Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#11: Use Exposition to Set the Stage

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

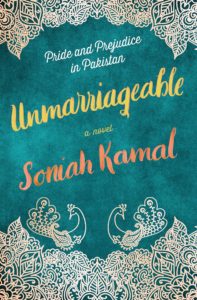

Soniah Kamal’s novel Unmarriageable, an incredible retelling of Pride and Prejudice in modern-day Pakistan, opens with Alysba Binat (our Elizabeth counterpart) teaching Pride and Prejudice at an English-speaking high school in Pakistan. In the beginning scene, she has her students—all female—write their own first lines inspired by the first line of Pride and Prejudice, their own “truths universally acknowledged.” As Alys leads the discussion, she brings up double-standards for men and women, explains that women’s independence is not a Western idea and has roots in their own culture, and raises the possibility that a woman’s sole purpose is not to marry and have children.

One of the ninth graders arrives late to class, a diamond engagement ring on her hand, and eventually the students turn the questions to Alys—why are you not married?

“Unfortunately, I don’t think any man I’ve met is my equal, and neither, I fear, is any man likely to think I’m his. So, no marriage for me.”

This scene sets up the core conflict of the novel—will Alys find her equal and eventually marry? It also sets up Alys’ personality, her quest to educate the young women of her community, and the cultural context in which she lives. In the first two chapters we also learn of her conflicts with the principal, information about her four sisters, how the family has lost their fortune and gotten into the financial straits that require the two oldest sisters to work, and we get a sense of the city and where it’s wealth and poverty are located. All this is so the stage is set, so that when the inciting incident disrupts Alys’ life and moves her on her journey (in the form of an invitation to a huge wedding where they will meet Bingla and Darsee), we as an audience are ready for it.

This is exposition, the setting of the stage for the story in order to provide important background information to the reader about the characters, their history, and their world.

As discussed in the lesson on plot structure and external journeys, the exposition shows the world in stasis, and it requires the inciting incident to launch the external journey of the plot and the internal journey of character transformation.

According to Oxford Languages, the word exposition comes from the Latin verb exponere, which means to “expose, publish, [and] explain.”

exponere = to expose, to publish, to explain

Good exposition should:

Give us an understanding of the main character, and possibly of other characters

Present key details from the character’s past and history

Provide enough worldbuilding (details about the world in which the character lives, and how it functions) to orient the reader

Focus on details that will demonstrate the disruptiveness of the inciting incident

Subtly raise themes and issues which will explored throughout the story

The first four paragraphs of Jane Austen’s novel Emma provide the exposition for the story. We begin with the opening line:

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

This quickly paints an image of Emma’s character, her high place in society, and her general satisfaction with life.

In the second paragraph we learn the following, which brings up key details from Emma’s past and sets up the world and her place in it:

- Emma is the second daughter

- Her sister is married and gone

- She is mistress of the house (or basically, the female manager of it)

- Her father is “affectionate” and “indulgent”

- Her mother died when she was very young

- Her governess acted as a replacement mother figure in her life

That’s a lot for one two-sentence paragraph: Jane Austen manages to swiftly set the stage.

The third paragraph goes into more details on the governess, Miss Taylor, because these details will demonstrate the disruptiveness of the inciting incident:

- Miss Taylor has been with the family for 16 years

- She is more of a friend or sister figure than a governess

- She does not restrain or direct Emma (and has not for quite some time)

- “They had been living together as friend and friend very mutually attached, and Emma doing just what she liked; highly esteeming Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by her own.”

The fourth paragraph raises the themes and issues which will be explored throughout the story. In this case, it’s a look at the flaws in Emma’s character, and how these flaws will drive the narrative:

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself: these were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at present so unperceived, that they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.

By the time we reach the fifth paragraph, all the essential details have been explained, and we are prepared for the inciting incident: Miss Taylor’s marriage.

We learn plenty of other details of backstory as the novel progresses—details about the past and about Emma’s relationships with others in her community—but these are not included in the initial exposition, because they are not essential for setting the stage.

Sometimes exposition—this setting of the stage for the reader—takes several chapters, as in the example of Unmarriageable. Other times, it takes a few paragraphs, such as in Emma. The next lesson will discuss stories that start in medias res, at the moment of the inciting incident, or sometimes even after the inciting incident, and address how exposition can be incorporated in small amounts as the story progresses.

