Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#26: Give Antagonists Understandable Motives (Part 1)

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

As I discussed in the previous post, an antagonist is a person who actively opposes the main character and tries to interfere with them achieving their wants and needs, typically over multiple scenes or a large portion of the story.

One of the things that makes Jane Austen’s protagonists so effective is that they always have understandable motives. As readers, we don’t always know these motives immediately, but ultimately these motives are explainable and understandable.

We’re going to consider four different categories of antagonist’s motives, with examples from Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility. In today’s post, Part 1, we’ll look at more negative types of antagonism, and in the next blog post, Part 2, we’ll consider more positive or neutral types of antagonism.

Self-Interested Motives

The first major category of motives held by antagonists is self-interest.

All characters, antagonists and protagonists, act with a certain amount of self-interest. It’s the only way, as people, we can survive—it’s the only way we get our wants and desires. And we often support characters striving for their wants and needs, and we become frustrated with characters like Fanny Price in Mansfield Park when they don’t actively strive for their wants and needs.

Self-interest becomes antagonism when:

- A character’s self-interest interrupts the protagonist’s journey.

- A character’s self-interest harms other characters, or is done with a regard only for oneself.

In the second category of self-interest as antagonism, we often see:

Selfishness

Emphasis on bodily passions

A focus on gaining power

A focus on gaining wealth or material objects

Disregard for social or societal norms

Ultimately, self-interest is a prioritization of ones own needs and wants over the needs and wants of others.

An example of an antagonistic character acting with self-interest from is found in Fanny Dashwood (of Sense and Sensibility). Fanny does not want to see any of her husband’s inheritance go to his half-sisters or stepmother.

“It was my father’s last request to me,” replied her husband, “that I should assist his widow and daughters.”

“He did not know what he was talking of, I dare say; ten to one but he was light-headed at the time. Had he been in his right senses, he could not have thought of such a thing as begging you to give away half your fortune from your own child.”

Slowly Fanny works her husband down, appealing to their sons supposed needs and other self-focused arguments, until ultimately her husband decides not to give them any money, and only occasionally assist them with minor things:

“Your father thought only of them. And I must say this: that you owe no particular gratitude to him, nor attention to his wishes; for we very well know that if he could, he would have left almost everything in the world to them.”

This argument was irresistible. It gave to his intentions whatever of decision was wanting before; and he finally resolved, that it would be absolutely unnecessary, if not highly indecorous, to do more for the widow and children of his father, than such kind of neighbourly acts as his own wife pointed out.

Another character who acts with self-interest is Lucy Steele. She has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for four years, and now he is in love with Elinor Dashwood. It’s quite understandable that she would act in her own self-interest and attempt to maintain her engagement. She obviously has (or at least, had) feelings for Edward, and this is her chance for a better life. She is a dislikeable character because of the things she does in the name of self-interest, but we’ll talk about that more in the next section.

Outward-Focused Negative Motives

The second major category of antagonist motives are those which are outwardly-negative.

There are a number of these outward-focused negative motives, including:

Spite

Bitterness

Jealousy

Anger

Revenge

Cruelty

A desire to control others

Intentional breaking of social rules, laws, and expectations

All of these motives are manifestations of natural human emotions and inclinations. All people feel them, and most of us have acted with them to some degree or another.

Some characters are fixed in these sorts of motives, embracing them; other resist these motives, or turn to them in moments of extreme pressure, struggle, or pain.

In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Ferrars is generally cruel, controlling, and unpleasant to those around her. When Edward and Lucy’s secret engagement is revealed, she lashes out. In an act of anger and revenge, she disinherits Edward.

(As an interesting note, some scholars and other readers have noted that Mrs. Ferrars and Fanny Dashwood are both characters of power who are using and maintaining power in a society where traditionally women don’t hold any power. Even though I still find them to be unlikeable characters, this perspective helps me understand, and in some ways sympathize, with their motives.)

Sometimes acting on negative motives happens in the moment. At other times, as in the case of Lucy Steele, it’s planned and premeditated.

