Posts

#21: Reveal Characters Through Tension

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

There are countless blog posts and books which give step-by-step guides on how to create a good first impression. In stories too, characters have first impressions of each other which can have a huge impact on their relationships and the plot (the original version that Jane Austen wrote of Pride and Prejudice was actually titled First Impressions.)

Yet another way to think about first impressions is the first impressions that characters leave on the reader. Whether a character is major or minor, whether they are introduced at the beginning of the book or near the end, our first impressions of characters begin the process of revealing them to us.

Revealing Characters to the Reader

But how do you reveal character, and how, as a writer, do you make sure that you leave the right first impression on readers? (Unlike in meeting people in real life, in a novel the goal is not necessarily to leave the best first impression, but rather, a first impression that helps us understand the essence of someone’s character, and often foreshadows their journey or the role that they will play in the story.)

One of the fastest ways to truly know someone is to see what they do and how they act in moments of struggle or tension. It is these moments that often draw out or reveal true or fundamental character. (I remember receiving very similar dating advice—you want to make sure that you see the person you are dating in hard or challenging situations, not just good ones.)

In Northanger Abbey, the narrator introduces us to Catherine Morland in the first chapter, but the first time we see Catherine Morland in scene rather than summary is in Chapter 2.

Catherine has just arrived in Bath, where she is staying with her friends, Mr. and Mrs. Allen. They go to a public ball, and unfortunately, they do not know anyone. Mr. Allen immediately goes off on his own, leaving Catherine and Mrs. Allen to fend for themselves.

Gif from the 1987 film adaptation of Northanger Abbey

“How uncomfortable it is,” whispered Catherine, “not to have a single acquaintance here!”

“Yes, my dear,” replied Mrs. Allen with perfect serenity, “it is very uncomfortable indeed.”

“What shall we do?—The gentlemen and ladies at this table look as if they wondered why we came here—we seem forcing ourselves into their party.”

“Ay, so we do.—That is very disagreeable. I wish we had a large acquaintance here.”

“I wish we had any;–it would be somebody to go to.”

Jane Austen has efficiently and effectively revealed key elements of Mrs. Allen’s and Catherine’s characters.

First, Mrs. Allen:

- Mrs. Allen does not take action, even when she sees that her companion, who is relying on her to take the lead, is uncomfortable.

- She has “perfect serenity” which can either demonstrate a great Zen state and that she is not bothered by outside influences and struggle—or this could demonstrate a lack or failing on her part.

Next, Catherine:

- Her wants are revealed—she wants to know people, she wants to dance and have a good experience, she wants to feel comfortable in her surroundings.

- She is currently more passive than active. She lets others control or dictate her actions (which is something that will become an important plot point later).

- She is a sympathetic character, an underdog, and we want her to succeed.

- She is concerned about propriety and her place in society. While one of the things Catherine must learn over the course of the novel is how to read people and situations, she isn’t starting from nothing.

Later in the scene, near the end of the ball, Mr. Allen returns:

“Well, Miss Morland,” said [Mr. Allen], directly, “I hope you have had an agreeable ball.”

“Very agreeable indeed,” she replied, vainly endeavouring to hide a great yawn.

This brief exchange reveals more about Catherine:

- She is more open with Mrs. Allen than Mr. Allen

- Mr. Allen is unaware of the situation

- She is kind and considerate. She is not a complainer or whiner, and tries to put a good spin on things, even as she fails to suppress a yawn. This is endearing and makes her more sympathetic.

- The chapter closes with everyone leaving, and with Catherine’s attempt to frame her own experience:

She was looked at, however, and with some admiration; for, in her own hearing, two gentlemen pronounced her to be a pretty girl. Such words had their due effect; she immediately though the evening pleasanter than she had found it before—he humble vanity was contented—she felt more obliged to the two young men for this simple praise than a true quality heroine would have been for fifteen sonnets in celebration of her charms, and went to her chair in good humour with everybody, and perfectly satisfied with her share of attention.

This paragraph is brilliant, because Catherine begins this scene with struggle: she is stressed and worried, and yet this final paragraph shows that she is not one to be crushed.

