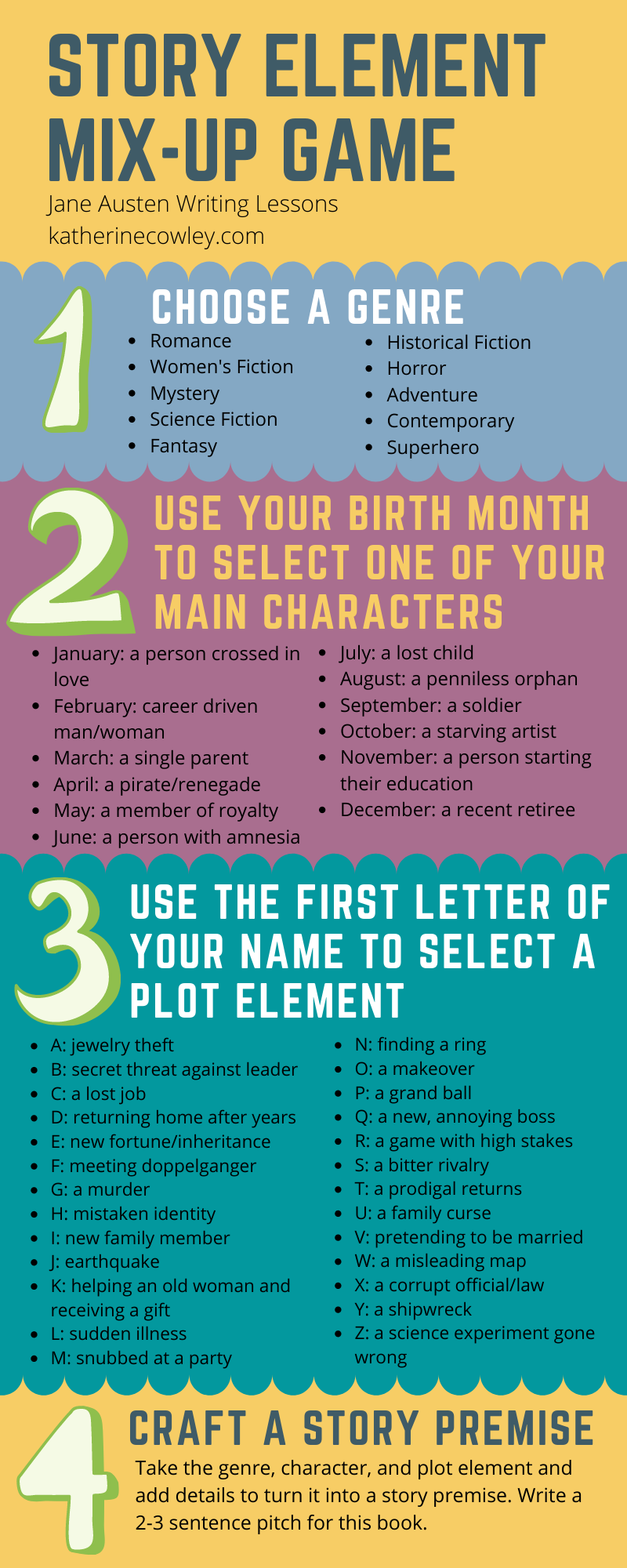

As an example, I have selected the following elements:

- Historical fiction

- Person crossed in love

- Helping an old woman and receiving a gift

Now I will add some additional details in order to craft a story premise:

The widow Lady Gertrude thought she had found love again, but the charming Mr. Wenton was actually a swindler who robbed her of 1000 pounds. Now she is fighting to keep her deceased husband’s estate, while struggling to help the ailing, old housekeeper, Mrs. Winter. Lady Gertrude cares for Mrs. Winter personally, and with her dying breaths Mrs. Winter tells her the location of hidden chest. Inside, Lady Gertrude discovers a family secret: a record of her deceased husband’s disinherited cousin, the scarred and troubled Colonel Anthrop, who may hold the key to saving both the estate and Lady Gertrude’s broken heart.

If you would like to do the exercise more than once, use the birth month and name of a friend, or change the genre. (Or go rogue and choose whichever elements from the chart you would like!)

If I were to create a story premise with the same components but a different genre (superhero), my story premise might look like this:

Angela moves to a small town in the upper peninsula of Michigan to escape her past—and her cheating ex-boyfriend. As she’s moving into an old, one-bedroom apartment, she helps an old woman with her groceries. The brownies the old woman gives her as a thank-you give Angela superpowers, including the ability to sense when a crime is being committed. Soon she discovers a conspiracy involving the famous Tahquamenon Falls, and Angela must use her powers to save her newfound community.

Exercise 2

Brainstorm a list of story ideas. These do not have to be fully developed story ideas—rather, they can be interesting story elements. The film director Michael Rabiger recommends keeping a CLOSAT journal, where you record interesting Characters, Locations, Objects, Situations, Acts, and Themes. These can be from life, from your imagination, from other stories or art, from the news, etc. Once you find a story element you really like, see what you can combine it with to develop a story.

Exercise 3

If you are already working on a short story or a novel, practice writing an elevator pitch: a short, 1-2 sentence pitch about your story that you could give to someone in the length of time you would spend with them in an elevator. Consider which core elements make your premise unique and compelling, and see if you can capture the core conflict of the story in your pitch. As a bonus challenge, pitch your story idea to five different people.

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing