Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#17: Make Your Characters Active

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

In 2012 I created a daily video blog, where every single day I posted a five to thirty second video of something interesting. As I worked on this project, I discovered that only certain categories of things would work for the project:

- A still shot (the camera not moving) with something moving inside the frame

- A moving shot (the camera moving) with something moving inside the frame

- A moving shot (the camera moving) with still objects

The only other option—a still shot with nothing moving—was not actually an option. Because that would be a photograph, not a video.

I quickly discovered that the best videos fit in categories 1 or 2. If something was moving in the frame, it attracted interested, regardless of what I did with the camera. (As a side note, my main claim to internet fame is that Day 119 of my blog—which features a DVD screensaver hitting the corner of the TV screen—has been viewed over 50,000 times.)

Our eyes are drawn immediately to things in motion. Our eyes, and often our hearts. This is the power of using active characters.

Readers are drawn to active characters. Active characters are doing. Outside things may happen to them, but they are not just observers or reactors. They do not let themselves be pushed around or be determined by others. They go, they do, they strive.

Making your protagonist an active character creates a powerful story. This propels them on an external journey, through the plot, with all its outward struggle and growth. It also propels them through an internal journey, facilitating character development, with its inner struggle and growth.

Both of the female leads in Sense and Sensibility—the two oldest Dashwood sisters—are active characters. The eldest sister, Elinor, is active—she steers her mother away from renting too expensive of a house, and she does much to ease the pain of others and make their cottage a home. The middle sister, Marianne, is active in a different direction.

Marianne refuses to let others play matchmaker with her future and is guided by her own opinions and philosophies. (Unlike Elinor, she is unafraid of offending others, and not held back by a strong sense of decorum.) She is energetic, and attempts to find and make beauty in the world.

Their cottage is in a beautiful countryside, and on a somewhat blustery day, Marianne encourages her younger sister Margaret to walk with her:

They gaily ascended the downs, rejoicing in their own penetration at every glimpse of blue sky; and when they caught in their faces the animating gales of a high south-westerly wind, they pitied the fears which had prevented their mother and Elinor from sharing such delightful sensations.

“Is there a felicity in the world,” said Marianne, “superior to this?—Margaret, we will walk here at least two hours.”

Their walk, however, is cut short by the driving rain. Marianne is an active character, in charge of her own destiny, but even she cannot prevent the weather. Yet even in reacting to the weather, she resists passivity:

Chagrined and surprised, they were obliged, though unwillingly, to turn back, for no shelter was nearer than their own house. One consolation however remained for them, to which the exigence of the moment gave more than usual propriety; it was that of running with all possible speed down the steep side of the hill which led immediately to their garden gate.

Marianne is delightful because of her energy, her joyous outlook on life, and her refusal to do things in a simple, boring way.

As a result of her action, she hurts her ankle on the hill, and is rescued by a charming gentleman, Mr. Willoughby, who carries her home.

Over the coming chapters, Marianne becomes quite attached to Willoughby. This worries Elinor, who actively encourages Marianne to be more careful with her affections, particularly with how they might be interpreted by others outside of their family. Marianne actively resists Elinor’s advice, and responds:

“You are mistaken, Elinor,” said she warmly, “in supposing I know very little of Willoughby. I have not known him long indeed, but I am much better acquainted with him, than I am with any other creature in the world, except yourself and mama. It is not time or opportunity that is to determine intimacy;—it is disposition alone. Seven years would be insufficient to make some people acquainted with each other, and seven days are more than enough for others. I should hold myself guilty of greater impropriety in accepting a horse from my brother, than from Willoughby. Of John I know very little, though we have lived together for years; but of Willoughby my judgment has long been formed.”

What are the marks of an active character?

An active character:

Reaches for their goals or wants

Engages in purposeful dialogue that attempts to have impact, persuade, or create change

Takes actions—large or small—with purpose

When reacting to outside events, asserts themselves and does things their own way

An active character can be bold or shy, outspoken or quiet, and their actions can be grand or minute. But something internal propels them forward.

Yet no character is fully active, and as writers, we shouldn’t consider it a dichotomous choice between active and passive characters. No character is active all of the time—nor should they be. This movement along the spectrum of active and passive can be powerful.