Regardless of the manner in which the exposition is presented, it sets the stage for the story and orients the reader.

Exercise 1: In the beginning of Emma, Jane Austen uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. She sets forth the character, the world, and the situation through the perspective of a storyteller introducing her cast. The narrator is insightful and interesting, and is unafraid to comment on her characters and their attributes.

Brainstorm a new character by choosing and name and writing down three of their defining characteristics, attributes, or interests.

Set a timer for 15 minutes, and draft a brief exposition which uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. This should set the stage for the character and their world.

Exercise 2: In Unmarriageable, Soniah Kamal uses a close third person point of view. She includes the same sort of expository details as Austen does in Emma, but she reveals them through use of a scene. (Jane Austen does uses this approach—providing exposition through a scene—in some of her novels.)

Use the same character and characteristics/attributes/interests from exercise 1. Instead of sharing these details from a storyteller perspective, figure out how to reveal these details organically through a scene—have these demonstrated through the character’s actions or interactions. Set a timer for 15 minutes and write an opening scene that provides exposition.

Note: providing exposition through a scene is currently the most common approach in writing, though there are books still being published that open with the perspective of a storyteller setting the stage.)

Exercise 3:

Option 1: For a new story, brainstorm elements that may be useful for include in the exposition.

- Who is the main character?

- What about the character’s past informs who they are today?

- Who are the other key characters?

- What do readers need to understand about the world?

- What themes or issues could be raised that will be explored throughout the story?

- What details about the character and the world could be included in the exposition that will contrast and show the disruptiveness of the inciting incident?

Once you have brainstormed, consider what absolutely must be revealed in the exposition, and what can be revealed later. Most details about the character and the world can be revealed, piece by piece, later in the story, so choose what is both the most essential and the most interesting way to take us into the world and the perspective of the main character.

Option 2:

If you have already drafted a story, analyze what you included as part of the exposition. Label each detail with categories that could include things like “character attribute,” “character history,” “supporting character,” “relationship,” “worldbuilding,” “theme,” etc. Are there any details that could be saved for later in the story? Are any details that are missing that would demonstrate how the character’s world is disrupted by the inciting incident?

#10: Use a Reader-Writer Contract to Create a Satisfying Resolution

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

Andrew Davies’ Sanditon, a recent TV adaptation of Jane Austen’s uncompleted novel, aired in 2019 in the UK and 2020 in the US. It has been rather polarizing for viewers (the Twitter and Facebook arguments have been heated!). Among those who finished the series, there have been two major reactions: the first group is disappointed by the final episode, and the second group is ravenous for a second season. (Personally, I would love a second season—#SaveSandition.)

What unites both groups is a sense that the promises made at the beginning of the show have not yet been fulfilled. Whether that leads to disappointment or a desire for more so that the promises can be fulfilled (a Jane Austen heroine always gets her man!), it teaches an important principle of writing:

Audiences have expectations about what makes a satisfying conclusion or resolution for any given story, and these expectations are based on implied promises made by the writers of stories.

Note: many of these expectations are based on the standard plot structure discussed in Jane Austen Writing Lesson #4.

The Reader-Writer Contract

I first learned about the reader-writer contract in an introduction to film class that I took my freshman year of college. The principles, though, apply just as well to literature as to film.

The reader-writer contract is an agreement between the reader and the writer of a text.

The reader promises to suspend disbelief and invest their time and attention in the story. (Sometimes, the reader also makes a financial investment.)

The writer promises to weave an engaging, entertaining story that delivers on commitments made at the beginning of the story, including, but not limited to:

- Genre

- Plot

- Character

- Style

- Point of View

The Reader-Writer Contract of Jane Austen’s “A History of England”