Lucy realizes that Edward has fallen in love with Elinor, so she is intentionally manipulative. She “confides” her troubles about her secret engagement to Elinor, after extracting a promise that she will not tell a soul. And then she continues to be intentionally cruel and manipulative, manifesting a fair amount of spite towards Elinor.

In Conclusion

These negative motives for antagonism are very common in literature: even in Sense and Sensibility, there are numerous examples. In a sense, they are an answer to the question—what happens if we stop following societal rules and expectations for “good behavior”? This makes for good storytelling, because it creates the opportunity for conflict.

In the next lesson, we’ll focus on positive (as well as neutral and mixed) motives for antagonism.

Exercise 1: Negative Perspectives

Some stories explore the perspective of a character fueled by negative motives. For example, in The Count of Monte Cristo, we see someone driven by revenge. And in the story of Robin Hood, a transgression of societal rules and laws (continuous theft of money and property) is shown to be justified as we see his reasons and what he does with this wealth (gives it to the poor).

Other stories, like The Wizard of Oz, give understandable motives to the villains, but still do not allow us to sympathize with them (the wicked witch is understandably angry at Dorothy for killing her sister, yet we are ). Some stories, like Wicked, explore more fully the seemingly negative motives of antagonists—here, the “wicked” witch is not truly wicked, despite some of her negative motives and choices.

Choose a story that does not explain or develop the antagonist’s motives, and write a paragraph or two exploring what their motives might be.

Exercise 2: Good Actions, Negative Motives

Many times, we assume that good actions must have positive motives behind them. Yet good actions can just as well be driven by negative motives. Good actions can be driven by self-interest, or by outward-facing negative emotions, like jealousy, revenge, or a desire to control others.

Set a timer for 3 to 5 minutes. During the time, come up with a negative motive that could drive each of the following actions. If you have time, write extra details about how this motive would play out during the scene.

- Donating to a charity/volunteering at a food bank

- Throwing a large party and inviting the whole neighborhood

- Revitalizing a city’s downtown

- Running for the school board

- Creating a new work of art

Exercise 3: Protagonists with Negative Motives

Antagonists with negative motives are interesting, but sometimes, protagonists with negative motives can be even more interesting.

Option 1: Brainstorm a protagonist that is sometimes driven by negative motives. In what sorts of circumstances do they act on these negative motives? When do they resist these negative motives? What are positive and negative effects of theme acting on these negative motives?

Option 2: Analyze a draft that you have written. At what points is your character driven by negative motives? Is there a point where it would be useful to give the character a negative motive?

2020 In Review, and Writing like Alexander Hamilton

/3 Comments/in Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, Updates, Year in Review/by Katherine CowleyThe time has come—the long-awaited time of year in which I interrupt your life with charts, beautiful charts!

It’s year in review time. And despite the trash fire that 2020 has been overall, it’s been a really good writing year for me.

(Now I do feel a little self-conscious about it having been a good writing year. So many people have struggled with so much this year—loss of loved ones, personal health, jobs, etc. And as a result of those things or just general 2020ness, many people who have wanted to write have found themselves unable to write. I have a friend who has dozens of published books, and she has not been able to write much this year at all. If this is what your year was like, don’t need to beat yourself up for it. There are times and seasons for everything, and if you weren’t able to write or progress towards your personal goals this year, there will be years where you can.)

And now, on to my charts.

