Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#23: Reveal Characters Through Other People’s Perceptions of Them

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

In the past two lessons, I talked about how Jane Austen reveals characters through moments of tension and through character dialogue. Yet there is another method which she frequently uses to introduce and reveal characters to the reader: through the perceptions of others.

One of the ways she does this is by having her characters both think and reference other characters before they physically appear in scene in the story—sometimes long before they physically appear.

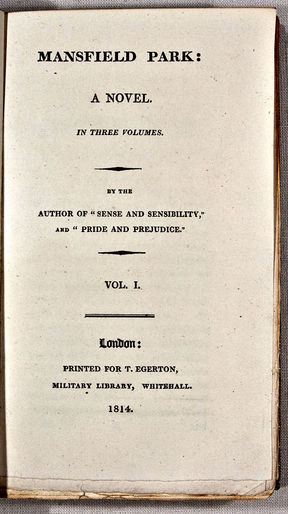

Title page for the first edition of Mansfield Park–from 1814! (Image in the public domain)

One example of this is in Austen’s novel Mansfield Park. At the age of ten years old, Fanny Price goes to stay with her aunt and uncle at Mansfield Park. She’s ripped from her home, her town, and her family. Only her cousin Edmund shows her true kindness, and he gets her to talk about her home. As she does so, we are introduced to the character of William:

On pursuing the subject, [Edmund] found that, dear as all these brothers and sisters generally were, there was one among them who ran more in her thoughts than the rest. It was William whom she talked of most, and wanted most to see. William, the eldest, a year older than herself, her constant companion and friend; her advocate with her mother (of whom he was the darling) in every distress. “William did not like she should come away; he had told her he should miss her very much indeed.” “But William will write to you, I dare say.” “Yes, he had promised he would, but he had told her to write first.” “And when shall you do it?” She hung her head and answered hesitatingly, “she did not know; she had not any paper.”

“If that be all your difficulty, I will furnish you with paper and every other material, and you may write your letter whenever you choose. Would it make you happy to write to William?”

“Yes, very.”

“Then let it be done now. Come with me into the breakfast-room, we shall find everything there, and be sure of having the room to ourselves.”

William continues to be a character that Fanny talks and thinks about throughout the story. He doesn’t actually appear in person until Chapter 24, about halfway through the novel. Yet he plays an essential role in the story:

- He is the only character who never hurts Fanny.

- Fanny loves him with all her heart, and his letters and presence bring her joy, as do mere thoughts of him.

- Because of William’s visit, their uncle throws a ball, which creates a pivotal scene in the story, as Henry Crawford gives his attentions to Fanny and she attempts to reject him.

- Henry Crawford uses his connections to obtain a huge promotion for William, basically making his future career, in an attempt to put Fanny in his debt and make her fall in love with him.

William is introduced to us entirely through Fanny’s perceptions of him. This not only flavors our perceptions of him, but it sets up his role in the story and makes us truly experience Fanny’s agony when she must decide what to do: should she marry Henry Crawford when he proposes to her, especially given what he did for her brother?

Mansfield Park is not the only Austen novel to introduce and reveal characters to us before we see them interacting on the page.

Image by Eymery, Creative Commons license

Further examples of Austen introducing characters before we meet them physically:

Persuasion

-The cousin and heir, Mr. Elliot, is talked about in the very first chapter, focusing on the poor way he has treated the Elliot family. He doesn’t appear in person in the book until about halfway through, but then plays a pivotal role in the second half of the book as he courts Anne. When she is skeptical of his intentions, we sympathize with her, in part because of the way he was introduced at the start of the book.

Pride and Prejudice

–Mr. Bingley is discussed in the first chapter as a prospective suitor for one of the Bennet daughters. This builds anticipation for him as a character, so we, like the daughters, are longing to meet him when he arrives at the Meryton ball.

–Lady Catherine de Bourgh is referenced constantly by Mr. Collins, who reveres her (she is his patroness!). Her influence and power is set up before we meet her, which provides a foreshadowing for the end of the novel, when she attempts to convince Elizabeth not to marry Mr. Darcy.

–Georgiana, Mr. Darcy’s sister, is also frequently referenced by Mr. Darcy himself and the Bingleys throughout the story, as well as by Mr. Wickham. Her story plays a pivotal role on multiple story levels, even though she doesn’t get much time in person on the page.

Emma

–Jane Fairfax is someone long spoken of before she appears on the page. In this case, the main character, Emma, has known her for basically their whole lives. But we as readers only get to hear Jane spoken of through Emma’s negative viewpoint until Jane actually comes to visit. This awareness of Jane as a potential rival for Emma infuses the text. This negative perception of Jane is counterbalanced by Mr. Knightley’s perception of her, who sees her virtues and criticizes Emma’s treatment of her.