Later on in Sense and Sensibility, Marianne falls into a deep depression, and becomes a largely inactive character. Her moments of activity—like taking a walk in bad weather—do her more harm than good. She becomes ill, which forces further inactivity upon her: at this point it is the doctor’s treatment and fate which determine her future.

Yet the fact that Marianne is generally an active character both creates audience investment in her and helps drive the story forward. Then, in these moments of passivity, we still root for her.

Exercise 1: The following passage focuses on a passive character:

“You want vanilla?” asked George.

Rudy nodded at her brother. “Sure.” Vanilla was as good as any other flavor.

George ordered and paid. “My treat,” he said. “It’s been way too long.”

“Thanks,” said Rudy.

The server gave them their ice cream and they sat down to a table.

“How’s work going?” asked Rudy.

He told stories about his adventures as a plumber, and some of the crazy things he learned about people’s personal lives.

“How’s work going for you?” asked George.

“Same as always,” said Rudy.

George’s phone rang. He looked at the screen. “Mind if I take this?”

“Not at all.”

He stepped out of the ice cream shop.

Rudy looked around the restaurant at the happy families, happy couples. There was only one person sitting alone, a man about her age. He made eye contact, and she looked down, pretending she hadn’t noticed.

Rewrite the passage to make Rudy a more active character. You could make her more active throughout, or in just one section of the scene. Also, feel free to take the scene in a different direction.

Exercise 2: Read a book or watch a film and analyze the text for active and passive characters. Who is passive? Who is active? Are there moments when characters become more passive or more active, and what is the result? As you analyze, pay particular attention to the protagonist.

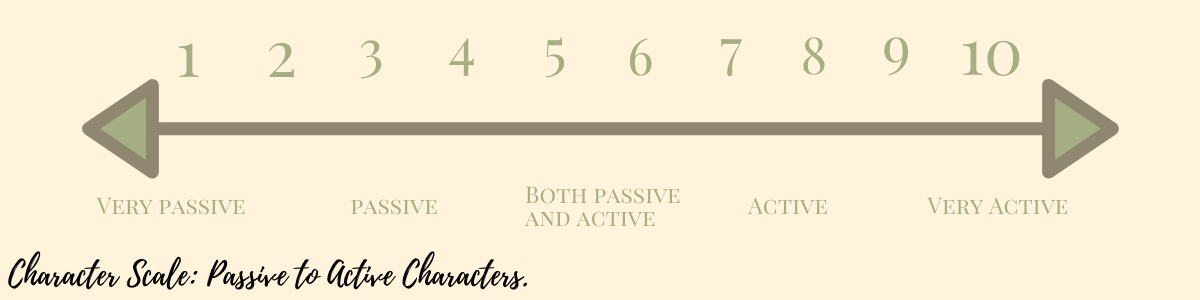

Exercise 3: If you’ve drafted a novel or as short story, analyze each scene/chapter for where your main character falls on the spectrum from active to passive. Assign each scene a number from 1 to 10 on a passive to active scale. For the purposes of this exercise, use 10 to mean a character is extremely active, a 7 or 8 for active, a 5 or 6 for scenes with both active and passive elements, a 3 for passive, and a 1 for extremely passive.

What sort of arc or movement is created by the main character’s movement along the passive-active spectrum? Are there scenes where your character should be more active? Where your character should be more passive? Where your character should be wrestling with both active and passive tendencies in themselves?

#16: Make Your Characters Multifaceted

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

The only time when Mr. Darcy is a flat character is when he is a life-sized cardboard cutout in the film Austenland.

Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth Bennet, and all of Jane Austen’s other main characters are three-dimensional—they feel as if they come to life off of the page.

This is one of those moments that makes me love the film Austenland: in rage, a boyfriend walks out, punching the cardboard Mr. Darcy, which Jane Hayes then fixes. And kisses.

A flat character is simple, uncomplicated, does not change or develop, and is often uninteresting.

A round character, also known as a three-dimensional character, feels like a fully developed real person, with nuance and complexity, and the ability to experience real change and development over the course of a story.

A round or three-dimensional character is what I like to call multifaceted: she has multiple sides, aspects, or features, that fit together to create a character. Yet this is not just a collection of multiple elements squished together: like the facets or sides of a gemstone, these elements have been carefully crafted, cut, and polished.

