#36: Use the Setting as a Character

In the past few weeks, we’ve talked about a number of concepts related to setting:

- Using description to establish a setting

- Using a distinctive setting for major plot turns

- Using setting to complement or contrast emotion

- Using familiar and invisible settings

- Using unfamiliar settings

- Establishing the character of a setting

Now, for the final post on setting, I want to address one final topic:

Using the setting as a character

I’ve seen some writers claim that every well-written setting is a character, but to me, making this argument is problematic: if every setting is a character, then the words “setting” and “character” cease to be useful—their meanings are conflated and it is more difficult to talk about their very really differences.

In most stories, the setting is not a character. This is true for most of Jane Austen’s work: her settings are interesting and profound, they reflect the character’s emotional states and sometimes the themes of her stories, yet they aren’t characters. Her settings have character, they have flavor, they mean something to the characters, and they impact the plot, but still they are not characters.

One of the Oxford English Dictionary’s definitions is useful in terms of how we use the word “character” in regard to stories:

Character, noun: “A person portrayed in a work of fiction, a drama, a film, a comic strip, etc.; (also) a part played by an actor on the stage, in a film, etc., a role.”

Ultimately, a character is a person, and ultimately, a setting is not.

Yet sometimes, a setting does act the part of a character; sometimes, a setting acts with personhood.

For instance, in “man vs. nature” stories (which includes everything from disaster stories to smaller, more individual stories like Hatchet), the setting does act as a character—but not just any character; here the setting acts as an antagonist, often virulent, actively fighting against the protagonist and their goals.

Yet you don’t have a sinister, oppositional setting for the setting to act as a character in the story.

In order for a setting to be a character it must:

- Play an active part in the story; be an actor.

- Impact multiple plot points throughout the story.

- Carry a larger metaphorical role that is present throughout the narrative, not just in one particular scene or section.

- Be vibrant like a living organism, and have the potential for change.

- Receive the sort of attention from characters that is normally reserved for people.

- Not be a manifestation of a single character or a small group of characters. (For this reason, Rosings would not be a character, because while it is important, it is entirely defined by Lady Catherine de Bourgh.)

A clear example of Jane Austen using setting as a character is in her uncompleted novel Sanditon. Sanditon is a changing, growing sea town that is attempting to grow into a destination, and it acts as a character in the story.

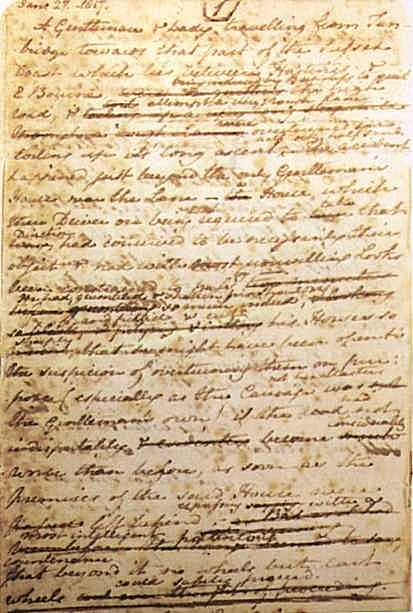

A page from the manuscript of Sanditon

One of the characters, Mr. Parker, describes Sanditon:

“Sanditon itself—everybody has heard of Sanditon,–the favourite spot of all that are to be found along the coast of Sussex;–the most favoured by Nature, and promising to be the most chosen by man.”

He goes on to say:

“Nature had marked it out—had spoken in most intelligible characters—the finest, purest sea breeze on the coast—acknowledged to be so—excellent bathing—find hard sand—deep water ten yards from the shore—no mud—no weeds—no slimy rocks—never was there a place more palpably designed by Nature for the resort of the invalid—the very spot which thousands seemed in need of—the most desirable distance from London!”

The narrator comments:

Sanditon—the success of Sanditon as a small, fashionable bathing place was the object for which he seemed to live….Sanditon was a second wife and four children to him—hardly less dear—and certainly more engrossing.

Sanditon is in a moment of transformation—it is growing, and how it will grow and develop and effect its inhabitants and its visitors is still unclear. The old is being discarded and the new sought for. Mrs. Parker sees the things that have been lost, the things she misses, the advantages of the old Sanditon, while Mr. Parker sees breaking from the past as a good thing:

“And whose very snug-looking place is this?” said Charlotte, as in a sheltered dip within two miles of the sea, they passed close by a moderate-sized house, well fenced and planted, and rich in the garden, orchards and meadows which are the best embellishments of such a dwelling. “It seems to have as many comforts about it as Willingden.”

“Ah!” said Mr. Parker. “This is my old house—the house of my forefathers—the house where I and all my brothers and sisters were born and bred—and where my own three eldest children were born—where Mrs. Parker and I lived till within the last two years—till our new house was finished….

“One other hill brings us to Sanditon—modern Sanditon—a beautiful spot.—Our ancestors, you know, always built in a hole.—Here were we, pent down in this little contracted nook, without air or view, only one mile and three quarters from the noblest expanse of ocean between the South Foreland and the Land’s End, and without having the smallest advantage from it. You will not think I have made a bad exchange when we reach Trafalgar House—which, by the bye, I almost wish I had not named Trafalgar—for Waterloo is more the thing now.”

Yet while Mr. Parker is leading many of the efforts to transform Sanditon, it refuses to be defined by him. It is talked of constantly by others, from Lady Denham to Sir Edward, and many actors have a role in its future, and its future will impact the fates of dozens of characters.

Mr. Parker clings to the idea of Sanditon on a track of forward progress, he holds to his expectations for it:

“Civilization, civilization indeed!….Who would have expected such a sight as a shoemaker’s in old Sanditon!—This is new within the month.”

Yet he cannot control it; it refuses to mold to his desires; it is separate from himself and what he wants for it:

It was emptiness and tranquility on the Terrace, the cliffs, and the sands. The shops were deserted, the straw hats and pendant lace seemed left to their fate both within the house and without, and Mrs. Whitby at the library was sitting in her inner room reading one of her own novels, for want of employment.

It is a place of tension, where even its number and type of inhabitants are outside of anyone’s control:

Mr. Parker could not but feel that the list [of families] was not only without distinction, but less numerous than he had hoped.

Andrew Davies’ television series Sanditon continues Jane Austen’s unfinished story. In the first season, Davies does an excellent job of making Sanditon a character. We see its growing pains, the troubles of the workers, money problems, and, in the final episode of the season, what begins as a minor problem within the setting becomes a major problem for the entire community. In Davies’ adaptation, the setting is constantly an actor in the story and the lives of the other characters.

Exercise 1: Read the article Ten Books Where the Setting is a Character. Find another example of a setting that is also a character. What makes the setting a character? Why is it useful for the story to have this setting as a character?

Exercise 2: Set a timer for twenty or thirty minutes and begin writing a flash fiction story (less than 1000 words) where the setting is a character. You could use your time to outline and develop ideas or to rush write the beginning of the story. If you the like the direction of focus of the story, take additional time to finish writing and revising it.

Exercise 3: Choose three settings that you have experienced in real life (cities, buildings, outdoor regions, etc.) that would make good candidates for being a character in a story. Make a list of each of their distinguishing attributes, and then add a few notes for what it would take for these to not just be a really compelling, cool setting, but also a character in a story.