#18: Use Passive Characters Effectively

In Pride and Prejudice, Charlotte Lucas makes the decision that Elizabeth refuses: she marries Mr. Collins. Molly Greeley’s recent novel, The Clergyman’s Wife, is a compelling story which features Mrs. Charlotte Collins three years later. Charlotte is rather unhappy in her marriage, and begins the story as a rather passive character: she suffers in silence, she struggles to know what to write in her letters to Elizabeth, and she follows the edicts of Lady Trafford and Mr. Collins.

Mr. Collins has never visited or shown real concern for those living in his parish, and neither has Charlotte. But Charlotte decides she wants to change—she decides she wants to do something for those around her, so she visits the elderly Mr. Travis, and then the solitary Mrs. Fitzgibbon. As a result of her visits, Charlotte is criticized by both her husband and Lady Catherine. Yet Charlotte holds her own, and justifies her actions in a way that does not allow them to prevent them in the future.

The look Lady Catherine bestows upon me puts me in mind of the looks she used to give Elizabeth, when my friend dared to speak her true thoughts to her ladyship upon visiting me in the early days of my marriage.

Charlotte’s action is small but it feels heroic, and it shifts her from being a rather passive character to becoming a more active one.

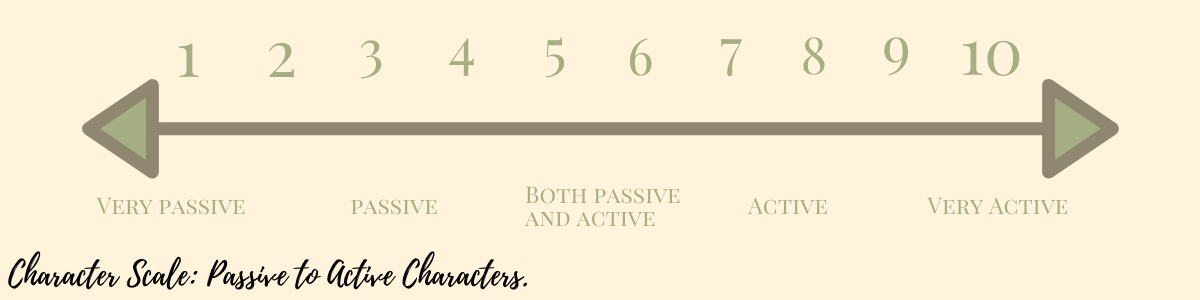

As discussed in the previous post on active characters, there is no true dichotomy between active and passive characters, but rather, it is a spectrum, and many characters shift to different points of this spectrum throughout the course of the story. At times it may even be useful to keep a character relatively passive for the entire story.

Yet choosing to write a passive character—whether for a portion or the entire novel—is challenging: it is easier to effectively write an active character than a passive one, because interest and empathy is automatically given to active characters, and must be gained in other ways by passive characters.

Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park features a generally passive character: Fanny Price.

As a young child, Fanny is brought to live with her aunt and uncle, the Bertrams, at Mansfield Park. Now that she is older, the Bertrams decide Fanny will live her terrible Aunt Mrs. Norris. Fanny is surprised, and this reaction shows, but she does nothing to try to change her situation. She complains a little to her one confidant, her cousin Edmund, but she does nothing active to change her fate. She is saved by outside forces: Mrs. Norris does not want her.

Later, the old horse she uses for exercises dies. This is something that happens to Fanny, and Fanny does nothing—in fact, because of her precarious situation as someone who has been taken in by the family, there is nothing she can do without risk of losing her home.

Edmund eventually notices what this loss has done to Fanny, and he takes it upon himself to put things to right. He is the active character in this situation, not Fanny.

1908 illustration of Fanny Price by C.E. Brock (in public domain)

After the arrival of the Grants and the Crawfords in the area, the narrator even comments on Fanny’s passivity:

And Fanny, what was she doing and thinking all this while? and what was her opinion of the new-comers? Few young ladies of eighteen could be less called on to speak their opinion than Fanny.

The number of people who claim Mansfield Park as their favorite Austen novel is a smaller number than those who love her other novels, and many readers find Mansfield Park a challenging book to read. I would argue that this is in part because Fanny is a passive character for much of this novel, and this makes it less accessible for some readers. Fanny also does not have a strong, forward-moving want or desire: at the beginning of the novel, Fanny wants to be left alone—she wants peace. And she does not take decisive actions to achieve this. Yet the novel is brilliant on so many levels, and Fanny’s character is an essential aspect.

In general, readers like forward motion and are drawn to characters with strong desires who reach for them. Readers can lose patience if it feels like the characters or the story is stalled.

One approach is to make passivity a part of the journey, as Molly Greeley does in The Clergyman’s Wife. By page fifty, Charlotte has taken a number of steps to being more active.

In Mansfield Park, it is much longer before Fanny becomes an active character, yet Austen uses other techniques to maintain interest and forward movement.