Let’s look at some of the basic features and characteristics of our two main characters from Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy:

Elizabeth Bennet:

- Plays the pianoforte

- Likes reading

- Likes walking

- Good at dancing

- Clever

- Witty

- Judgmental

- Idealist

- Has many friends

Mr. Darcy:

- Rich

- Good at letter-writing

- Caring brother

- Loyal friend

- Likes reading

- Expects much of others

- Well-spoken

- Proud

- Unforgiving

These attributes, interests, skills, and personality traits are inherently interesting in combination, but in themselves they are not what make Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy complex, multifaceted characters.

You could assign a character dozens of attributes and personality traits, and spends months writing countless pages of the character’s backstory and history, and yet still not create a character that feels alive.

Then how do you create a multifaceted character?

In the craft book Story: Style, Structure, Substance, and the Principles of Screenwriting, screenwriter Robert McKee makes the argument that the core component in a round or three-dimensional character is “inner contradiction.”

As McKee writes, “Dimension means contradiction.” And dimensions are what fascinate an audience, riveting us to characters as we attempt to understand their complexities.

Real people are filled with contradictions, and at its heart, a powerful story is about a character wrestling with their inner contradictions and the world.

Here are five of the main types of contradictions that can create a multifaceted character:

Contradictions between a character’s wants and needs

Contradictions between the character’s inner self and the world in which they live

Contradictions between how the character interacts with some characters versus with other characters

Contradictions between the simultaneously-held ideals of a character

Contradictions between a character’s ideals and how they live

I’ve written a number of flash fiction stories—all less than 1000 words—where the main characters feel multi-dimensional. In one of these stories, you really only learn two things about the character: 1. She absolutely loves music and listening to vocal performances; 2. She applied multiple times to vocal performance degrees in college and was rejected each time, and has since given up on singing. Her love of music but her rejection of her own musical self as inadequate creates a contradiction within herself, which sets the stage for the story.

What contradictions has Jane Austen created in Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy?

A Few of Elizabeth Bennet’s Contradictions:

- Critical of Mr. Darcy’s pride but holds fast to her own.

- Wants to avoid Mr. Darcy, yet finds herself drawn to him.

- Only wants to marry if it is for love, yet she is pressured by her society and mother to accept any eligible match.

- Instantly trusts Mr. Wickham and accepts his story, yet distrusts and judges whatever Mr. Darcy says.

- Wittily expresses views that are not always her own.

A Few of Mr. Darcy’s Contradictions:

- Prideful yet kindhearted and generous.

- Despises spending time with people he does not know, yet willingly goes to events with Mr. Bingley because he values their friendship.

- Feels the need to save Mr. Bingley from a connection to the Bennet family, but unwilling to do the same for himself.

- Expects Elizabeth to see and accept his virtues, yet says hurtful things to her.

Sometimes I consciously plan a character’s contradictions, yet often, these contradictions develop as I write. Either way, as I enter the revision process, I refine these facets and how they fit together: this is the cutting and polishing of a gemstone.

A few additional notes on characters:

- The core characters should be the most multifaceted characters in a story. Any and all characters can have contradictions, yet if those of a minor character more compelling than those of the main characters, readers can lose interest in the main characters.

- Supporting characters can help reveal the different facets of a main character. Robert McKee writes, “In essence, the protagonist creates the rest of the cast. All other characters are in a story first and foremost because of the relationship they strike to the protagonist and the way each helps to delineate the dimensions of the protagonist’s complex nature.”

Multifaceted characters are complex and three-dimensional. After all, it is our complexities that make us human, and it is unravelling and dealing with these complexities that makes a story.

Exercise 1: Choose one of the following characteristics, attributes, or skills that could belong to a character:

- Charitable

- Athletic

- Loves to read

- Hates traveling

- Good at cooking

- Prone to procrastination

Create a contradiction that could relate to this characteristic or attribute. It could be aspects of this characteristic, how a character applies it in some situations but not other, how it combines or conflicts with another characteristic, or a contradiction between this characteristic and society.

Exercise 2: Choose one of your favorite characters from literature. What are some of their contradictions? If you’d like, share in the comments below.

Exercise 3:

Option 1: Brainstorm a new character that you might use in a story. First, write a brief physical description, assign them several personality traits, give them interests, decide where they live/their occupation, etc., and choose a few key moments from their history/past. Now decide on one or two key contradictions that can make them come alive.

Option 2: For a story that you’ve already written, figure out what the key contradictions are for each of your main characters.