Another related method to reveal character thoughts is free indirect speech. Free indirect speech (also known as free indirect discourse) was not invented by Jane Austen, but she was one of the first writers to use it in large amounts. So what is free indirect speech?

Free indirect speech is when the narrative shifts from a slightly more distant perspective of the narrator, to directly and fully into the character’s perspective, thoughts, and visceral experience.

Examples of Conveying Emotion by Revealing Character Thoughts and Free Indirect Speech

A passage from Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park will illustrate both types of emotional clues more fully.

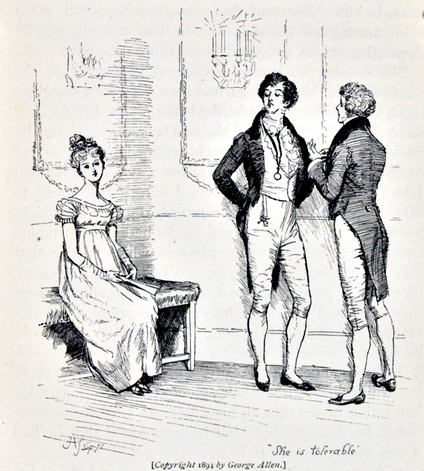

This is a scene from the second half of the book. Fanny’s female cousins have left home, and her uncle, Sir Thomas, is truly noticing Fanny for the first time. Sir Thomas decides to throw a ball. He informs Fanny that she is going to open the ball—a position of great honor.

Throughout this passage, the third person narrator sticks close to Fanny’s perspective. This provides an opportunity to describe Fanny’s thoughts and reflections, her reactions and her emotions. At just a few points, the narration slips into free indirect speech, and we are completely immersed in Fanny’s perspective. The sentences which use free indirect speech are bolded. (Note that in the original, there is no bolding—there is nothing that distinguishes or separates the free indirect speech visually from the narrator’s descriptions and summaries of Fanny’s thoughts.)

In a few minutes Sir Thomas came to her, and asked if she were engaged; and the “Yes, sir; to Mr. Crawford,” was exactly what he had intended to hear. Mr. Crawford was not far off; Sir Thomas brought him to her, saying something which discovered to Fanny, that she was to lead the way and open the ball; an idea that had never occurred to her before. Whenever she had thought of the minutiae of the evening, it had been as a matter of course that Edmund would begin with Miss Crawford; and the impression was so strong, that though her uncle spoke the contrary, she could not help an exclamation of surprise, a hint of her unfitness, an entreaty even to be excused. To be urging her opinion against Sir Thomas’s was a proof of the extremity of the case; but such was her horror at the first suggestion, that she could actually look him in the face and say that she hoped it might be settled otherwise; in vain, however: Sir Thomas smiled, tried to encourage her, and then looked too serious, and said too decidedly, “It must be so, my dear,” for her to hazard another word; and she found herself the next moment conducted by Mr. Crawford to the top of the room, and standing there to be joined by the rest of the dancers, couple after couple, as they were formed.

She could hardly believe it. To be placed above so many elegant young women! The distinction was too great. It was treating her like her cousins! And her thoughts flew to those absent cousins with most unfeigned and truly tender regret, that they were not at home to take their own place in the room, and have their share of a pleasure which would have been so very delightful to them. So often as she had heard them wish for a ball at home as the greatest of all felicities! And to have them away when it was given—and for her to be opening the ball—and with Mr. Crawford too! She hoped they would not envy her that distinction now; but when she looked back to the state of things in the autumn, to what they had all been to each other when once dancing in that house before, the present arrangement was almost more than she could understand herself.

There is so much incredible emotion conveyed in these two paragraphs. We feel as if we are with Fanny, next to the dance floor. We are with her in thought, in perspective, in the moment.

Let’s look at the difference between when the narrator conveys Fanny’s thoughts through summary, statement, and analysis, and when the narrator conveys Fanny’s thoughts through free indirect speech.

She could hardly believe it.

Her thoughts flew to hose absent cousins with most unfeigned and truly tender regret

She hoped they would not envy her that distinction now

But when she looked back to the state of things in autumn…the present arrangement was almost more than she could understand herself.

In each of these phrases, we have access to Fanny’s thoughts, but it is through the filter of the narrator. These thoughts are summarized, they’re condensed, they are stated, they are made beautiful through connection and analysis. And these thoughts certainly give the reader a lens clearly into Fanny’s emotions, in a way that’s only possible because she is the viewpoint character.

In the sentences that use free indirect speech, this narrator’s filter—even though it is a close third person filter—is removed. We are completely in her thoughts, in the moment, with no summary or larger picture perspective:

To be placed above so many elegant young women! The distinction was too great. It was treating her like her cousins!

These are Fanny’s actual thoughts, in the moment—this is her emphasis, her internal exclamations. And then, a few lines later we read:

So often as she had heard them wish for a ball at home as the greatest of all felicities! And to have them away when it was given—and for her to be opening the ball—and with Mr. Crawford too!

The power of free indirect speech is that in these moments of immersion we, as the reader, become one with the character and her perspective. Nothing separates us—for a moment, we become her.

In this last sentence of free indirect speech, note how the syntax changes. We have three clauses, all starting with “and,” stacked on each other using em dashes. For this sentence, it creates a sort of miniature use of stream of consciousness—the natural, continuous, not always sequential direction of thoughts. (Authors who are famous for their use of stream of consciousness, like Virginia Woolf, use it for much longer passages. In this passage by Austen, this sentence leans towards stream of consciousness, but because of its length is properly categorized and free indirect speech.)

The Power of Conveying Emotion Through Character Thoughts and Free Indirect Speech

One of the powers of novels and short stories is that you can convey the viewpoint character’s thoughts, perspectives, and emotions, through summary, statement, making connections to other things, and free indirect speech. This is an opportunity that is not present in the same way in other mediums (for example, the only way movies and TV can do this is through voice over narration, and this only is effective for certain stories).

While free indirect speech has the advantage of immersing us fully into the character’s thoughts and perspectives, other sorts of revelations of character thoughts (like summary, statement, and making connections) have their own advantages: they can provide context, weave in themes and insights, create layering, and sometimes create an important distance between the reader and the emotion.

Like any tools to convey emotion, these should not be used exclusively, but when coupled with other tools, these techniques can help the reader feel a connection to the characters and understand their state of mind throughout the story.

A Few Final Notes: Italics and First Person Narrators

- Instead of using free indirect speech, some modern stories will italicize character’s direct thoughts. This draws attention to it as a thought, separate from the main narrative, but has many of the same effects as using free indirect speech.

- Texts written in first person rather than third person are, by definition, entirely in the thoughts and viewpoint of the first person narrator. However, there is still often a sense of the narrator as the storyteller—the narrator is still a filter. This is especially the case with a first person past tense point of view: there is often the sense that the story is being told later, and sometimes with accompanying reflection. At times, the descriptions and thoughts will feel even closer, more immediate, and more immersive, and this can create a similar effect as using free indirect speech.

- First person present tense is meant to feel even more immediate than first person past tense, as everything is unfolding before the character (and the reader) in the present. Yet like with first person past tense, at times we can feel even closer and more submersed in the character’s perspective.