Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#15: Make Your Character Need Something

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

In the very first Jane Austen Writing Lesson, I talked about how a character must want something. This drives the forward movement of the novel.

Yet in addition to wants, characters also have needs.

In the novel Emma, Emma Woodhouse wants to be a matchmaker, and she wants to exert her control on the community. This is her conscious desire.

Yet Emma is coming from a place of loss—she has lost her dear governess to marriage, previously, she lost her mother to death and her older sister to marriage, and now she is alone, with a perpetually-ill father.

What Emma really needs is friendship and connection. Despite being one of the richest members of her community, she desperately needs to feel like she is important and of value.

All characters have conscious wants and needs, things they are actively seeking for. But they also have underlying wants and needs, which are often subconscious. They may not be aware of these needs, but they still drive the character’s behavior.

Gif of Harriet Smith and Emma Woodhouse from the 2020 film Emma.

Early in the novel, Emma befriends Harriet Smith and immediately plans a match for her: to Mr. Elton.

But then Mr. Martin, a farmer, proposes to Harriet.

On the surface level, if Harriet accepts Mr. Martin’s proposal, Emma fails at getting what she wants: her matchmaking will have gone to naught.

But it is not just Emma’s overlying want that is threatened, but also her underlying needs, and we see this play out in the scene in which Emma, very manipulatively, encourages Harriet to refuse Mr. Martin’s proposal. When Harriet begins to come to the conclusion that she should reject Mr. Martin, Emma uses all her rhetorical powers to reinforce it.

At last, with some hesitation, Harriet said—

“Miss Woodhouse, as you will not give me your opinion, I must do as well as I can by myself; and I have now quite determined, and really almost made up my mind—to refuse Mr. Martin. Do you think I am right?”

“Perfectly, perfectly right, my dearest Harriet; you are doing just what you ought. While you were all in suspense I kept my feelings to myself, but now that you are so completely decided I have no hesitation in approving. Dear Harriet, I give myself joy of this. It would have grieved me to lose your acquaintance, which must have been the consequence of your marrying Mr. Martin. While you were in the smallest degree wavering, I said nothing about it, because I would not influence; but it would have been the loss of a friend to me. I could not have visited Mrs. Robert Martin, of Abbey-Mill Farm. Now I am secure of you for ever.”

Harriet had not surmised her own danger, but the idea of it struck her forcibly.

Emma’s need for friendship, connection, and self-importance drive this scene as much as her desire to be matchmaker.

As you construct characters, make sure they want something, but also make sure that they have deeper, underlying needs.

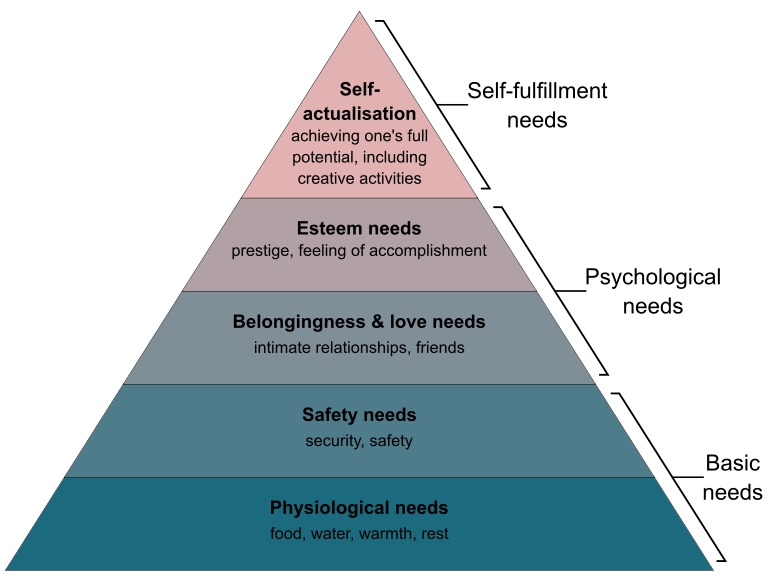

One way to think about character needs is through the lens of psychology. Abraham Maslow wrote about a hierarchy of needs, and any of these intrinsic human needs can be a need for a story character.

Near the bottom of his pyramid are needs for basic survival—food, water, sleep, shelter, safety, and financial security. Further up the pyramid are needs related to love and belonging, whether that’s a sense of connection or friendship, true intimacy or family, or being a true part of community. Then Maslow talks about esteem—this could be respect from others, self-respect and self-esteem, public recognition for one’s accomplishments, or a feeling of strength and wholeness. At the top of the pyramid is self-actualization—becoming one’s fullest self and achieving one’s potential.

Image by Androidmarsexpress, Creative Commons license

Typically, you want to choose one or two overarching needs which drive your character. These needs may conscious or subconscious, or a need may start as subconscious and the character may become aware of it throughout the story.

Other smaller wants and needs may be manifest in individual scenes and interactions with other characters, but if your main character has a core want and a core need, then this will shape the overall arc of the story, both in terms of their external journey and their internal journey.

Exercise 1: Teresa wants to win this year’s chili cook-off. This is her driving want throughout a story. But what does she need? Choose one of the needs from Maslow’s hierarchy. Is she trying to get recognition—and if so, why? Does she need acceptance, friendship, love? Will the prize money help her pay her rent?

Once you have chosen a need, write a short scene—probably 2 or 3 paragraphs—in which both Teresa’s want and need inform her actions, dialogue, and thoughts. This scene could be when she signs up for the chili cook-off, when she’s buying ingredients, as she’s cooking, during the judging—any scene, because both her want and her need should subtly inform her.

(Note: self-actualization is a really difficult need to write, and most of the time, we don’t hit the self-actualization stage unless all of our other needs have been met, so it’s often better to choose a different need for our characters.)

Exercise 2: Choose one of your favorite books or films. What is the main character’s driving want in the story? What is the main character’s driving need in the story? How do the want and the need interact with each other—does the quest for one ever interfere with the quest for the other? Does the want or the need shift over time? If you would like, in the comments share the title of the story, and the character’s want and need.

Exercise 3: Take a scene that you have written and analyze it for character wants and needs. Use one color to highlight lines or phrases that relate to the character’s want(s), and another color to highlight lines or phrases that relate to the character’s need(s). Some lines may be highlighted by both colors. How could you revise the scene with wants and needs in mind?

#14: Incorporate Backstory Strategically

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

What is backstory?

Backstory is history and information about what happens before the story. Backstory is typically related to the characters, the situation, and the world in which they live.

Most backstory is never mentioned in a story—there are thousands of details and past events that inform the character and their community, thousands of excess details that your readers don’t want or need to know.

Yet there are plenty of details which the reader does need. The key is deciding how to share them.

One of the primary purposes of exposition is to provide backstory, yet too much backstory weighs down the exposition. Anytime you dive into past events, situations, details, and information, there’s a risk of creating an infodump.

An infodump is an excess of information that pulls us out of the narrative. Information is piled on the reader, who does not have direction, and who doesn’t feel any sense of connection to the information. When too much of this sort of information is given to the reader at once, none of the information has purpose or weight, and the reader often loses interest in the story.

Instead of creating a pile of information, consider the individual pieces, and how they could be incorporated. The soda can in this beach pile might not feel like garbage if we encounter it by itself, as we’re walking along the beach. We might see someone drinking it—it might bring up an interesting recollection of a past event or situation.

The author Jo Walton talks about the benefits of what she calls incluing, or “the process of scattering information seamlessly through the text, as opposed to stopping the story to impart the information.”

Backstory should be woven not just through the exposition of a story, but throughout the entire story.

Weaving in Backstory in Persuasion

In the exposition of Persuasion, Jane Austen establishes the Elliot family, the death of Lady Elliot, and the characters of the three daughters, including the oft overlooked Anne Elliot.

The heart of Persuasion is about Anne Elliot and her relationships, in particular her relationship with Captain Wentworth. Yet the crucial backstory about the relationship between them is not provided in the exposition of the novel, but is carefully woven throughout.

The Elliots have decided that in order to remain financially solvent, they must rent out their home, Kellynch Hall. In chapter 3, they discuss a possible tenant: Admiral Croft.

One line of dialogue gives us Anne’s viewpoint on the Navy:

“The navy, I think, who have done so much for us, have at least an equal claim with any other set of men, for all the comforts and all the privileges which any home can give.”

This is subtle backstory—it’s something she is saying in the moment, in response to her father’s prejudice. Yet it reveals her attitude towards those who serve in the Navy.

A few pages later, Anne is able to give specific details on what Admiral Croft is known for—that he fought in Trafalgar and has been stationed in the East Indies. Once again, this provides key backstory. As readers, we’ve learned that Anne knows much more about the Crofts than anyone in her family, yet we don’t yet know how she learned this information.

A few pages later, someone mentions that years back, someone had visited that had some connection to Admiral Croft, and after a pause, Anne volunteers a single detail.

“You mean Mr. Wentworth, I suppose,” said Anne.

Her hesitation, the lack of detail that she gives, all reveal things about Anne and her relationship with this family.

By the end of chapter 3 , Sir Walter Elliot decides that he will allow Admiral Croft to rent the estate. The chapter ends with this sentence.

No sooner had such an end been reached, than Anne, who had been a most attentive listener to the whole, left the room, to seek the comfort of cool air for her flushed cheeks; and as she walked along a favourite grove, said, with a gentle sigh, “a few months more, and he, perhaps, may be walking here.”

In this moment, we see Anne’s current emotions and thoughts, but backstory is also revealed: we are given a sense of love lost, and we see the agitation this creates for Anne.

Throughout this chapter, there have been plenty of opportunities where Jane Austen could have provided an infodump, even spots where it might be natural and not feel like an infodump. Yet by spreading the information, piece by piece, it allows the scene to build, it provokes our curiosity, it gives crucial insight into Anne’s character, and it prepares us for chapter four, when we are given a larger amount of backstory.

The first line of Chapter 4:

He was not Mr. Wentworth, the former curate of Monkford, however suspicious appearances may be, but a captain Frederick Wentworth, his brother.

The narrator then describes Captain Wentworth’s situation years before, and how he and Anne met and fell in love. It tells us of their short engagement, and how Sir Walter and Lady Russell had convinced Anne to break it off.

This is a lot of backstory, but by this point, we care about Anne and this backstory has meaning for us as readers.

A gif from the 2007 film version of Persuasion: Anne and Captain Wentworth

Incorporating Information on a Need to Know Basis

Backstory is something that I often don’t get quite right in a first draft—it’s something I finesse during revision. But how do you do it? How do you weave it?

What Jane Austen often does is provide enough context ahead of time so the reader is oriented, and then adds information and backstory as the character interacts with present, current things.

For example, Uppercross is mentioned as the residence of Anne’s older sister, Mary. Mary invites Anne to go to Uppercross and she agrees. That’s our context. That’s what’s going to keep us oriented.

A few pages later, Anne goes to stay at Uppercross. Now, as she’s arriving at Uppercross, we receive a brief description of the village.

More details are given on a need-to-know basis, as they provide context, unravel character, forward the plot, and provide insights into the emotions of the characters:

Here Anne had often been staying. She knew the ways of Uppercross as well as those of Kellynch. The two families were so continually meetings, so much in the habit of running in and out of each other’s house at all hours, that it was rather a surprise to her to find Mary alone…

Here, we receive backstory on Mary’s strong connection to Uppercross. We see how familiar she is with it. And we experience this as she enters the cottage and finds her sister (surprisingly) alone.

Using Backstory to Build Moments of Emotional Impact

Backstory can also build to moments of emotional impact.

Captain Wentworth comes to Uppercross, and soon becomes friends with Anne’s host, which means that Wentworth and Anne must interact frequently.

They had no conversation together, no intercourse but what the commonest civility required. Once so much to each other! Now nothing! There had been a time, when of all the large party now filling the drawing-room at Uppercross, they would have found it most difficult to cease to speak to one another. With the exception, perhaps, of Admiral and Mrs. Croft, who seemed particularly attached and happy, (Anne could allow no other exception even among the married couples) there could have been no two hearts so open, no tastes so similar, no feelings so in unison, no countenances so beloved. Now they were as strangers; nay, worse than strangers, for the could never become acquainted. It was a perpetual estrangement.

This is a powerful, emotional moment of backstory, in which it is revealed how similar Anne and Wentworth were to each other, and how perfectly suited they had been for each other: “there could have been no two hearts so open.” Their similarity and how well suited they are for each other could have been revealed at many points of backstory prior to this, but instead, this bit of backstory is foreshadowed and saved for this moment, when it can have the greatest emotional impact because it is placed in contrast with Anne and Wentworth’s current relationship.

When you are using backstory for large emotional impact, limit the amount of backstory used. If we didn’t find out until now that Anne and Wentworth had been engaged, and then, at this moment, we found out they had been engaged and that they had been perfectly suited, this scene would be bogged down in the amount of impact, readers would be focusing on the new knowledge that they had a broken engagement, and their similarity would no longer have the space to have the same emotional impact.

When I’m editing and I see a scene where backstory is supposed to create emotional impact, I often realize that I’ve saved too much backstory for these scene, and I have to find pieces of backstory that I can weave in earlier so they aren’t distracting the reader from the true purpose and weight of the scene.

In Conclusion

Backstory should be included not only in the exposition, but throughout the entire novel. The incorporation of backstory is particularly suited to written fiction—it is much more difficult to include in film or theatre—and it provides insight into the character’s mind, perspective, experience, and emotions.

Exercise 1: Read the following paragraph.

Sandra stood at the edge of the dock, staring into the water. She could hear the other teenagers behind her, their laughter, their utter unconcern, as if this meant nothing. This meant nothing to them. They didn’t fear the water. She dipped her toe into the lake. She would be fine. She could do this. She closed her eyes, sucked in a breath of air and courage, and jumped.

Rewrite the paragraph, and as you do so, include 1 or 2 pieces of backstory.

This backstory could be about why Sandra fears water, what happened the last time she was in the water, or what happened to someone she knows, or it could be about the troubled history of this lake, a memory from this particular spot, etc. The type of information you choose to include will impact the emotion and direction of the paragraph.

Exercise 2: Take a novel that you have read at least once before. Skip the exposition, and now skim at least two or three chapters, looking for moments of backstory. Use post-it notes to mark these moments of backstory. Now analyze the author’s use of backstory:

- When is backstory incorporated?

- How is backstory incorporated?

- Are there moments where backstory is used to create emotional impact?

Exercise 3:

Take a story you have written and choose a key emotional moment that doesn’t include any backstory. Revise the scene to incorporate an element of backstory—small or large—in a way that increases the emotional impact of the moment.