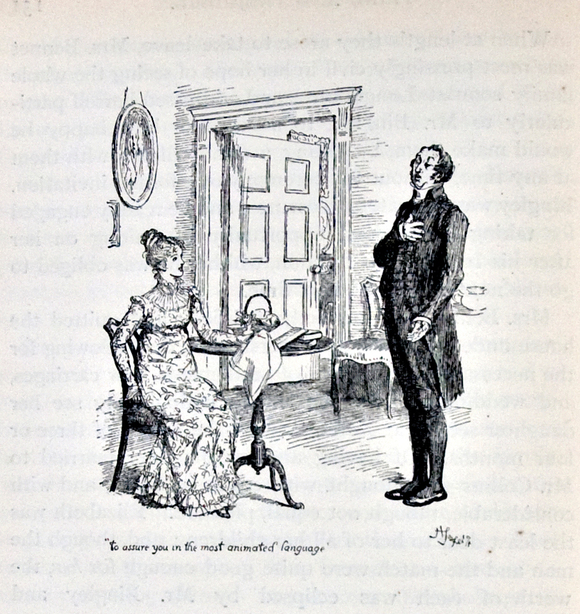

1894 illustration of Mr. Collins’ proposal by Hugh Thompson, public domain

Let’s consider his first paragraph:

“Believe me, my dear Miss Elizabeth, that your modesty, so far from doing you any disservice, rather adds to your other perfections. You would have been less amiable in my eyes had there not been this little unwillingness.”

Pathos #1: Collins attempts to appeal to Elizabeth’s emotions by complimenting and flattering her. He does not recognize that she is not interested in flattery.

but allow me to assure you, that I have your respected mother’s permission for this address.

Ethos #1: he appeals to authority by explaining that he has her mother’s permission to address her. Yet her mother is not a true authority in her life: Elizabeth is much more likely to heed her father, and she also likes to go her own way.

You can hardly doubt the purport of my discourse, however your natural delicacy may lead you to dissemble; my attentions have been too marked to be mistaken. Almost as soon as I entered the house, I singled you out as the companion of my future life. But before I am run away with by my feelings on this subject, perhaps it would be advisable for me to state my reasons for marrying—and, moreover, for coming into Hertfordshire with the design of selecting a wife, as I certainly did.”

Pathos #2: “Run away with by my feelings.” This is an expression that points to emotions without actually conveying any, and further, it doesn’t match his persona. There is a lack of alignment between himself as a speaker and this rhetorical flourish, and in the following line, we learn that Elizabeth finds this lack of alignment amusing.

The idea of Mr. Collins, with all his solemn composure, being run away with by his feelings, made Elizabeth so near laughing, that she could not use the short pause he allowed in any attempt to stop him further, and he continued:

“My reasons for marrying are, first, that I think it a right thing for every clergyman in easy circumstances (like myself) to set the example of matrimony in his parish;

Logos #1: he makes a logical argument, on why, in general, clergymen should marry. Yet this sort of abstract argument presents a sort of fallacy—it does not follow that Elizabeth should marry him.

secondly, that I am convinced that it will add very greatly to my happiness;

Pathos #3: he, personally, wants happiness. Self-centered arguments are often less effective.

and thirdly—which perhaps I ought to have mentioned earlier, that it is the particular advice and recommendation of the very noble lady whom I have the honour of calling patroness. Twice has she condescended to give me her opinion (unasked too!) on this subject; and it was but the very Saturday night before I left Hunsford—between our pools at quadrille, while Mrs. Jenkinson was arranging Miss de Bourgh’s footstool, that she said, ‘Mr. Collins, you must marry. A clergyman like you must marry. Choose properly, choose a gentlewoman for my sake; and for your own, let her be an active, useful sort of person, not brought up high, but able to make a small income go a good way. This is my advice. Find such a woman as soon as you can, bring her to Hunsford, and I will visit her.’ Allow me, by the way, to observe, my fair cousin, that I do not reckon the notice and kindness of Lady Catherine de Bourgh as among the least of the advantages in my power to offer. You will find her manners beyond anything I can describe; and your wit and vivacity, I think, must be acceptable to her, especially when tempered with the silence and respect which her rank will inevitably excite.

Ethos #2: Mr. Collins pulls out what he believes is his strongest argument. To him, the ultimate authority on all matters is Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

In order for this argument to work, Elizabeth would need to share an implicit assumption—that Lady Catherine is an authority figure.

Yet Elizabeth has never even met Lady Catherine…and further, Elizabeth does not believe that those of a superior rank are innately superior to her.

Thus much for my general intention in favour of matrimony; it remains to be told why my views were directed towards Longbourn instead of my own neighbourhood, where I can assure you there are many amiable young women. But the fact is, that being, as I am, to inherit this estate after the death of your honoured father (who, however, may live many years longer), I could not satisfy myself without resolving to choose a wife from among his daughters, that the loss to them might be as little as possible, when the melancholy event takes place—which, however, as I have already said, may not be for several years. This has been my motive, my fair cousin, and I flatter myself it will not sink me in your esteem.

Logos #2 and Pathos #4: From a logical standpoint, wanting to save a family from financial ruin when you have no obligations to them is a charitable and kindly thing to do. “Look at my good motives!” he says.

And now nothing remains for me but to assure you in the most animated language of the violence of my affection.

Pathos #5: Ah, such violent emotions! Which just goes to show that the addition of adjectives doesn’t always help or prove your case.

To fortune I am perfectly indifferent, and shall make no demand of that nature on your father, since I am well aware that it could not be complied with; and that one thousand pounds in the four per cents, which will not be yours till after your mother’s decease, is all that you may ever be entitled to. On that head, therefore, I shall be uniformly silent; and you may assure yourself that no ungenerous reproach shall ever pass my lips when we are married.”

Apophasis: Here Mr. Collins pulls out a really fun rhetorical device, apophasis, which is talking about something by saying you’re not going to talk about it. In other words, he is denying that it matters to him—yet if it truly did not matter at all to him, would he mention it? And he clearly knows exactly how much Elizabeth is worth financially…

As the scene proceeds, Elizabeth turns down Mr. Collins. He attempts to make more arguments, and she becomes more forceful in his rejections.

Ultimately, Mr. Collins’ persuasion fails because he doesn’t understand his audience. It is almost impossible to persuade someone unless you can really understand them, and their perspective. It is almost impossible to persuade someone unless you share implicit assumptions.

It’s easy to assume that people are like us. That the arguments that would work on us would work on them.

It’s also easy to assume that adding more arguments, more proof, will better help us reach our goals. Yet these nine instances of ethos, pathos, and logos were not enough—in fact, some of them directly hurt his cause.

If Mr. Collins wanted Elizabeth to marry him, the heavy work of persuasion would’ve needed to be fulfilled before this. (And often, the most persuasive arguments are made a little at a time.)

Yet ultimately, I don’t think there is a single argument Mr. Collins could have made that would have convinced Elizabeth to marry him. Even the best persuasion won’t persuade someone if they aren’t open to change.

You may write the rare character who is generally persuasive. Yet most of our characters have moments where they fail at their goals—where tension and conflict are created by them trying to persuade others, but not doing so in effective ways.

Certainly our Collins-esque characters should struggle with persuasion, but so should our Elizabeths and Darcys and Wickhams.

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing