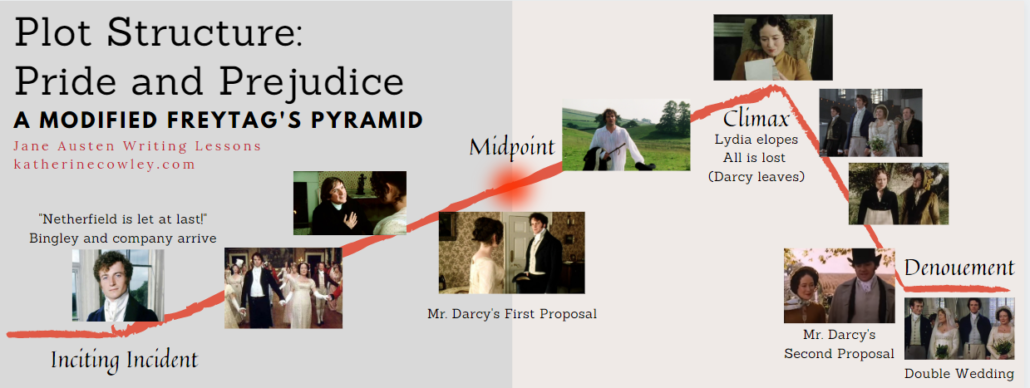

Understanding how the pyramid works can help you if you’re planning a novel. It is also useful during the revision process, because it can help you hit the key aspects of a story that readers expect and love. As an example, we’re going to analyze the plot structure of Pride and Prejudice.

The Exposition

The exposition is the story world in stasis, or as it existed before the inciting incident. For some books, this takes several chapters, for others, a few sentences, and for other stories, we start with the inciting incident and the exposition is delivered through little pieces of interspersed backstory.

In Pride and Prejudice, not much time is spent on exposition at all—news of the inciting incident is delivered on the very first page. Yet the backstory is made clear nonetheless: we understand who these characters are, we quickly grasp the nature of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet’s marriage, learn of the entailment, and understand Mrs. Bennet’s goal: to marry off her daughters so they don’t die in poverty.

The Inciting Incident

I wrote extensively about inciting incidents in lesson #3, but to recap, an inciting incident is what sets the plot in motion, changing things for the character and starting them on both their internal and external journey.

In Pride and Prejudice, the inciting incident is Mr. Bingley’s arrival. Mrs. Bennet sets her sights on him marrying her eldest daughter, Jane, which becomes one of the major threads of the novel. Mr. Bingley also brings with him his sisters and his good friend Mr. Darcy. Mr. Darcy quickly becomes antagonistic to our protagonist, Elizabeth, and it is these two characters, their pride and their prejudice, and of course, their romance, that creates the main journey of the novel.

Rising Action Part 1

After the inciting incident comes the rising action of the novel. To use Aristotle’s term, this is the “complication.” This is the middle, with all the interesting scenes and incidents and relationships that help and hinder the characters.

In the first half of this rising action, we get some of the most memorable scenes of Pride and Prejudice: two balls, the introduction of Mr. George Wickham, Mr. Collins and his terrible proposal, and Elizabeth’s trip to Rosings. Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy’s relationship changes and develops, circumstances change for many of the other characters, and the themes of the novel are explored and developed.

The Midpoint

Freytag doesn’t talk about the midpoint in his model, but many of the other structures do, because it’s a very powerful turning point that is used in a majority of stories.

The midpoint is an event in which the core aspects of the character’s journey are brought under a lens. The character typically experiences either a major victory, or a major defeat. This moment will provide the tools the main character needs to make it through the climax and falling action—if she chooses to use them.

The midpoint in Pride and Prejudice is Mr. Darcy’s first proposal to Elizabeth. Both Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth display their pride and prejudice in full force. Mr. Darcy tells Elizabeth all the many reasons he has resisted proposing to her (her family, their lack of connections, and their behavior). Elizabeth refuses him. She verbally attacks him for his pride, and she accuses him of splitting up Mr. Bingley and Jane and of ruining Mr. Wickham’s life forever (a falsehood, which shows the pitfalls of Elizabeth’s prejudice).

This moment marks a major shift for the characters, a moment where they begin to change both internally and externally. (Later, Mr. Darcy explains, “I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle. As a child I was taught what was right, but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit.”) After Elizabeth’s refusal, Mr. Darcy begins to treat others with more kindness; Elizabeth begins to question her preconceived notions and opens herself up to forgiveness and new perspectives.

There are several Pride and Prejudice adaptations that structurally move Darcy’s first proposal to the climax location of the story, which often leads to substantive plot and character changes, because then everything after that is falling action. (An example of this is Kate Hamill’s play adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.) However, in the original text, Mr. Darcy’s first proposal happens almost exactly at the midpoint of the novel, and many film adaptations follow suit (for instance, in the 1995 BBC adaptation, the proposal happens at the very end of the third episode, with three episodes remaining for the rest of the rising action, the falling action, and the denouement).

Rising Action Part 2

After the midpoint, we have more rising action, but as Blake Snyder explains in the screenwriting book Save the Cat, it’s not just fun and games anymore. The stakes are higher and more personal for the characters.