Catherine is both naïve and optimistic, inexperienced and loveable. In just this short scene, Austen has managed to set up some of the core tensions that make Catherine a three-dimensional character whose story is worth following.

One of the biggest advantages of using a moment of tension or challenge to reveal character is that is demonstrates characters’ strengths and weaknesses, and it sets the stage for the tools and limitations that will accompany them on their journey. As characters are pushed and pulled by outside and inside forces, we see what they are really made of.

Struggle or tension can manifest in numerous forms, including:

Two characters wanting different things

A small or large problem

A lack or a need that is manifest in a particular situation

A change in situation that tests or challenges a character

A goal or task which is challenging and requires effort

These scenes are effective not just for the first time we meet a character, but throughout the story. If you want to show a character’s change or growth, then do it in a scene that has tension or struggle.

Sometimes you may also want to intentionally write a character that has given of a false first impression to the reader, that disguises their true character (even while containing hints of it). In this case, have moments of tension later that reveal their true character to the reader.

Exercise 1: Choose a novel or short story and print a copy of the first moment of tension, struggle, or challenge for the character. Now, find and print a copy of the last big moment of tension or struggle for this character in the novel (this is often but not always during the climax).

Mark up these scenes, underlining and annotating with what reveals character (wants, needs, multidimensional, strengths/weaknesses, active/passive, sympathetic/unsympathetic). Compare these scenes and how the character has changed throughout the course of the novel. How does the first scene of tension and struggle set up the final scene of tension and struggle?

Exercise 2: Jane Austen is a master of creating tension and struggle from small, everyday moments, and using this tension to express and develop character. List five everyday objects from the same category (i.e. kitchen items, toys, technology, apparel). Write a short scene which includes at least two of these objects and which also uses tensions and struggle to reveal character.

Exercise 3: If you have a draft of a short story or novel, analyze what types of tension you use throughout the story. Is the tension or struggle manifested by:

- Two characters wanting different things

- A small or large problem

- A lack or a need that is manifest in a particular situation

- A change in situation that tests or challenges a character

- A goal or task which is challenging and requires effort

- Other

Do the sorts of struggles shift over the course of your novel? How does this affect the main character’s inner journey? Is the progression satisfying?

#13: Start the Story Early (If Necessary)

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

Most stories start not long before the inciting incident, providing a brief description, moment, scene, or a few chapters which encapsulate the period BEFORE—before everything changes for the characters. Emma and Persuasion provide good examples of this.

Other stories, like Pride and Prejudice, start after the inciting incident—in medias res.

Yet other stories take a very different approach to exposition and start long before the inciting incident disrupts the story (note that starting long before the inciting incident does not necessarily mean that the telling of the exposition needs to be long—expositions that start early can still be brief). Jane Austen uses this technique in two of her novels: Northanger Abbey begins at Catherine Morland’s birth, and Mansfield Park begins years before Fanny Price is born.

These two novels start the exposition early for two different purposes:

- Northanger Abbey: To show the main character’s life trajectory, and to contrast the inciting incident (and what comes as a result) against the character’s entire life.

- Manfield Park: To demonstrate a prior formative moment which caused a drastic shift in the main character’s life, and created a new normal, which is then disrupted by the inciting incident.

Life Trajectory in Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey demonstrates the main character’s life trajectory prior to the inciting incident. The novel begins with the line:

No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would have supposed her born to be an heroine.

After this establishment of theme (and the delightful, rather satirical approach of the entire novel), we learn of Fanny’s birth:

Her mother…had three sons before Catherine was born; and instead of dying in bringing the latter to the world, as anybody might expect, she still lived on—lived to have six children more…

We follow Catherine Morland’s childhood, learning that she prefers cricket to dolls, seeing her disinterest in learning and watching her quit music after only a year or instruction. The narrator jumps from Catherine at age ten to age fifteen, and we see her continued development:

To look almost pretty is an acquisition of higher delight to a girl who has been looking plain the first fifteen years o her life, than a beauty from her cradle can ever receive.

Catherine reaches seventeen, with nothing to interrupt the path that she is on, a point that the narrator draws attention to:

She had reached the age of seventeen, without having seen one amiable youth who could call forth her sensibility; without having inspired one real passion, and without having excited even any admiration but what was very moderate and very transient. This was strange indeed!

