#32: Use Setting to Complement or Contrast Emotion

In the last lesson, I discussed the advantages of using a distinctive setting in a major plot turn. In addition to assisting the plot, a setting is one of the most powerful ways to reveal a character’s emotions.

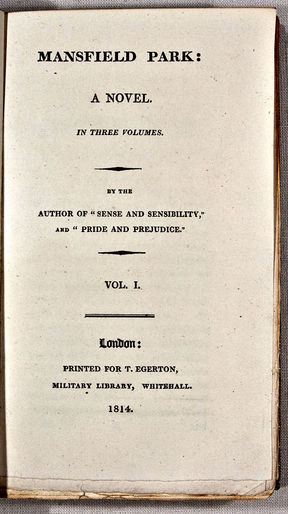

In Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park, the main character, Fanny Price, lives with her aunt and uncle and cousins. Fanny is often mistreated and ignored, but when her cousin Maria is married, both of Fanny’s female cousins—Maria and Julia—travel to London. Everyone’s treatment of Fanny improves, and she becomes a more essential and more valued part of the household.

Her friendship with a neighbor, Miss Crawford, also increases. One day, while Fanny is visiting Miss Crawford, the two are walking around the shrubbery at the parsonage, and they stop to sit on a bench. They are both in the exact same setting at the exact same time, but they both engage with it differently, and how they engage and interact with the setting provides insight into their emotions:

“This is pretty—very pretty,” said Fanny, looking around her as they were thus sitting together one day: “Every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with its growth and beauty. Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing; and now it is converted into a walk, and it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or an ornament; and perhaps in another three years we may be forgetting—almost forgetting what it was before. How wonderful, how very wonderful the operations of time, and the changes of the human mind!”

Fanny not only notices the growth and development of the setting, but she also eloquently expresses her observations. For the reader, Fanny’s musings on the shrubbery are not just a matter of an improved landscape: her musings reflect on how Fanny prefers her new role within the world. Previously, her family “never thought of [her] as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing,” but like the shrubbery, she is now flourishing. And because she is flourishing, she notices the shrubbery.

On the contrary, this is Miss Crawford’s reaction:

Miss Crawford, untouched and inattentive, had nothing to say.

Miss Crawford is naturally less interested in nature, but this character difference is not the full story. In the subsequent paragraphs, it begins to become clear that Miss Crawford is wrapped up in her own thoughts and reflections, as she tries to figure out what her future will look like. She is not a viewpoint character in this scene, yet still we glimpse her emotions by the very fact that she does not notice the setting and is unable to respond to Fanny’s enthusiasm.

Complements and Contrasts

When using setting to reveal emotion, the writer can:

In the above example, the emotion was revealed through speech, action, inaction, and awareness, all of which related or were in reference to the setting. Another effective method of revealing emotion is through the description of setting within the narrative.

Using the Setting to Complement Emotions

In Mansfield Park, Fanny’s uncle Lord Bertram becomes angry with her when she refuses an offer of marriage. He sends her back to her parents, which puts her in a setting that she has not interacted with since she was a young girl. How she feels about this is made clear by the narrator’s insights into her perception of the setting:

She was then taken into a parlour, so small that her first conviction was of its being only a passage-room to something better, and she stood for a moment expecting to be invited on; but when she saw there was no other door, and that there were signs of habitation before her, she called back her thoughts, reproved herself, and grieved lest they should have been suspected.

Several chapters focus almost entirely on Fanny’s interaction with the setting. The setting is not just her parents’ house; the setting is also the people in it (all of her many siblings, most of who she has no connection to), as well as and the behaviors and expectations associated with the house. In one passage, we read:

But though she had seen all the members of the family, she had not yet heard all the noise they could make.

Austen goes on to describe, in great detail, the hustle and bustle and the yelling and the arguing,

the whole of which, as almost every door in the house was open, could be plainly distinguished in the parlour, except when drowned at intervals by the superior noise of Sam, Tom, and Charles chasing each other up and down stairs, and tumbling about and hallooing.

Fanny was almost stunned. The smallness of the house, and thinness of the walls, brought every thing so close to her, that, added to the fatigue of her journey, and all her recent agitation, she hardly knew how to bear it.

