Full Sized Blog Element (Big Preview Pic)

#48: Techniques for Writing About Holidays in Fiction

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

Jane Austen has a thing for Christmas.

In some of her novels, Christmas is mentioned only in brief, while in others it is a focal component, but each of her six published novels incorporates Christmas in some way. In this post, we’re going to look at how Jane Austen uses Christmas as a storyteller, and what writing techniques we can learn from her. Whether your characters celebrate Christmas or Eid or Rosh Hashanah, you can apply these techniques for writing about holidays in fiction to your own stories.

Technique 1: Use Holidays as Time Markers

Major holidays act as time markers in the year—they are days that are out of the ordinary, and we associate them with certain months and seasons. Austen often references Christmas a time marker, to show either a sense of when something occurred or will occur, or to show the passage of time.

She does this a number of times in her novels, but here’s a few brief examples.

Mansfield Park

In Mansfield Park, there is a conversation between Miss Crawford and Edmund Bertram. They share a romantic interest in each other, but Miss Crawford looks down on the clergy as a profession, while Edmund looks forward to becoming a clergyman:

“Ordained!” said Miss Crawford; “what, are you to be a clergyman?”

“Yes; I shall take orders soon after my father’s return—probably at Christmas.”

Pride and Prejudice

After the regiment leaves Meryton, initially a number of members of the Bennet family are devastated. Eventually, their intense feelings on the matter begin to subside:

Mrs. Bennet was restored to her usual querulous serenity; and, by the middle of June, Kitty was so much recovered as to be able to enter Meryton without tears; an event of such happy promise as to make Elizabeth hope that by the following Christmas she might be so tolerably reasonable as not to mention an officer above once a day…

Technique 2: Use Holidays to Convey Emotions

Holidays are not joyful for everyone: there is not a unified experience or emotional reaction for any holiday. Jane Austen uses holidays to demonstrate a range of emotional states. Sometimes, the emotions shown will be about the holiday itself, or people’s expectations and experience of the holiday. At other times, she will use a holiday to reflect a character’s overall emotional state at this point in the story.

This passage in Persuasion does both: we see characters’ emotions about the present holiday (which in part is related to their expectations for it). Lady Russell expects a quieter holiday than Mrs. Musgrove. We also see characters’ emotional states about the present events—Anne is still troubled by Louisa Musgrove’s accident and the resulting health consequences, and so she expects something different from Christmas, while Mrs. Musgrove finds the Christmas chaos to be a balm for her worries about her daughter Louisa.

Immediately surrounding Mrs Musgrove were the little Harvilles, whom she was sedulously guarding from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them. On one side was a table occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others. Charles and Mary also came in, of course, during their visit, and Mr Musgrove made a point of paying his respects to Lady Russell, and sat down close to her for ten minutes, talking with a very raised voice, but from the clamour of the children on his knees, generally in vain. It was a fine family-piece.

Anne, judging from her own temperament, would have deemed such a domestic hurricane a bad restorative of the nerves, which Louisa’s illness must have so greatly shaken. But Mrs Musgrove, who got Anne near her on purpose to thank her most cordially, again and again, for all her attentions to them, concluded a short recapitulation of what she had suffered herself by observing, with a happy glance round the room, that after all she had gone through, nothing was so likely to do her good as a little quiet cheerfulness at home.

Louisa was now recovering apace. Her mother could even think of her being able to join their party at home, before her brothers and sisters went to school again. The Harvilles had promised to come with her and stay at Uppercross, whenever she returned. Captain Wentworth was gone, for the present, to see his brother in Shropshire.

“I hope I shall remember, in future,” said Lady Russell, as soon as they were reseated in the carriage, “not to call at Uppercross in the Christmas holidays.”

Technique 3: Use Distinctive Holiday Details

At times, Austen gives distinctive details surrounding Christmas. This gives flavor to the holiday and paints the setting for the reader. As a modern reader, these details are fascinating, but they would also be interesting for a contemporary reader because they show how a particular character or group interacts with the holiday.

In the above passage from Persuasion, here are some of the distinctive details included about Christmas:

- Girls cutting up silk and gold paper

- A table covered by “tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies”

- A “roaring Christmas fire”—a loud, large fire, louder and larger because it is for Christmas

The novel Sense and Sensibility includes only two brief references to Christmas, and yet the details included do give flavor to both the holiday and the character’s experience.