–Frank Churchill is loved and anticipated by (almost) everyone, even though he has never visited. We do know that Mrs. Weston is frustrated by the fact that she has never met her stepson, for he has never managed to visit, but in general, people look upon Frank Churchill as a darling. Emma in particular is fascinated by the idea of him:

Now, it so happened that in spite of Emma’s resolution of never marrying, there was something in the name, in the idea of Mr. Frank Churchill, which always interested her. She had frequently thought—especially since his father’s marriage with Miss Taylor—that if she were to marry, he was the very person to suit her in age, character and condition.

While Emma is predisposed to like Mr. Churchill before meeting him, Mr. Knightley already dislikes and distrusts him. Emma’s and Mr. Knightley’s divergent perspectives of two other important characters sets up much of the major conflict and raises some of the novel’s important themes. Who is correct, and what will be the results of everyone’s judgments and behaviors?

As you can see from these examples, there are a lot of potential uses for introducing a character through the perceptions of others. Here’s my attempt to categorize these reasons.

6 Reasons to Introduce Characters Through the Perceptions of Other Characters:

- It predisposes us to feel a certain way about unmet characters (this can be positive or negative).

- It focuses our attention on the character and the role that they will play.

- It allows a character to influence the plot before they appear physically on the page.

- It sets up a sense of relationships and can add a community focus to the story—it is not just individual relationships at stake, but an integrated network of people.

- It draws attention to the lens through which we see characters. The narrator is already providing a lens through with which to see the characters and the story, but this adds lenses. As the story progresses, sometimes we find that we agree with the lenses we’ve been given, while other times we disagree.

- It reveals character for all the characters: both the character we have not yet met, and the characters who are thinking or speaking of that character.

Even once a character has appeared in scene, the evolving perceptions of various people in the story continue to reveal things about character to the reader. For example, in Emma, the way that each of the characters interpret Frank Churchill’s behavior informs us both about them and about Frank. Differing perceptions of character can also be revelatory: in Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy’s negative perceptions of Mr. Wickham warn us of Wickham’s true character, even though many of the characters, such as Elizabeth, do not yet trust Mr. Darcy’s perceptions because of his pride.

Character perceptions are a powerful narrative tool, and using these perceptions to reveal character can be a powerful way to both introduce characters and show their relationships with others throughout the story.

Exercise 1: Spend about five minutes brainstorming a character. Then play Enemy, Friend, Lover to introduce the character to the reader.

Enemy, Friend, Lover: The character you have brainstormed is not present. How would they be talked about by an enemy, by a friend, and by a lover?

You can interpret enemy, friend, lover in any way you choose. For example, an enemy could be a coworker the character doesn’t get along with or a member of a multi-family feud. A friend could be a BFF or a new acquaintance with a shared interest. A lover could be a boyfriend, a spouse, someone involved in an illicit liaison, etc.

Consider also that an enemy, friend, or lover may at times attempt to hide, disguise, or downplay their relationship with the character. If they do that, that reveals things about both the character and themselves.

Write three brief introductions, one each by the enemy, friend, and lover. These descriptions could range from a brief sentence to several paragraphs long.

Exercise 2: Read the first thirty pages of a book or watch the first 30 minutes of a film. Write down every time a character is introduced, and how they are introduced (moment of tension, in dialogue with another character, being talked about while they are not physically present, or through a different method—if a different method, please categorize). Does the story use multiple types of character introductions, or mostly one type? How does the manner in which they are introduced impact the audience?

Exercise 3: Take a story that you have written and choose one of your characters that you have introduced by showing them physically present in a scene. Write a new scene which would introduce them through another character’s perceptions of them.

#22: Reveal Characters Through Dialogue

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

The opening scene of dialogue in Sense and Sensibility belongs not to the main characters, but rather, to their relations. At the beginning of the novel, Mr. Henry Dashwood is dead, and his son, Mr. John Dashwood, has inherited everything; despite Henry’s desires, his second wife and their daughters get nothing from the property. Yet before his death, Henry made his son John promise to take care of his step-mother and three half-sisters.

After this exposition, which is provided by the narrator, the first dialogue of the novel is between John Dashwood and his wife, Fanny Dashwood:

“It was my father’s last request to me,” replied her husband, “that I should assist his widow and daughters.”

“He did not know what he was talking of, I dare say; ten to one but he was light-headed at the time. Had he been in his right senses, he could not have thought of such a thing as begging you to give away half your fortune from your own child.”

“He did not stipulate for any particular sum, my dear Fanny; he only requested me, in general terms, to assist them, and make their situation more comfortable than it was in his power to do. Perhaps it would have been as well if he had left it wholly to myself. He could hardly suppose I should neglect them. But as he required the promise, I could not do less than give it: at least I thought so at the time. The promise, therefore, was given, and must be performed. Something must be done for them whenever they leave Norland and settle in a new home.”