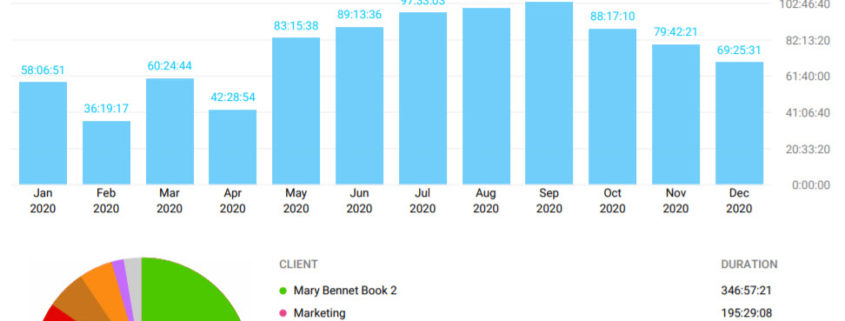

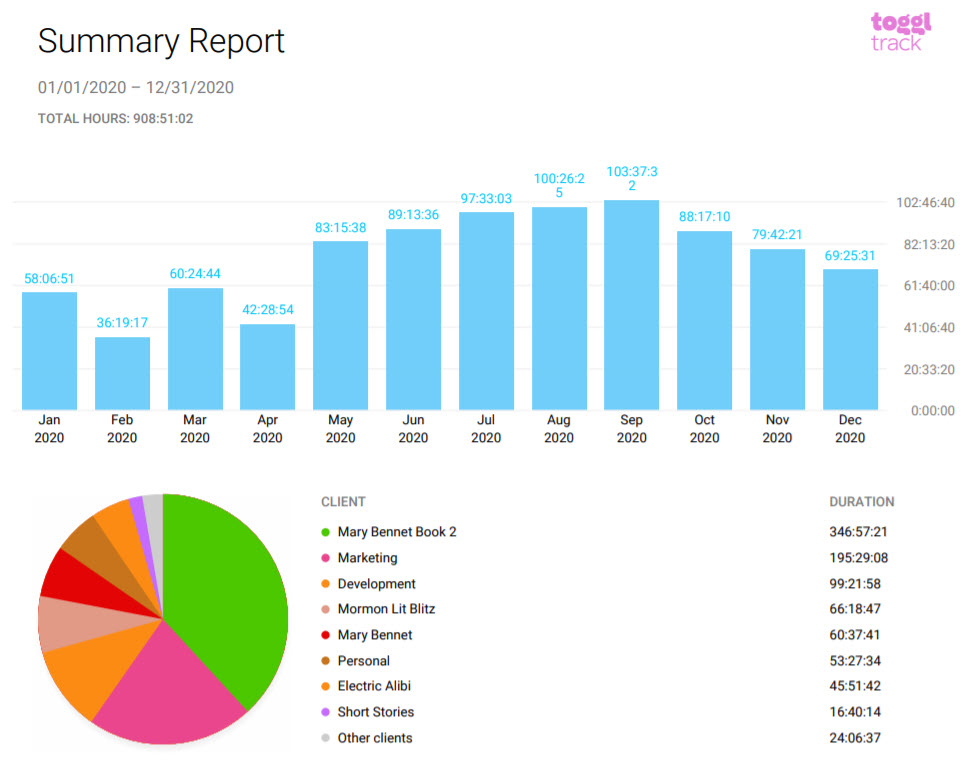

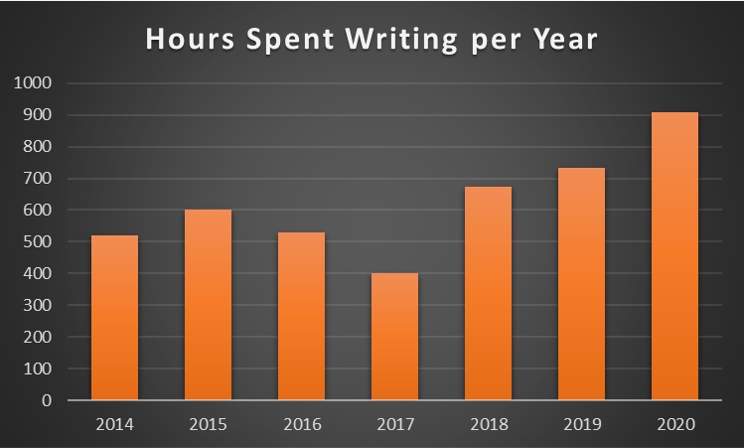

This Year I Wrote for 909 Hours

Note: by “writing” I include research, outlining, revision, planning, writing group, critiquing, listening to writing podcasts, writing accounting, etc…. For example, the “marketing” category includes a multitude of things, including my website (which I revamped this year), blog posts, writing-related social media posts, and conferences and library presentations (I gave two presentations this year). Development includes critiquing, writing group, networking, listening to writing podcasts, and reading books about writing craft.

909 hours works out to an average of 2.5 hours every single day including weekends (if you only include weekdays, it would be an average of 3.5 hours per day). So basically, it was my part-time job.