Darcy writes a letter explaining his story to Elizabeth, and Elizabeth reads it and realizes how very wrong she has been. The novel contains several chapters of reflection and soul-searching on her part. Elizabeth returns to her home and makes the decision not to expose Wickham’s true character. She then takes a trip to Derbyshire with her aunt and uncle, and while there they visit Darcy’s home, Pemberley, thinking he is not home. Darcy’s servants testify of his true character, and then Darcy appears. He has changed—he goes out of his way to be friendly and polite to Elizabeth’s aunt and uncle.

The Climax

The climax is the point where all the themes and conflicts of the novel come to a crisis, and where it seems impossible for the characters to get what they want.

In Pride and Prejudice, the climax is when Elizabeth receives Jane’s letter and finds out that her youngest sister, Lydia, has ran off with Mr. Wickham. This truly is a crisis: the whole family will likely be ruined when word of this gets out, and Elizabeth will have no chance of a good marriage. Further, she believes that now Mr. Darcy must despise her—everything he disliked about her family before pales in comparison to this. Mr. Darcy immediately leaves, and Elizabeth is certain that she will never see him again.

Falling Action

The falling action, or what Aristotle called the unravelling, is when all the final problems are addressed. Now the characters are really put to the test: will they be able to use what they learned from the midpoint to conquer the crisis?

In some genres, this would be the big final battle; a Jane Austen story may not have an actual battle, but the stakes are just as high, and the circumstances challenge the characters to their limits.

In Pride and Prejudice, Darcy proves himself in the falling action by finding Lydia and Wickham, forcing them to marry, and providing them with financial support—all without taking any credit for it.

Elizabeth goes home and provides endless support for her family members. Then, when Lady Catherine de Bourgh visits in an attempt to intimidate Elizabeth into submission (and into promising never to enter into an engagement with Mr. Darcy), Elizabeth uses her pride in a useful way, to defend herself and stick to her principles. This event ultimately leads Darcy to realize that he still has a chance with Elizabeth.

The last test of their characters is if Elizabeth and Darcy can let go of their pride one last time and be fully reconciled to each other.

Resolution and Denouement

The resolution of the plot is the final event or moment that resolves or solves the final, major questions that have been raised. The denouement ties up loose ends, and the main characters end up better off than they were at the start of the novel.

Elizabeth and Darcy are able to converse earnestly and deeply, and Darcy proposes. This proposal, and Elizabeth’s acceptance, contrasts strongly with the original proposal: they have let go of their prejudices and made themselves vulnerable to each other.

The denouement consists of two sets of marriages: Jane to Bingley, and Elizabeth to Darcy. Other minor things are wrapped up: Kitty, we find, becomes “less irritable, less ignorant, and less insipid.” Lady Catherine is “indignant,” but ultimately “[condescends] to wait on them at Pemberley.”

On Tragedy

In the Aristotelian tradition, there are only two genres: tragedy and comedy. Anything that is not tragedy is a comedy using this model. Sarah Emsley has made the argument that Austen’s Mansfield Park is a tragedy rather than a comedy, something that will be discussed in more detail in a future lesson.

In a tragedy, the climax is often a high point rather than a crisis. The main character does not learn the lessons they needed to learn: their character does not shift and grow, which leads, in the falling action, to their literal fall. In the denouement, we see their ruin: the main character is worse off than they were at the beginning of the story.

In Sum

The rising action, the sense of building, engages the reader. We become more and more invested in the story, and as a result, the falling action leaves us feeling satisfied. The characters’ internal journeys and growth are interwoven with the main points of the plot structure.

As a disclaimer, many short stories and some novels do not use this structure. Yet even though this plot structure is not universally used, it’s a useful construct that helps us understand what readers expect from stories and an approach that typically is effective at creating an external journey for the main character.

Exercise 1:

Reread one of your favorite books or rewatch one of your favorite films, this time paying attention to structure. Plot the major events on a Freytag Pyramid, and, if possible, include the page number or number of minutes into the film where these events occur within the story. (This is an exercise I have done a number of times, and it’s a really useful way to internalize plot structure.)

Exercise 2:

Take something that happened during your day, some sort of incident, positive or negative. This could be an interaction at work, the process of cooking something, a conversation with a child, etc. Write this as a short story (maximum three paragraphs) with a beginning, middle, and end. Make sure to include an inciting incident, rising action, a midpoint, some sort of crisis, and then falling action/resolution. Then go back and label the parts by adding brackets with descriptions such as [Inciting Incident]. If you’d like, share the story in the comments!

Exercise 3:

Option 1: Outline a story idea using Freytag’s pyramid. You don’t need to include all the elements of the story, but make sure to include the key details.

Option 2: If you prefer discovery writing to outlining, brainstorm the elements you would like both the climax and falling action to include (i.e. something very romantic, a big twist, something action packed, etc.).

Option 3: If you already have a full draft of a novel, use Freytag’s pyramid as a revision tool. Write the major plot points you’ve included on the pyramid, and list the page numbers where these events occur in your manuscript. To take it up a notch, write down the character’s emotions and/or internal struggle at each of these key events.

Now analyze your pyramid:

- Are there any events that would be more effective if moved to a different part of the pyramid?

- Does the main character face enough struggle?

- At the crisis, have you successfully put the main character in a spot where it seems impossible for them to succeed?

- Does the main character use what they have learned during the rising action to solve their problems during the falling action?