All this in the first chapter. By creating a life trajectory, it establishes a shared set of reference points with the reader, reference points that help us understand the main character and who she is prior to the inciting incident. These references are essential, because without them, we would be unable to understand Catherine’s choices throughout the novel—her life trajectory informs her naivety, her desire to be liked, her fascination with new people and places, and how she constantly turns to books as an escape.

The last paragraph of the first chapter establishes the inciting incident, which is placed in direct contrast with the main character’s life to this point:

[Mrs. Allen], a good-humoured woman, fond of Miss Morland, and probably aware that if adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad, invited her to go with them.

The other benefit of this approach to exposition is that it allows the narrator to avoid infodumps later—it would be difficult to include all of these details as backstory later in the story without unnaturally piling them on.

The elements included in Northanger Abbey are referred to again and again throughout the story, both directly and indirectly. By journeying with Catherine from her birth to age 17, we are prepared for the much bigger journey she will take throughout the novel.

Prior Formative Moment/Shift in Mansfield Park

While the exposition of Mansfield Park covers a lot of ground, the main purpose is for us to experience a formative moment, a huge shift, in Fanny Price’s early life.

Manfield Park starts before Fanny’s birth, and focuses on the weddings of the prior generation. Three sisters become, respectively, Lady Bertram, Mrs. Norris, and Mrs. Price. Mrs. Price is the one whose marriage has disappointed her family by being beneath her station. Mrs. Price loses contact with her family, and only reestablishes it when expecting her ninth child. At this point, her oldest daughter, Fanny, is nine years old, and is about to experience a cosmic shift, caused by her aunts, Lady Bertram and Mrs. Norris, and her uncle, Lady Bertram’s husband, Sir Thomas.

Mrs. Norris was often observing to the others, that she could not get her poor sister and her family out of her head, and that much as they had all done for her, she seemed to be wanting to do more: and at length she could not but own it to be her wish, that poor Mrs. Price should be relieved from the charge and expense of one child entirely out of her great number. “What if they were among them to undertake the care of her eldest daughter, a girl now nine years old, of an age to require more attention than her poor mother could possibly give? The trouble and expense of it to them, would be nothing compared with the benevolence of the action.” Lady Bertram agreed with her instantly. “I think we cannot do better,” said she, “let us send for the child.”

Sir Thomas is initially resistant the idea but is won over by his sister-in-law and wife. As the scene continues, we come to understand the character of these three adults, and without having met Fanny, we know intuitively that this is not going to be a warm, welcoming place for her.

We meet Fanny in Chapter 2, as she begins her “long journey.” We are with her throughout this epic change; we feel her discomfort as she is introduced to the family, and we see into her mind and character:

Her consciousness of misery was therefore increased by the idea of its being a wicked thing for her not to be happy.

Fanny struggles on and on. Through her eyes, we see how inferior she feels compared to her cousins, and how unrefined. In this exposition, we also come to know, in more depth, one of the other key characters of the novel, Edmund Bertram.

A week had passed in this way, and no suspicion of it conveyed by her quiet passive manner, when she was found one morning by her cousin Edmund, the youngest of the sons, sitting crying on the attic stairs.

“My dear little cousin,” said he, with all the gentleness of an excellent nature, “what can be the matter?”

A touching scene follows in which Edmund helps Fanny share her thoughts. He comes to learn about her family and her relationships with her siblings. He also helps her write and send a letter, promising she will not have to pay for it. This first real moment between Edmund and Fanny sets up their entire relationship, which is such a huge part of the novel, and it is better experienced in scene rather than through summary or flashback.

Thus, in chapter 2, we experience this great upheaval in Fanny’s life, and we see her adjust to the new normal, the new status quo.

If there has been a formative moment, a grand shift in a character’s life, there is power in allowing the reader to experience it with the main character. If this sort of shift merits being part of the exposition, it is typically large enough that in a different story it could be the inciting incident. Yet if used as exposition, it establishes a new normal, which is then disrupted by the inciting incident.