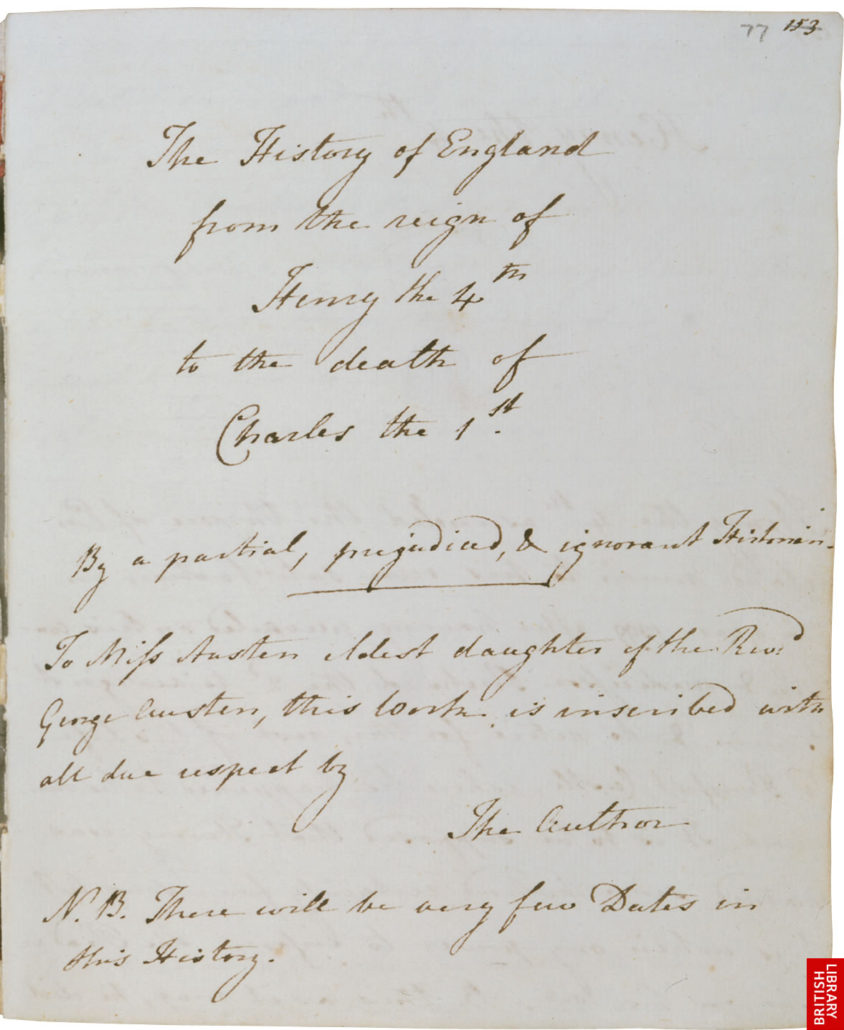

When Jane Austen was sixteen years old, she wrote a short nonfiction text called “The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the Death of Charles the 1st.” You can read it online or in book form. She did not write it with the intent of publishing it: like much of her juvenilia (her works written as a child/teen), the intent was to share and perform it with her family. “The History of England” was written in November 1791, when she was not quite sixteen years old.

We’ll examine the beginning of “The History of England,” consider how the reader-writer contract sets up its promises, and then look at how these promises are fulfilled to create a satisfying resolution.

The Title and Byline

The title page Jane Austen wrote by hand for “The History of England” (she copied this into her second notebook of writings from her youth, which can be viewed online at The British Library).

The full title of the piece is “The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the death of Charles the 1st.” This is a very standard title for a serious history written in the 1790s. Of course, immediately after the title comes the byline:

By a partial, prejudiced, and ignorant Historian.

Before the piece begins, we also receive this note:

N.B. There will be very few dates in this history.

Already, Austen has established genre expectations and tone: this is a parody of standard histories. This is not a text we should turn if we truly want to learn about British history. The admission that the historian author is “partial, prejudiced, and ignorant” is clever and immediately attracts us to the speaker—despite her alleged ignorance, we immediately want to know what she has to say.