“Well, then, let something be done for them; but that something need not be three thousand pounds.”

From this dialogue, we can already paint a picture of who John and Fanny are, in much more vivid terms than pages of description would provide. John feels familial obligation, and Fanny does not want him to fulfill this obligation to the extent he has planned, which we assume is for selfish reasons.

Good dialogue brings characters to life: it is as if they have stepped from the page and we are watching them, animated before us.

Last week, I talked about using moments of tension to reveal characters to the reader. Effective dialogue is another powerful way to quickly reveal characters to the reader.

While John had planned to give 3000 pounds to his sisters—1000 apiece—he proposes that he cut it in half, giving each of them 500 pounds. And the conversation continues:

“Oh! beyond anything great! What brother on earth would do half so much for his sisters, even if really his sisters! And as it is—only half blood!—But you have such a generous spirit!”

“I would not wish to do any thing mean,” he replied. “One had rather, on such occasions, do too much than too little. No one, at least, can think I have not done enough for them: even themselves, they can hardly expect more.”

“There is no knowing what they may expect,” said the lady, “but we are not to think of their expectations: the question is, what you can afford to do.”

Fanny is skilled at knowing how to maneuver her husband: she praises him for his generosity, and then claims that this is way beyond what anyone would do. She then shifts the conversation to their needs, and ultimately, she will appeal again to the future, hypothetical needs of their young son.

Jane Austen truly has some of the best dialogue of any writer. I could probably write an entire book about how Jane Austen employs dialogue throughout her novels. (Please don’t challenge me to do so—I may not be able to resist the temptation!) In a previous post, I addressed some initial ways that Jane Austen creates dynamic character interactions through dialogue. This post takes it one step further, looking at how dialogue reveals character.

From analyzing Austen’s use of dialogue, I’ve distilled 4 questions that I like to ask myself as I write dialogue for my characters.

4 Key Questions to Ask When Writing Dialogue

1. What is the conversational goal of each of the characters in this conversation?

The writer Kurt Vonnegut famously said, “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.”

Every character comes into a conversation with a different perspective, a different history and personality, and a different relationship with the subject matter. In turn, this creates a different goal. Even people who are close to each other and know each other well, like family members or close friends, come into a conversation with a different goal. Often, a conversational want will be related, in some way, to a character’s larger, overreaching wants and needs in the story.

In this scene in Sense and Sensibility, John wants to do his duty to his father, and he also wants to feel good about himself—he wants to feel morally justified. Fanny, on the other hand, desperately wants to keep all of the money they have just inherited. However, she also wants her husband to feel good about his decisions and comfortable with moral positioning, and she does not want to damage their relationship or come off as cruel and unfeeling.

2. What is the relationship between the characters?

Readers can judge characters’ relationships with each other through a passage of dialogue. This is because relationships always influence the tone of the dialogue, the flow, the approach, and the outcome.

Relationships will determine how open or closed a character is with their intentions. It will impact what they are comfortable saying. It will demonstrate what is at stake for a character.

Some characters, like Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, have no compunction with asserting themselves and speaking their mind in front of a stranger in a position of power and authority, as Elizabeth does to Lady Catherine de Bourgh, and this fact does much to reveal Elizabeth’s character.

When characters shift their behavior because of their relationships, or behave with deference or authority, respect or disdain, it once again is revelatory.

From just a few lines of dialogue, readers can typically determine much about character relationships and their history with each other.

In this opening passage in Sense and Sensibility, the dynamics of John and Fanny’s marriage are made clear, as are other relationships: the relationship between John and his father; the relationships between John, his stepmother, and his half-sisters; and the relationship (or lack of substantial relationship) Fanny has with any of these other characters.

The dynamics become more complication when it shifts from a dialogue between two characters and a dialogue between a larger number of characters. For instance, in a dialogue between four, five, or six characters, there is a web of relationships: individual relationships between each set of characters, and relationships between each individual character and the group as a whole, particularly is someone is an outsider or less established in the group.

3. How is what each character says interpreted by the other characters?

Listening is a constant act of interpreting: interpreting someone’s words and gestures and expressions for meaning and purpose. This interpretation is influenced by a character’s relationships, current emotional state, background on the subject matter, and personality.

When a character interprets another character’s speech, they react both internally—they could impact their mood, their perspective, etc.—and externally, by what they say and do, both immediately and over time.

Throughout this passage, John listens to his wife intently, and he accepts her praise and flattery and justifications. He interprets anything she says favorably, as if she has said it with the best intent.

