A memorial ring from 1804 or 1805 with locks of hair set between pearls. Mourning rings were given out to family and close friends at funerals, and often included locks of hair. In Sense and Sensibility it is clear that a ring with a lock of hair was not assumed to be a mourning ring, and that it was quite common for the ring to commemorate a living person. This ring is also owned by the Walters Art Museum. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

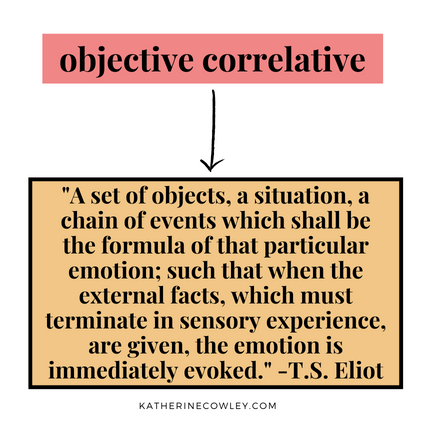

A few chapters later, as the chain of events progresses, Austen once again uses this same lock of hair. This is the prime example of what T.S. Eliot’s emotional formula, for she has set up the object to produce a very specific emotion from the reader.

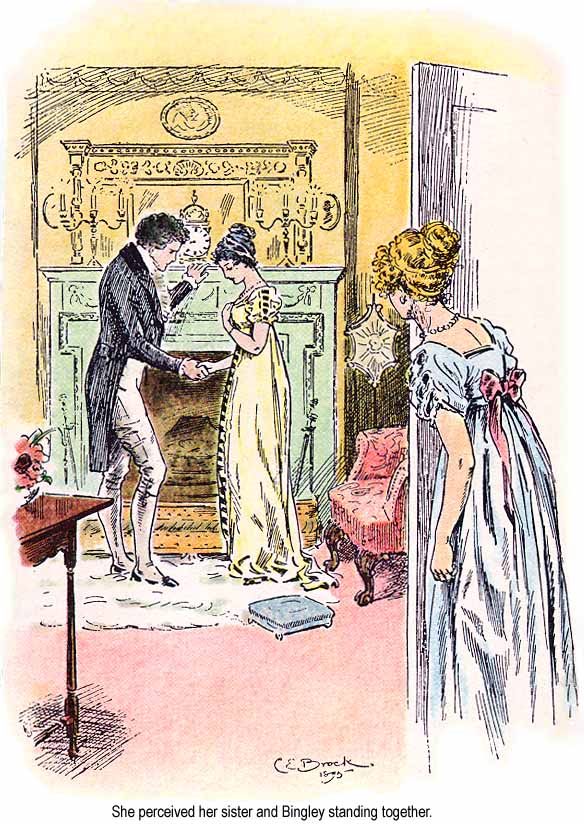

What happens is that Elinor meets Lucy Steele. Lucy deduces that Elinor is in love with Edward, but Lucy is also in love with Edward, and she wants to mark her territory.

Lucy makes Elinor promise not to tell anyone what she is about to share, and then she confides in Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward for four years.

Elinor cannot believe her, but Lucy provides more and more evidence, including dates and places that align with Elinor’s knowledge of Edward’s whereabouts, a miniature painting of Edward, and a letter written in Edward’s hand.

Then Lucy manages to completely decimate both Elinor and the reader’s emotions by bringing back a reference to the key object:

“Writing to each other,” said Lucy, returning the letter into her pocket, “is the only comfort we have in such long separations. Yes, I have one other comfort in his picture, but poor Edward has not even that. If he had but my picture, he says he should be easy. I gave him a lock of my hair set in a ring when he was at Longstaple last, and that was some comfort to him, he said, but not equal to a picture. Perhaps you might notice the ring when you saw him?”

“I did,” said Elinor, with a composure of voice, under which was concealed an emotion and distress beyond any thing she had ever felt before. She was mortified, shocked, confounded.

We too are mortified, shocked, and confounded, and we feel it deeply because these emotions are attached to a physical object. We thought the ring and the hair meant one thing, and to discover without a doubt that it means something else—this immediately evokes a reaction.

For me, this is the most powerful use of objective correlative in Sense and Sensibility, yet Austen continues to use locks of hair for emotional effect by bringing back the other lock of hair: Marianne’s.

When Marianne and Elinor spend the season in London, Marianne is snubbed by her love, Willoughby, and Elinor finds Marianne on her bed, completely and “violently” distraught. Next to Marianne, she discovers a letter from Willoughby, who has returned Marianne’s lock of hair.

It is with great regret that I obey your commands in returning the letters with which I have been honoured from you, and the lock of hair, which you so obligingly bestowed on me.

Marianne had asked for her letters and the lock of hair back, “if your sentiments are no longer what they were.” But she did not actually want him to return the hair. As she tells Elinor, she thought they were engaged:

“I felt myself,” she added, “to be as solemnly engaged to him, as if the strictest legal covenant had bound us to each other.”

“I can believe it,” said Elinor; “but unfortunately he did not feel the same.”

“He did feel the same, Elinor—for weeks and weeks he felt it. I know he did. Whatever may have changed him now, (and nothing but the blackest art employed against me can have done it), I was once as dear to him as my own soul could wish. This lock of hair, which now he can so readily give up, was begged of me with the most earnest supplication. Had you seen his look, his manner, had you heard his voice at that moment!”

Marianne rereads Willoughby’s letter, and the reference to the lock of hair only makes her more upset:

“It is too much! Oh, Willoughby, Willoughby, could this be yours! Cruel, cruel—nothing can acquit you….‘The lock of hair, (repeating it from the letter,) which you so obligingly bestowed on me’—That is unpardonable. Willoughby, where was your heart when you wrote those words? Oh, barbarously insolent!—Elinor, can he be justified?”

Once again, Austen employs objective correlative to show the depth of Marianne’s emotion by attaching it to a physical object. And, like Elinor, we feel deeply for Marianne.

Having built up this chain of events, with this set of objects (the locks of hair), Jane Austen continues to use them to great effect, bringing up each lock of hair one additional time.

When Marianne is severely ill and almost dies, Willoughby comes to visit, and tries to justify and redeem himself to Elinor. He blames his fiancé for forcing him to break Marianne’s heart and return Marianne’s lock of hair.

“[Marianne’s] three notes,—unluckily they were all in my pocketbook, or I should have denied their existence, and hoarded them for ever,—I was forced to put them up, and could not even kiss them. And the lock of hair—that too I had always carried about me in the same pocket-book, which was now searched by Madam with the most ingratiating virulence,—the dear lock,—all, every memento was torn from me.”

Elinor is tempted to absolve Willoughby—his speech is long and passionate, and the way he talks about Marianne’s lock of hair is definitely a point in his favor. Yet he returned it and broke his heart (and behaved like a rascal in other ways).

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing

https://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/69-Square.png

2160

2160

Katherine Cowley

http://www.katherinecowley.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Katherine-Cowley-1.png

Katherine Cowley2025-01-27 16:50:132025-01-27 16:50:14#69: The Jane Austen Approach to Critiquing Writing