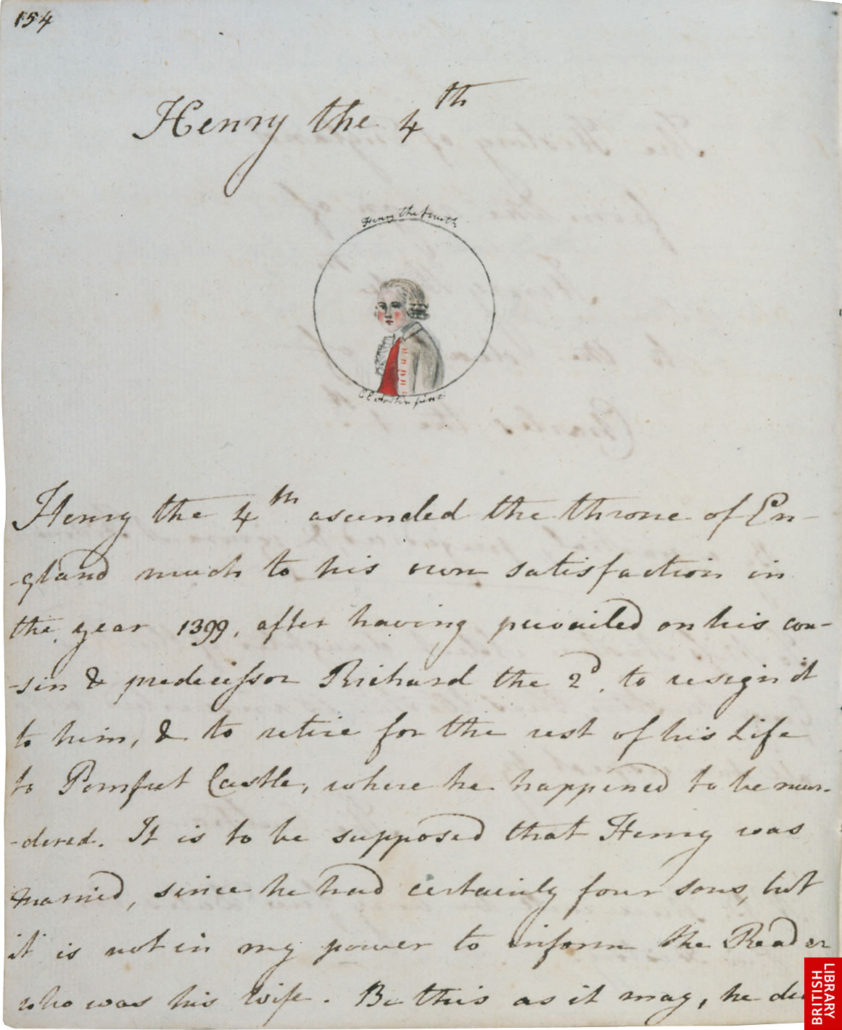

The First Paragraph

Another handwritten page by Jane Austen, from The British Library.

Jane Austen continues to establish the reader-writer contract in the first paragraph:

Henry the 4th ascended the throne of England much to his own satisfaction in the year 1399, after having prevailed on his cousin & predecessor Richard the 2d to resign it to him, & to retire for the rest of his Life to Pomfret Castle, where he happened to be murdered. It is to be supposed that Henry was married, since he had certainly four sons, but it is not in my power to inform the Reader who was his wife. Be this as it may, he did not live for ever, but falling ill, his son the Prince of Wales came and took away the crown; whereupon, the King made a long speech, for which I must refer the Reader to Shakespeare’s Plays, & the Prince made a still longer. Things being thus settled between them the King died, & was succeeded by his son Henry who had previously beat Sir William Gascoigne.

This firmly establishes the point of view of the speaker, her (intentionally) biased relationship with the subject matter, and the humor created as a result.

Promises Made and Kept

Swiftly, in the beginning of the piece, our expectations have been set, and the reader-writer contract has been forged. Here are a few of the promises that have been made:

- Genre: Parody/satire, with the effect of creating humor and commentary, both on these figures in history, and on the persona of a historian

- Plot: marriages, deaths, killings, and random details about a series of rulers from Henry the 4th to Charles the 1st.

- Character: the characters of the past are set forth, but the narrator herself seems to be a character

- Style: playful, amusing

- Point of view: first person, ignorant “historian” (not simply a reader, but someone making a claim that despite their ignorance, they still deserve the title “historian”)

These promises, having been made at the start, are kept and built upon throughout the piece.

A few of my favorite lines demonstrate this quite well:

“This unfortunate Prince lived so little a while that nobody had time to draw his picture.”

“Tho’ inferior to her lovely Cousin the Queen of Scots, [she] was yet an amiable young woman & famous for reading Greek while other people were hunting.”

“He was beheaded, of which he might with reason have been proud, had he known that such was the death of Mary Queen of Scotland; but as it was impossible that he should be conscious of what had never happened, it does not appear that he felt particularly delighted with the manner of it.”

The Satisfying Conclusion relies on these initial promises

In order for the conclusion of a story to be satisfying, it must fulfill the promises that it has made.