Before this scene, in the exposition, the narrator tells us of Mr. John Dashwood:

He was not an ill-disposed young man, unless to be rather cold-hearted, and rather selfish, is to be ill-disposed: but he was, in general, well respected; for he conducted himself with propriety in the discharge of his ordinary duties. Had he married a more amiable woman, he might have been made still more respectable than he was:–he might even have been made amiable himself; for he was very young when he was married, and very fond of his wife. But Mrs. John Dashwood was a strong caricature of himself;–more narrow-minded and selfish.

While the narrator has already explained John’s character, here we see it in action as he interprets Fanny’s words and then acts on them.

In the novel The Jane Austen Project, two time travelers, Rachel and Liam, journey to Jane Austen’s time in an attempt to recover an unpublished novel she has written. In first person, we experience the dialogue and Rachel’s interpretation of it:

I was here. We’d done it.

“Are you all right?” I asked again. Liam groaned but rolled over, sat up, and scanned our surroundings of field, birch, and hedgerow. The portal location had been chosen well; nobody was here.

“It’s dusk,” I explained. “That’s why it all looks like this.” He turned toward me, dark eyebrows arching in a question. “In case you were wondering.”

“I wasn’t.” His words came slowly, voice soft. “But thanks.”

I looked at him sideways, trying to decide if he was being sarcastic, and hoped so. In our time together at the institute preparing for the mission, something about Liam had always eluded me. He was too reserved; you never knew about people like that.

At this point in the novel, she clearly does not know Liam very well, and does not know what to make of his words. And yet she must make an interpretation of them in order to continue acting and speaking.

Conversation is a constant act of not just speaking, but of analyzing and coming to conclusions. The conclusions that characters come to reveal who they are to the reader.

4. How susceptible are the characters to influence?

Words are tools of power: we use them to shift and impact reality. How much a character is willing to be influenced by other characters will depend not just on the relationship between characters, but also on character’s relationship to the subject matter.

John Dashwood already is selfish—he cares about money, which makes him more susceptible to persuasion—and he does not have a strong sense of loyalty to his mother and half-sisters.

Yet even though these things make him more inclined to be influenced, Fanny’s delivery is still an important aspect. If she had started with, “We shouldn’t give them anything,” John would have likely found it much less palatable than her bringing him their by degrees.

Fanny, on the other hand, is much less prone to influence in this situation. Her husband makes concession after concession, but she will not stop until she has reached her full goal.

Near the end of the chapter, Fanny says:

“Indeed, to say the truth, I am convinced within myself that your father had no idea of your giving them any money at all.”

She continues on in this manner, and manages to completely convince her husband:

“Upon my word,” said Mr. Dashwood, “I believe you are perfectly right. My father certainly could mean nothing more by his request to me than what you say. I clearly understand it now, and I will strictly fulfill my engagement by such acts of assistance and kindness to them as you have described.”

And thus, by this single conversation, the lives of Mrs. Dashwood, Elinor, Marianne, and Margaret, are forever, irrevocably changed.

In Conclusion

Dialogue is a powerful tool to reveal characters. At any point in the narrative, dialogue will impact our view of characters. The first conversation in which we see a particular character is particularly powerful in its ability to form our initial snapshot of who the character is and the role she will play in the story.

Exercise 1: Read the following short dialogue passage between two (currently unnamed) characters.

“I think we should go with the chips and salsa. It’s easy, inexpensive, and can take care of a lot of people.”

“I think the fruit platter would be better. It’s a lot healthier, and it doesn’t cost that much more.”

“True, but people want something that’s a treat.”

“Strawberries are a treat.”

“Maybe we should just get both.”

Right now, the dialogue is bland, impersonal, and boring. It has no weight in a (hypothetical) story. But you can change that!

Rewrite the dialogue two times, each time taking a different approach in your decision-making:

- Choose who the characters are, and what their relationship is to each other (i.e. strangers thrust together, someone and their ex-, coworkers, estranged family members)

- What is at stake for the characters? Why does this matter to them? What are their goals, and do they differ?

- How do they interpret what the other character says? How susceptible are each of these characters to influence?

Depending on how much time you have, you could set a timer and rewrite the dialogue in 5 to 10 minutes, or you could spend longer if you’d like. You can change anything about the dialogue, and if it’s useful, add description and action. Use this as a launching point and see what happens.

Exercise 2: Track your personal conversations for a day. Who do you speak to? How do your relationships impact your conversations? How do your conversational goals differ from one conversation to the next? How much are you influenced by your conversations, and how much do you influence others?

Exercise 3: What is one of your favorite lines of dialogue? This could be from a book, a short story, or a film. Now go to that scene and analyze the entire passage of dialogue. In particular, consider:

- Conversational goals

- Character relationships

- How the characters interpret each other’s words

- How much the characters are susceptible to persuasion