After Marianne Dashwood falls down a hill and is rescued by John Willoughby, the incident is mentioned by the Dashwoods to their friend Sir John, and Sir John gives several details praising Willoughby’s character, including the following with a reference to Christmas:

“He is as good a sort of fellow, I believe, as ever lived,” repeated Sir John. “I remember last Christmas at a little hop at the park, he danced from eight o’clock till four, without once sitting down.”

Here, we have details about Christmas—an outdoor party at the park, with dancing for eight hours!

Technique 4: Use Holidays for their Associations

Every holiday has a set of associations for both characters and readers. Some of these associations are universal—Christmas, for example, is associated with celebration and community and gathering as family and friends—while some may be more distinct.

In Emma, when the characters are at Box Hill, the characters begin sharing conundrums—a sort of riddle—and other plays on words. When it comes to Mrs. Elton, she says:

“Oh! for myself, I protest I must be excused,” said Mrs. Elton; “I really cannot attempt—I am not at all fond of the sort of thing. I had an acrostic once sent to me upon my own name, which I was not at all pleased with. I knew who it came from. An abominable puppy!—You know who I mean (nodding to her husband). These kind of things are very well at Christmas, when one is sitting round the fire; but quite out of place, in my opinion, when one is exploring about the country in summer.”

Mrs. Elton’s excuse for not participating is that it is not Christmas.

At other times these associations create emotional touchstones for the reader.

One of my favorite podcasts, The Thing About Austen, recently aired an episode about Elizabeth’s invitation for the Gardiners to join her for Christmas at Pemberley—first, Christmas is set up as a family event in the novel, for which the Gardiners always come to visit; then, Elizabeth supposes that it is good that she did not marry Mr. Darcy, for he would not allow the Gardiners to visit; and then, Elizabeth invites the Gardiners for Christmas. It’s an 18-minute episode, and well worth listening to for the way they analyze these passages and the details they include about Christmas in the Regency.

Technique 5: Use Holidays for Key Scenes

In a previous post, I discussed how distinctive settings are often used for key scenes and turning points.

A holiday can provide a perfect opportunity for these key scenes or turning points—there is lots of emotions, and characters are often gathered together.

The most famous holiday scene in Austen’s works is the Christmas Eve dinner at the Westons in Emma. Its untimely end due to the snow leads to Mr. Elton’s unwanted proposal to Emma in a carriage. I discuss this scene in more depth in my post on using distinctive settings for major plot turns.

The other key scene which occurs at Christmas is the ball thrown for Fanny and her brother in Mansfield Park. This is the first time Fanny’s uncle has truly given her any attention—it is, perhaps, the first time she has felt valued by him. It provokes an internal crisis, as Fanny must decide whether to wear the necklace given her by the Crawfords or the one given by her cousin Edmund. And it is also an event where Henry Crawford gives Fanny his attentions as he attempts to make her fall in love with him. It’s an important scene with many key plot and character moments that change the course of the story.

Conclusion

While Austen often references Christmas, these techniques can be used for incorporating other holidays in fiction as well. Holidays are not an essential or required part of storytelling, yet every single culture and people celebrates holidays. Including holidays can give a fullness to the characters’ lives and show how they behave in circumstances which are out of the ordinary.

Exercise 1: Other Holidays

Choose a holiday that is not Christmas that your characters would celebrate. Write either a reference to the holiday or a full scene which uses at least one of the techniques in this lesson. Make sure to consider what associations the characters would have for the holiday and how they would celebrate it.

Exercise 2: A Holiday Story

Some of the most famous works of fiction, like A Christmas Carol, use a holiday as a core focus and setting for the entire story.

Holiday stories are often associated with certain genres, such as romance, however, holiday stories can be used in any genre—horror, science fiction, mystery, etc.

Outline a short story or novel, of any genre, which uses a holiday as a core component and setting.

Exercise 3: Read or Watch

Read or watch a story which incorporates a holiday, either in a small or large way. Does the story use the same techniques as Austen, or different ones?