The following is the final paragraph of Jane Austen’s “History”:

The Events of this Monarch’s reign are too numerous for my pen, and indeed the recital of any Events (except what I make myself) is uninteresting to me; my principal reason for undertaking the History of England being to prove the innocence of the Queen of Scotland, which I flatter myself with having effectually done, and to abuse Elizabeth, tho’ I am rather fearful of having fallen short in the latter part of my Scheme. —. As therefore it is not my intention to give any particular account of the distresses into which this King was involved through the misconduct & Cruelty of his Parliament, I shall satisfy myself with vindicating him from the Reproach of arbitrary & tyrannical Government with which he has often been charged. This, I feel, is not difficult to be done, for with one argument I am certain of satisfying every sensible & well disposed person whose opinions have been properly guided by a good Education — & this argument is that he was a Stuart.

Austen maintains the genre, tone, point of view, etc., but she goes further: she takes the parody to its satisfying conclusion by throwing aside the cloak of a historian’s supposed neutrality, directly stating her skewed intentions, and closing with an unsupported, fallacious argument.

In Conclusion

Typically, the Reader-Writer contract should be established within the first 10-20% of a story. We need buy-in and commitment from our readers.

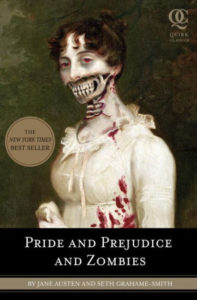

If you went to the movie theater to watch a romantic comedy and half-way through it transformed into a zombie film, you would probably walk out, unless there had been clues planted at the beginning of the film that a zombie film was coming.

Notice that the novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies begins to establish the contract of a not-so-traditional Jane Austen story through the cover and the opening line:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a zombie in possession of brains must be in want of more brains.”

While the contract should be established quickly, this doesn’t mean you have to give everything away at the beginning of the story. There can be plenty of twists and turns, grand reveals and surprises, new characters and subplots—in fact, readers expect these. But if there is a large shift, hints of it must be sprinkled near the beginning. And most importantly, to create a satisfying resolution at the end of the story, the resolution must fulfill the promises set up at the beginning of the story.

It’s like ordering at a restaurant. If you order a vegetarian meal, the meal better not have chicken in it. It’s fine to defy expectations, push genre limits, experiment and break rules, but you must be aware of the contract you are establishing with the reader, and if you want a satisfying conclusion, you must find a way to keep that contract.

Exercise 1: Choose a book, film, or TV show that you have never read or watched before—this should be new for you. Now read or watch the first 10% of the book/film/first episode.

Before you read or watch more, try to figure out the reader-writer contract for this story.

- What promises has the writer made?

- What is the genre, and how does the story treat the genre? (firmly in genre, parodying the genre, mix of two genres, etc.)

- What expectations do you have for plot and character?

- What is the point of view? What is the writer’s style?

Read or watch the rest of the story, and then evaluate how it met your expectations. Was the reader-writer contract kept? Was the story effective for you as a reader/viewer? Did anything defy what was established in the reader-writer contract, and if so, was it effective?

Exercise 2: Create a template Reader-Writer Contract that works for an entire category, genre, or subgenre of writing. Make sure that this category, genre, or subgenre is one that you write or would like to write.

Sample categories:

- Literary

- Genre fiction

- Poetry

- Creative nonfiction

Sample genres:

- Romance

- Science fiction

- Mystery

- Thriller

- Cooking

- Biography

Sample subgenres:

- Regency romance

- Urban fantasy

- Bildungsroman

- Popular history

- True crime

Once you have chosen a category, genre, or subgenre, make a reader-writer’s contract. Consider standard characteristics, plot expectations (some categories/genres have very fixed expectations for plot events, while the expectations are more loose for others), character, style, point of view, and anything else that might make up part of a standard reader-writer contract for this category/genre/subgenre.

Exercise 3: We expect large promises to be fulfilled—if the story is a romance, the main couple should be together by the end of the story. As readers and viewers, we also love it when small promises are fulfilled. If the character is searching for a good taco several times throughout the story, it’s going to be really satisfying if they get that good taco by the end of the story.

Consider one of your own stories, that you have either drafted or are currently planning.

What are tiny promises that either have been made or could be made near the beginning of the novel? (Think “good taco” level promises—this could be something related to the main character, a minor character, etc.)

How and where could these promises be fulfilled?