This is by far the most I have ever written in a year. As evidence, I present another chart:

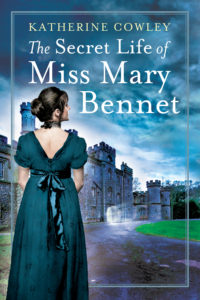

The bulk of my time this year was spent working on my Mary Bennet series. (Which relates to my biggest writing news of the year—I got a three-book-deal with Tule!)

This year I spent 60 hours on the first Mary Bennet book (revisions and copy edits for Tule), 347 hours on the second Mary Bennet book (starting with the second draft, and revising it until it was ready to submit to Tule), and 9 hours on the third Mary Bennet book (this is the one I wish I had spent more on, because I really need to make progress on book 3).

Here’s the cover of the first book, which will be out on April 22nd, 2021:

(If you use Goodreads and haven’t yet added the book to your shelves, here’s the link!)

Another task that I put a lot of hours into was my Jane Austen Writing Lessons. I spent 125 hours on them, and I feel like the posts are really useful in terms of writing craft (and writing them has been a great diversion for me—it’s refreshing to write something that’s more essay-ish rather than fiction). Interesting note—of the 94,500 new words I wrote this year, 36,500 words were on Jane Austen Writing Lessons. So I’ve basically blogged half of a nonfiction book, which is pretty cool, to be honest.

How in the World Did I Write 909 hours during a Global Pandemic?

In part, this was due to the fact that I sort of lost my job this year.

I wasn’t fired. But due to university budget constraints, I wasn’t assigned a section to teach this fall, so I’m not working, and I’m not getting paid. Because I wasn’t actually fired, I can still access the university library (including the Oxford English Dictionary online) and keep my subscription to the New York Times.

Not working has had the side effect of giving me extra hours to write.

Also, the lack of going places and doing things this year has given me extra hours. For instance, I typically write a lot less in the summer, due to driving my kids to lessons and activities, as well doing a bit of travel. Suddenly, this summer, I had a lot more time, and my kids have now hit an age where they were better at entertaining themselves and each other.

Yet the biggest reason I’ve managed to write so much is that I’ve been channeling Alexander Hamilton (or at least the Lin-Manuel Miranda version of him)

Two of my favorite lines from Hamilton are in the song “Non-Stop”:

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

How do you write like you need it to survive?

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

This year, I’ve felt like I’m running out of time. And I accept full responsibility for this. When my agent started pitching The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet to publishers at the beginning of the year, I already had written a first draft of the second book in the series. So I was confident that if the series was picked up by a publisher, I could revise book 2 this year.

Lo and behold, Tule acquired the entire trilogy, and in my contract listed the date by which I would submit book 2 to them. November 1st, 2020. This was the date I provided, but it ended up being a challenging date to reach.

The book needed a lot more work than I realized—it was a hard book to write, a hard year for me to resolve story problems and actually get words onto the page, and so I spent the entire year writing and revising like I was running out of time. But I made the deadline, and I’m really happy with the results!

(The thing is, I would probably set a similar deadline for myself if I was writing a new trilogy. I would just keep my fingers crossed that there wouldn’t be a global pandemic during the process of writing.)

Why do you write like you need it to survive?

Writing has been one of the things that give me joy, that makes me feel steady and centered, and that gives me purpose and direction. And it truly helped me get through this year. So yes, I need writing to survive.

That and chocolate. Does anyone have chocolate? (I’ve somehow ran out of chocolate…)

Goals for 2021

- Successful launch of my debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet

- Write and revise Mary Bennet book 3

- Finish up a quick revision of an old steampunk mystery novel that I shelved for a few years

If I do these three things, I will be happy. (Also, I have to do the first two, because I’ve signed a contract, so…so I better go listen to some more Hamilton.)

Thanks for joining me on my writing journey!

(Also–side note. If you’re not subscribed to my newsletter, I sent out a newsletter today about how I recently deleted 100 pages from the aforementioned steampunk mystery novel. You can read about it by clicking on that link. And if you don’t want to miss future newsletters, subscribe below.)