#11: Use Exposition to Set the Stage

Soniah Kamal’s novel Unmarriageable, an incredible retelling of Pride and Prejudice in modern-day Pakistan, opens with Alysba Binat (our Elizabeth counterpart) teaching Pride and Prejudice at an English-speaking high school in Pakistan. In the beginning scene, she has her students—all female—write their own first lines inspired by the first line of Pride and Prejudice, their own “truths universally acknowledged.” As Alys leads the discussion, she brings up double-standards for men and women, explains that women’s independence is not a Western idea and has roots in their own culture, and raises the possibility that a woman’s sole purpose is not to marry and have children.

One of the ninth graders arrives late to class, a diamond engagement ring on her hand, and eventually the students turn the questions to Alys—why are you not married?

“Unfortunately, I don’t think any man I’ve met is my equal, and neither, I fear, is any man likely to think I’m his. So, no marriage for me.”

This scene sets up the core conflict of the novel—will Alys find her equal and eventually marry? It also sets up Alys’ personality, her quest to educate the young women of her community, and the cultural context in which she lives. In the first two chapters we also learn of her conflicts with the principal, information about her four sisters, how the family has lost their fortune and gotten into the financial straits that require the two oldest sisters to work, and we get a sense of the city and where it’s wealth and poverty are located. All this is so the stage is set, so that when the inciting incident disrupts Alys’ life and moves her on her journey (in the form of an invitation to a huge wedding where they will meet Bingla and Darsee), we as an audience are ready for it.

This is exposition, the setting of the stage for the story in order to provide important background information to the reader about the characters, their history, and their world.

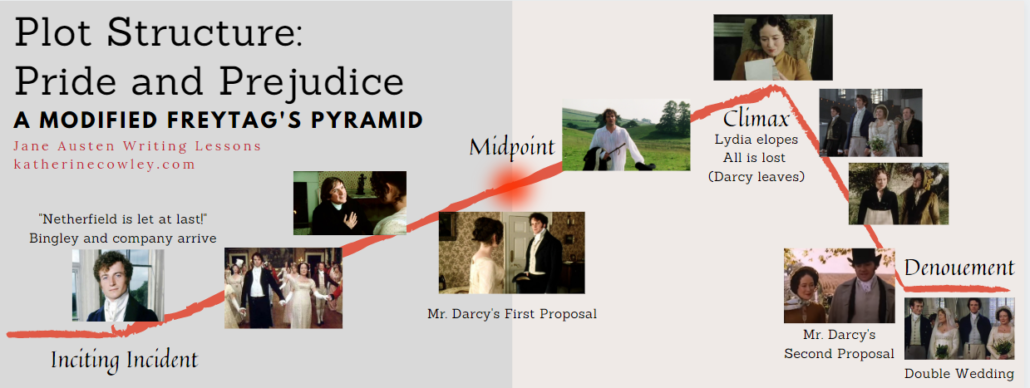

As discussed in the lesson on plot structure and external journeys, the exposition shows the world in stasis, and it requires the inciting incident to launch the external journey of the plot and the internal journey of character transformation.

According to Oxford Languages, the word exposition comes from the Latin verb exponere, which means to “expose, publish, [and] explain.”

exponere = to expose, to publish, to explain

Good exposition should:

The first four paragraphs of Jane Austen’s novel Emma provide the exposition for the story. We begin with the opening line:

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

This quickly paints an image of Emma’s character, her high place in society, and her general satisfaction with life.

In the second paragraph we learn the following, which brings up key details from Emma’s past and sets up the world and her place in it:

- Emma is the second daughter

- Her sister is married and gone

- She is mistress of the house (or basically, the female manager of it)

- Her father is “affectionate” and “indulgent”

- Her mother died when she was very young

- Her governess acted as a replacement mother figure in her life

That’s a lot for one two-sentence paragraph: Jane Austen manages to swiftly set the stage.

The third paragraph goes into more details on the governess, Miss Taylor, because these details will demonstrate the disruptiveness of the inciting incident:

- Miss Taylor has been with the family for 16 years

- She is more of a friend or sister figure than a governess

- She does not restrain or direct Emma (and has not for quite some time)

- “They had been living together as friend and friend very mutually attached, and Emma doing just what she liked; highly esteeming Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by her own.”

The fourth paragraph raises the themes and issues which will be explored throughout the story. In this case, it’s a look at the flaws in Emma’s character, and how these flaws will drive the narrative:

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself: these were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at present so unperceived, that they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.

By the time we reach the fifth paragraph, all the essential details have been explained, and we are prepared for the inciting incident: Miss Taylor’s marriage.

We learn plenty of other details of backstory as the novel progresses—details about the past and about Emma’s relationships with others in her community—but these are not included in the initial exposition, because they are not essential for setting the stage.

Sometimes exposition—this setting of the stage for the reader—takes several chapters, as in the example of Unmarriageable. Other times, it takes a few paragraphs, such as in Emma. The next lesson will discuss stories that start in medias res, at the moment of the inciting incident, or sometimes even after the inciting incident, and address how exposition can be incorporated in small amounts as the story progresses.

Regardless of the manner in which the exposition is presented, it sets the stage for the story and orients the reader.

Exercise 1: In the beginning of Emma, Jane Austen uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. She sets forth the character, the world, and the situation through the perspective of a storyteller introducing her cast. The narrator is insightful and interesting, and is unafraid to comment on her characters and their attributes.

Brainstorm a new character by choosing and name and writing down three of their defining characteristics, attributes, or interests.

Set a timer for 15 minutes, and draft a brief exposition which uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. This should set the stage for the character and their world.

Exercise 2: In Unmarriageable, Soniah Kamal uses a close third person point of view. She includes the same sort of expository details as Austen does in Emma, but she reveals them through use of a scene. (Jane Austen does uses this approach—providing exposition through a scene—in some of her novels.)

Use the same character and characteristics/attributes/interests from exercise 1. Instead of sharing these details from a storyteller perspective, figure out how to reveal these details organically through a scene—have these demonstrated through the character’s actions or interactions. Set a timer for 15 minutes and write an opening scene that provides exposition.

Note: providing exposition through a scene is currently the most common approach in writing, though there are books still being published that open with the perspective of a storyteller setting the stage.)

Exercise 3:

Option 1: For a new story, brainstorm elements that may be useful for include in the exposition.

- Who is the main character?

- What about the character’s past informs who they are today?

- Who are the other key characters?

- What do readers need to understand about the world?

- What themes or issues could be raised that will be explored throughout the story?

- What details about the character and the world could be included in the exposition that will contrast and show the disruptiveness of the inciting incident?

Once you have brainstormed, consider what absolutely must be revealed in the exposition, and what can be revealed later. Most details about the character and the world can be revealed, piece by piece, later in the story, so choose what is both the most essential and the most interesting way to take us into the world and the perspective of the main character.

Option 2:

If you have already drafted a story, analyze what you included as part of the exposition. Label each detail with categories that could include things like “character attribute,” “character history,” “supporting character,” “relationship,” “worldbuilding,” “theme,” etc. Are there any details that could be saved for later in the story? Are any details that are missing that would demonstrate how the character’s world is disrupted by the inciting incident?