#47: Have Characters Justify Their Behavior

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

Characters constantly justify their behaviors and their perspectives—especially their negative behaviors and perspectives. It is the only way for people to live with themselves: they must feel like their actions and viewpoints are justifiable. If they can’t justify their behaviors, then they will feel guilt, shame, or sorrow. These negative emotions can either lead them to change and grow and try to do differently (as Emma ultimately does in Austen’s novel), or the character may choose to suppress their guilt and other negative emotions and find new justifications for their behavior.

Lady Susan, from Austen’s novella Lady Susan, is an excellent example of a character who justifies her negative behaviors and perspectives.

Near the start of the story, she writes a letter to her friend Mrs. Johnson:

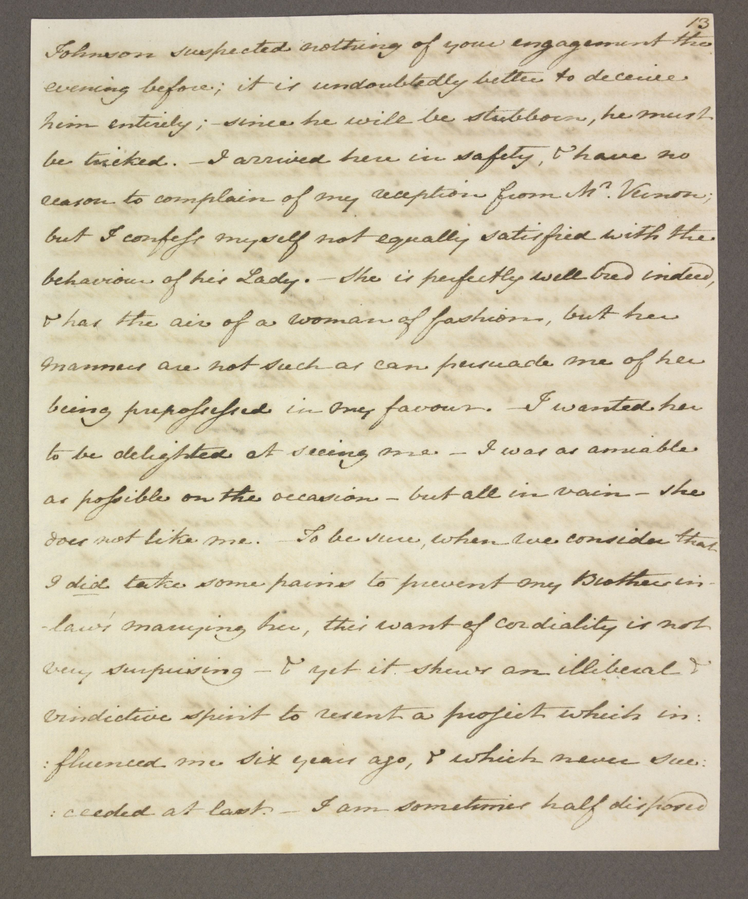

“I received your note my dear Alicia, just before I left Town, and rejoice to be assured that Mr. Johnson suspected nothing of your engagement the evening before; it is undoubtedly better to deceive him entirely;–since he will be stubborn, he must be tricked.”

Here’s part of the passage in Jane Austen’s handwritten manuscript–it appears in the first few lines.

Page 13 of Jane Austen’s original manuscript of Lady Susan. The entire manuscript is in the public domain and can be found on Wikimedia Commons.

Lady Susan uses strong words to describe her own behavior, words that generally have negative connotations: deceive, trick. Yet she feels no guilt.

Characters justify themselves when they feel they have good reasons, and that their behaviors and perspectives are necessary for the situation.

In this case, she feels a need to spend time with her friend Mrs. Johnson, despite Mr. Johnson discouraging their relationship. The only way that she can see Mrs. Johnson is through deceit, which, in her opinion, is necessary because of his stubbornness.

Later in the letter, Lady Susan writes about her experience staying with her deceased husband’s brother, Mr. Vernon, and his wife, Mrs. Vernon:

“I wanted her to be delighted at seeing me—I was as amiable as possible on the occasion—but all in vain—she does not like me.—To be sure, when we consider that I did take some pains to prevent my Brother-in-law’s marrying her, this want of cordiality is not very surprising—and yet it shews an illiberal and vindictive spirit to resent a project which influenced me six years ago, and which never succeeded at last.”

Lady Susan is displeased with Mrs. Vernon’s treatment of her, and she does glimpse the truth, that her own behavior has been at fault.