If Fanny’s removal to Mansfield Park was the inciting incident, the novel would be about ten-year-old Fanny and the internal and external journey she takes as she adjusts to her new life. Instead, this adjustment is covered in a single chapter, paving the way for the actual inciting incident, which is Mr. Norris’ death and the arrival of a new set of rather disruptive characters: Mr. and Mrs. Grant, Mr. Crawford, and Miss Crawford. These new characters disrupt not just Fanny’s life, but the lives of the entire family. But for Fanny, this disruption, this inciting incident, feels deeper, because this is not the first huge disruption she has experienced.

In Conclusion

In Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park, Jane Austen uses two of the major approaches for starting a story early: providing a life trajectory, and depicting a prior formative shift. Yet starting the story early is not the only good approach to exposition, nor should it be the default. In Persuasion there are several formative shifts for Anne prior to the start of the novel—her mother’s death and her short-lived engagement. Yet Anne’s experience of these moments is revealed effectively through backstory, and in fact, their placement later in the story serves to reveal Anne’s character and her regrets at key moments.

If you want to start the story early, there needs to be a good reason for us to experience these scenes with the character. This experience should be enlightening to us, and, like in Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park, there needs to be a reason that they must be experienced at the beginning. We should start our stories early if it helps us understand the logic of everything else.

Exercise 1: Find another story—a book or a film—that starts early. Now analyze it. Is it painting a character trajectory? Is it showing a prior disruptive moment? Or is it doing something else entirely?

Exercise 2: Take one of your characters (or an idea you have for a character) and write a 500-word life sketch, that begins either before or at their birth. Once you’re finished, analyze the results:

- What new things did you learn about your character?

- What were the biggest, most defining moments in your character’s early life? What shaped them into who they are as they enter the story?

- Are there elements of your character’s early that should be woven into the story as backstory? Or is this a case where it would be useful to experience the character’s early life as part of the exposition?

Even if none of the life sketch is incorporated into the story, writing it is a useful practice that can help you understand your character, their personality, and their choices.

Exercise 3: Take a fairy tale or classic story that does not give many specific details about a character’s younger years (for example, Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice). Brainstorm specific events and incidents that could have occurred before the start of the story, and would be in keeping with their character, the story world, and what we do know.

#6: Use a Character Arc to Make Your Character Change and Grow

/0 Comments/in Jane Austen Writing Lessons/by Katherine Cowley

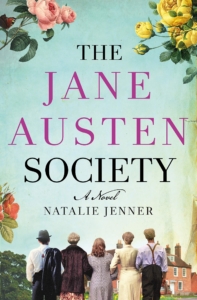

The Jane Austen Society by Natalie Jenner is a beautiful new novel about how our favorite authors can save us. It made me cry approximately three times—fine, exactly three times—and is a fabulous read. In the novel, the first character we meet is the farmer Adam Berwick, a man broken by loss of family and dreams. The book begins with him in a death-like pose next to the Chawton cemetery, yet over the course of the first chapter he changes and grows.

Adam is challenged by a visitor to the town to read Jane Austen, and he reluctantly agrees. As he reads Pride and Prejudice, he begins to change:

Reading Jane Austen was making him identify with Darcy….It was helping him understand how even someone without much means or agency might demand to be treated. How we can act the fool and no one around us will necessarily clue us in.

He would surely never see the American woman again. But maybe reading Jane Austen could help him gain even a small degree of her contented state.

Maybe reading Austen could give him the key.

The external plot of the story is Adam and others coming together to save Jane Austen’s Chawton home. But each of the characters, including Adam, undergoes internal change and transformation over the course of the novel.

In a novel, the internal journey, or character arc, constantly intersects with the external journey. A character arc is not a straight line of progress. It includes failures and successes, embracing and resisting change. Ultimately though, our characters should learn and grow. (I have the same hope for my children. So far it’s working, except for the fact that my youngest has been coloring on walls for years.)

As you create a character arc, consider how this arc is influenced by:

What happens to the character

The choices and decisions made by the character

Moments of resisting change and moments of progress

Who the character needs to become by the end of the novel

All of Jane Austen’s completed novels contain excellently crafted character arcs: all of her main characters change, develop, and transform over the course of their stories.