There is never a need for Austen to state, “Fanny was not happy with this move and did not feel comfortable with her family. She felt unloved and unwanted.” None of these things need to be said, because we experience through it as Fanny experiences the setting. At the end of one of the chapters, the narrator does state Fanny’s emotions more directly:

In a review of the two houses, as they appeared to her before the end of a week, Fanny was tempted to apply to them Dr. Johnson’s celebrated judgment as to matrimony and celibacy, and say, that though Mansfield Park might have some pains, Portsmouth could have no pleasures.

However, this more direct statement of emotion works because of the artistry of it, because it is a direct revelation of Fanny’s internal thoughts, and because this direct statement of emotion has been earned. We have already experienced the emotion with Fanny by experiencing the setting with her. And so when this statement is made, we agree with her and we feel for her.

Using the Setting to Contrast Emotions

At other times, it can be effective to use the setting to provide a contrast to the character’s emotions. A good, beautiful day could be contrasted with a character’s depressions, just as a terrifying storm could contrast with a character’s happiness.

Near the beginning of the novel, when a young Fanny arrives at Mansfield Park, the wonderful, grand house provides a clear contrast to her emotions, actually serving to make her feel worse:

The grandeur of the house astonished, but could not console her. The rooms were too large for her to move in with ease; whatever she touched she expected to injure, and she crept about in constant terror of something or other; often retreating towards her own chamber to cry.

When a positive setting contrasts with a negative emotion, it can serve to alienate the character from their surroundings, as occurs in this example. This can make the character’s negative emotions feel even weightier to the reader. When a negative setting contrasts with a positive emotion, the character seems to transcend their setting. This can make the character’s positive emotions seem greater or more powerful to the reader.

Using the Setting Both to Complement and Contrast Emotions

Some settings both complement and contrast emotions. This can occur over the course of a novel, as a character’s relationship with the setting changes.

This can also occur within a single scene. When a setting both complements and contrasts emotions in a single scene, it often serves to highlight the complexity of human emotion as well as our nuanced experiences with our surroundings.

The following passage in Mansfield Park occurs when Fanny is still at her parents’ home. She is dreading receiving bad news in the mail. Note how the narrator calls attention to the fact of what the bright sunlight should do versus what it actually does, and how this transitions to Fanny noticing aspects of the setting which reflect her discomfort (such as the low-quality blue milk with motes and the increasingly greasy butter and bread):

The sun was yet an hour and half above the horizon. She felt that she had, indeed, been three months there; and the sun’s rays falling strongly into the parlour, instead of cheering, made her still more melancholy, for sunshine appeared to her a totally different thing in a town and in the country. Here, its power was only a glare: a stifling, sickly glare, serving but to bring forward stains and dirt that might otherwise have slept. There was neither health nor gaiety in sunshine in a town. She sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust, and her eyes could only wander from the walls, marked by her father’s head, to the table cut and notched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca’s hands had first produced it.

A bright cheery day is now a curse for Fanny—she normally loves the sun, but not now. Not in this context of this setting, and not in this context of her own emotional agony. The sun contrasts with her emotions until it is subverted into complementing her negative emotions.

In Conclusion

Just as Jane Austen does, we can use the setting to reflect or contrast with a character’s emotions. Often, this is more effective than just stating the emotion, and it allows the setting to perform work on multiple levels of the novel.

Exercise 1: One Setting, a Multitude of Possible Emotions

Photo by Mario Cuadros from Pexels

A single setting could be described in very different ways, depending on the character’s emotion. Consider the above photograph. Now write three short descriptions of the character within this setting, each which conveys a different emotion. Aim for a one to four sentence description, and choose from the following emotions:

- Fear

- Excitement

- Resignation

- Love

- Fatigue

- Concern for someone else

Exercise 2:

Choose a novel. Now find three different points in the novel which describe the setting while providing insight into emotion. Does the setting complement or contrast the emotion? Does it do both? What specific word choice and sentence structure helps produce the desired emotion?

Exercise 3:

Option 1: As you write a scene, consciously include details about the setting which either complement or contrast with the character’s emotions.

Option 2: Take an early draft of a scene you have written and revise it, focusing on using the setting to shine a light on the character’s emotions.