Even the most despicable characters will generally recognize that they are at least partially at fault in a situation or that they contributed to it in some way.

Yet Lady Susan does not use this recognition in a way that allows for future growth. She does not apologize to Mrs. Vernon, and she does not change her behavior. Instead, she points a finger at Mrs. Vernon.

Characters justify themselves by either placing the blame for their behavior elsewhere, or by pointing to someone else’s behavior as being worse or less justified than their own behavior.

Lady Susan soon sets her eyes on Mrs. Vernon’s unmarried brother, Mr. Reginald De Courcy. Mrs. Vernon writes to her mother, Lady de Courcy:

Lady Susan’s intentions are of course those of absolute coquetry, or a desire of universal admiration.

Coquetry is flirtation, often a sexual flirtation, and was seen very negatively in the time period. In Mrs. Vernon’s letter, she details Lady Susan’s artifice. Yet Lady Susan represents herself in this situation very differently as she writes to Mrs. Johnson:

“I am much obliged to you my dear Friend, for your advice respecting Mr. De Courcy, which I know was given with the fullest conviction of its expediency, tho’ I am not quite determined on following it.—I cannot easily resolve on anything so serious as Marriage, especially as I am not at present in want of money….

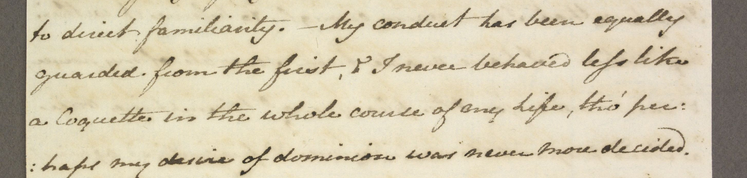

“It has been delightful to me to watch his advances towards intimacy, especially to observe his altered manner…My conduct has been equally guarded from the first, and I never behaved less like a Coquette in the whole course of my Life, tho’ perhaps my desire of dominion was never more decided.”

An excerpt from page 32 of the original manuscript of Lady Susan. Available in the public domain through Wikimedia Commons.

Characters are apt to interpret and represent the same events in a way that paints themselves most favorably. While Mrs. Vernon see coquetry, Lady Susan insists that “I have never behaved less like a Coquette in the whole course of my Life.”

As we look at Austen’s works, we see many other characters justifying themselves—in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth justifies her condemnation of Mr. Darcy and her occasional mistreatment of him. In Emma, Emma justifies her belief of knowing better than anyone else, and she justifies her treatment and judgment of Jane Fairfax and Miss Bates.

In all of these cases, we see that the characters must justify their negative perspectives and outward behavior both to themselves and to select characters around them.

Lady Susan never changes—she digs into her position, and does worse and worse things throughout the novella.

Emma and Elizabeth both are forced to see gaps in their justification; their encounter evidence which challenges their viewpoints; they can see the negative impact of some of their actions. Rather than leaning into their justifications, as Lady Susan does, they both make changes in their lives. Note: Emma at first does resist change, and does resist recognizing her error, even after seeing negative consequences for her behavior; it is only at the end of the book that she makes a change. Elizabeth’s perspective on Mr. Darcy begins to change after the midpoint of the novel, upon reading his letter.

Exercise 1: Make a list of ten negative behaviors or actions (these could be anything—yelling at someone, cutting someone off on the road, not paying a bus fare, etc). Now write down a justification a character could have for each behavior. Make sure to use each type of justification at least once (necessary/have a good reason for it, placing blame elsewhere, someone else’s behavior is worse, interpreting the event more favorably for themselves).

Exercise 2: Choose a book not written my Jane Austen. Find a moment when a character justifies their behavior to themselves, and another moment when they justify their behavior to someone else. Do they use the same justifications or different? How does the other person respond, and how does the character react to that response?

Exercise 3: Option 1: for a story you have planned, find a scene or a moment where your character has an objectionable perspective or behaves in a negative or harmful way. Brainstorm ways they might justify themselves, and, if you’re ready, write the scene.

Option 2: Most characters have an objectionable perspective or perform a harmful action at some point. For a story you have drafted, does your character have any objectionable perspectives or harmful actions? Does the character justify themself? If not, add a justification. If they already have a justification, try to improve their justification.