One of the ways Austen does this is by making Fanny’s character needs so great. At the beginning of the novel, some of Fanny’s basic survival needs are not being met: the Bertrams do not even allow her a fire in her rooms during the winter. (I am still pretty angry at Fanny’s relatives for this!) She also needs basic security: at any point, she knows that she could be thrown out of her home without warning, and this is threatened by her aunt Mrs. Norris even when Fanny expresses distaste for acting in a play.

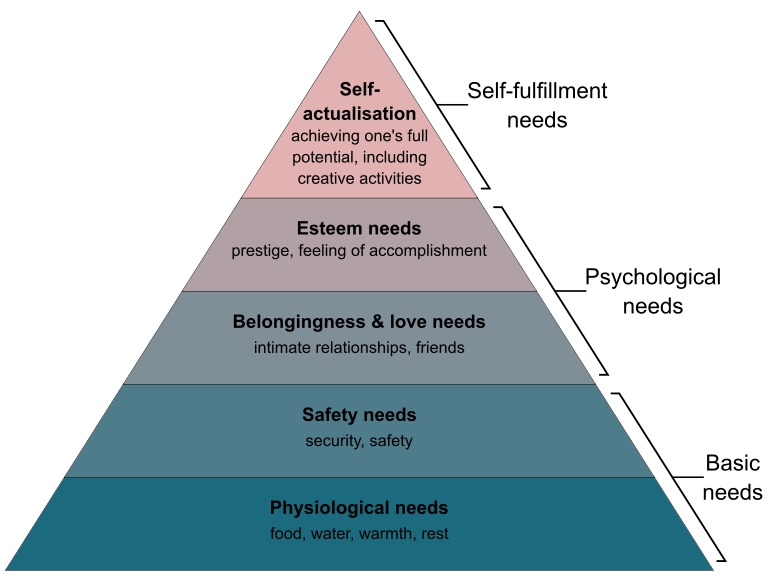

If we move further up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which I discussed in lesson 15, Fanny’s needs continue. Her psychological needs are great: she needs kindness, she needs acceptance, she needs friendship. (At the start of the novel, Edmund is her one friend, but plenty of his behaviors throughout the novel cause her further anxiety). Finally, Fanny needs love.

Fanny’s needs create sympathy from the reader: we want her situation to improve.

In the long-running (and Hugo award-winning) podcast Writing Excuses, author Brandon Sanderson talks about an approach to characters that he calls character sliders. For him, there are three sliders, or components of character:

- Sympathetic/Relatable/Nice

- Active

- Competent

These sliders are like sound mixing: the three combine to create characters. One slider may be set low and then move higher; another slider component may stay at a certain level; one of the sliders may start high and then lower over the course of the novel. If one of the sliders is really low—for example, a character is very passive—then the character should probably be higher at one or both of the other sliders. Typically, the sliders do move up and down throughout the course of the novel.

In Mansfield Park, not only do we sympathize with Fanny because of her situation, but because she has competence in a particular area: her sense of morality and her innate goodness. Because she is sympathetic and competent in a particular area, we like her as a character even though she not often active.

A few other points to consider when working with passive characters:

- If your main character is passive, other characters and events must create forward movement in the story. For example, in Mansfield Park, forward movement is created by the visit to Mr. Rushworth’s estate, the decision to stage a theatrical, and the engagement of Maria Bertram.

- Everyone has moments when they are passive. Consider how you can use this to help your character on their internal and external journeys.

- If the main character is externally passive, their thoughts and interior emotions can be revealing and insightful. For example, as her cousins their friends began to plan the theatrical, Fanny’s internal thoughts engage the reader and provide additional insight.

Fanny looked on and listened, not unamused to observe the selfishness which, more or less disguised, seemed to govern them all, and wondering how it would end. For her own gratification she could have wished that something might be acted, for she had never seen even half a play, but every thing of higher consequence was against it.

- Finally, a passive character can be a thematic choice or provide social commentary. Fanny is a woman who has almost no choices, and whose situation makes it impossible for her to be truly active. Yet through it all, she does find inner strength, and she does ultimately assert herself, sometimes with dire consequences. Many readers who love Mansfield Park see part of themselves in Fanny; they admire her quiet strength, and find her slow resistance both inspiring and empowering, for there truly are many life circumstances where we have no control, no power.

Exercise 1: Draft a short scene using one of your characters you’ve already developed, or an entirely new character. Have the character change how passive or active they are throughout the scene. They could:

- Start the scene active and become more passive

- Start passive and then become more active

- Start passive and then become even more passive

- Move back and forth several times between passive and active

Exercise 2: Choose a character from a book or a film that you typically think of as an active character. Find at least three examples in their story where they are more passive than normal or become a completely passive character. What is the impact of these moments on the story?

Exercise 3: If you are outlining, plan a point in the story where you want your character to be passive. If your character is generally active, one common place to make your character more passive is at the moment before the climax, where it seems like all is lost (this is also called “the night of despair”).

If you are revising a story, find a point where your character is passive (or more passive than in the rest of the story). How can you increase sympathy for the character at this point? Is there still a sense of forward movement in the story? What do we learn from the character’s thoughts and emotions? Is the character’s passivity a conscious choice or forced upon her? How could this passive scene be used to strengthen the theme of the story? Revise the scene to strengthen the impact of using a passive character.