One example of this is Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey. In the introduction to the Broadview edition of Northanger Abbey, the scholar Claire Grogran writes about Catherine’s transformation: “Catherine becomes an adept reader not only of texts but also of people and of situations.”

An illustration of Catherine Morland reading.

This illustration, by an unknown artist, was included in the 1833 Bentley Edition of Jane Austen’s Novels.

At first, Catherine is innocent and naïve, which allows her to be manipulated by others, including her friend, Isabella Thorpe, and Isabella’s brother, John Thorpe. Even though John consistently interferes with her desires and other friendships, she does not see him for who she is.

The first time Catherine meets John Thorpe, she is “fearful of hazarding an opinion of [her] own in opposition to that of a self-assured man.” She finds herself constantly frustrated by Thorpe’s speech and behavior, yet she distrusts her own judgment, and does not read anything truly wrong into his character:

These manners did not please Catherine; but he was James’ friend and Isabella’s brother; and her judgment was further brought off by Isabella’s assuring her, when they withdrew to see the new hat, that John thought her the most charming girl in the world.

As their relationship progresses, Catherine consciously makes the decision to not read into his character, to ignore his flaws, and to allow him to override her plans. In this, she is resisting change and development. (Characters often resist change because change is hard.)

Little as Catherine was in the habit of judging for herself, and unfixed as her general notions of what men ought to be, she could not entirely repress a doubt, while she bore with the effusions of his endless conceit, of his being altogether completely agreeable.

Yet because of this, she misses the opportunity to spend time with her friend Miss Tilney, and her brother, Mr. Tilney, who she is romantically interested in. This leads her to conclude that “John Thorpe himself was quite disagreeable.”

A few chapters later, Catherine plans a walk with Miss Tilney, but it happens to be at the same time as an outing that John Thorpe wants Catherine to attend. Jealous and vindictive, Thorpe ignores Catherine’s wishes, goes to Miss Tilney, and cancels Catherine’s walk.

When Catherine learns of this, she takes action in a way that begins her path towards transformation and growth: she decides to trust her own judgement of the people and the situation, and to act decisively. Disregarding all of Isabella’s and John’s entreaties, she declares,

“This will not do. I cannot submit to this. I must run after Miss Tilney directly and set her right.”

Catherine then proceeds to do so. Throughout the rest of the novel, she gains more practice reading people and situations. Sometimes her judgment leads her false (as when Henry finds Catherine in his mother’s room, looking for clues of her supposed murder), but over the course of the novel she does improve in her ability to read situations and she allows this reading to inform and change her behavior.

Exercise 1:

Pick a name for a character, any name.

Now choose one of the following attributes:

- Courage

- Willingness to sacrifice for others

- Ambition

- Persistence

- Resourcefulness

- Thriftiness

- Ability to forgive others

Set a timer for ten minutes, and in that time make a list of the following four events which would create a basic character arc for this character:

- An event which shows that the character does not yet possess this attribute

- An event which shows the character learning this attribute

- An event which shows the character resisting or failing at the implementation of this attribute

- An event which shows that the character has learned to incorporate this attribute into their lives

Exercise 2:

Read a book or watch as movie, and as you do so, take notes on the main character. How do they change over the course of the story? What do they learn and how do they develop? How do they resist change? On a piece of paper, plot out the main points of their character arc. Visually, what type of line or arc would you draw to show their development?

Exercise 3:

Take a story of your own that you are currently writing or revising. Write a 2-3 sentence description of who the character must become by the end of the story. Then write a 2-3 sentence description of who the character is at the start of the story.

Now evaluate your character. A few things to consider:

- There needs to be enough distance between who the character is at the beginning of the story and who the character is at the end. In a novel, this distance will need to be much greater than in a short story.

- The character may have multiple things they need to learn.

- If your story is part of a series, the character needs to change or develop in new ways in each book.

- As the character develops and grows, the goal is not to make them a “perfect” character or eliminate all of the negative attributes that are a core part of their character.

- Often, more than one character has a character arc, and these arcs can intersect with each other, parallel each other, or interfere with each other.