#29: Use Antagonists as Character Foils

There’s a rather brilliant musical adaptation of Emma that I saw performed live in Chicago (in February 2020, right before everything shut down!).

In one of the songs, “The Recital,” Emma plays the pianoforte and sings at a gathering (while also feeling a little jealous of the attention that Mr. Knightley is paying to Jane Fairfax). And then, Jane moves to the pianoforte and begins to play at about the 1 minute 15 second mark—her playing and singing are clearly superior to Emma’s.

“She plays well, does she not?” says Mr. Knightley.

“Only if you enjoy that polished, extremely gifted sort of talent,” replies Emma.

(You can listen to the song on YouTube—stop at about 2 minutes 39 seconds in, because then it transitions to Harriet’s musings.)

What I love about Paul Gordon’s song is that it brilliantly establishes a contrast between Emma and Jane Fairfax, which is made very directly by having them play the very same song. (To me, this works really well for the musical genre.) It’s a shorthand to establish Jane Fairfax as Emma’s foil.

What is a Character Foil?

A character foil is a character who is set up in direct contrast to another character; their opposing attributes or circumstances are featured, with the purpose of revealing things about character and story.

Having a number of different characteristics is not enough for characters to be foils: all characters should be distinctive in some way, and dozens of characters in the story will have contrasting attributes.

In order to be true foils the characters must have something substantial in common, which both invites comparison between the characters and makes their differences more apparent.

Emma and Jane Fairfax are foils to each other. Not only is Jane Fairfax “exactly Emma’s age,” but they are two of the only gentlemen’s daughters in Highbury, and they both have many accomplishments. Yet Jane Fairfax is actually more accomplished; she applies herself with dedication to things while Emma does not. And Emma is in a position of power, wealth, and security, while Jane has none of these things.

A Foil as Antagonist

Not all character foils are antagonists, but many times they are: two people with conflicting characteristics or approaches to life can make natural antagonists. Tension and conflict easily arise between these characters, and it can be a powerful storytelling technique which raises the stakes, highlights the different sorts of choices that could be made (along with resulting consequences), and sheds light on character motivations.

Whether or not a character foil also serves as an antagonist, important contrasts are demonstrated.

A character foil can serve to demonstrate contrast:

- To the protagonist

- To other characters in the novel

- To the reader

In many novels, the foil demonstrates contrast to one or two of these groups, but in Jane Austen’s Emma, contrasts are demonstrated for all three groups.

Contrast demonstrated to the protagonist:

In the opening line of Emma, we learn that Emma is “handsome, clever, and rich,” and throughout her life she has “very little to distress or vex her.”

Yet the existence and presence of Jane Fairfax does vex Emma. When Jane returns to Highbury to stay with her relatives, this is Emma’s internal reaction:

Emma was sorry;—to have to pay civilities to a person she did not like through three long months!—to be always doing more than she wished, and less than she ought! Why she did not like Jane Fairfax might be a difficult question to answer; Mr. Knightley had once told her it was because she saw in her the really accomplished young woman, which she wanted to be thought herself; and though the accusation had been eagerly refuted at the time, there were moments of self-examination in which her conscience could not quite acquit her. But “she could never get acquainted with her: she did not know how it was, but there was such coldness and reserve—such apparent indifference whether she pleased or not—and then, her aunt was such an eternal talker!—and she was made such a fuss with by every body!—and it had been always imagined that they were to be so intimate—because their ages were the same, every body had supposed they must be so fond of each other.” These were her reasons—she had no better.

Emma knows they are the same age, she knows they should have been friends—she is aware of their similarities, and she constantly attempts to emphasize their differences:

She was, besides, which was the worst of all, so cold, so cautious! There was no getting at her real opinion. Wrapt up in a cloak of politeness, she seemed determined to hazard nothing. She was disgustingly, was suspiciously reserved.

Throughout the story, Jane Fairfax also reveals things to Emma about herself: Emma finds herself worried, and perhaps even jealous, when there seems to be a romantic interest between Mr. Knightley and Jane Fairfax.

Contrast demonstrated to other characters in the novel:

The first time in the novel that Jane Fairfax is referenced is actually by Harriet Smith, in conversation with Emma:

“Do you know Miss Bates’s niece? That is, I know you must have seen her a hundred times—but are you acquainted?”

“Oh! yes; we are always forced to be acquainted whenever she comes to Highbury. By the bye, that is almost enough to put one out of conceit with a niece. Heaven forbid! at least, that I should ever bore people half so much about all the Knightleys together, as she does about Jane Fairfax. One is sick of the very name of Jane Fairfax. Every letter from her is read forty times over; her compliments to all friends go round and round again; and if she does but send her aunt the pattern of a stomacher, or knit a pair of garters for her grandmother, one hears of nothing else for a month. I wish Jane Fairfax very well; but she tires me to death.”

Emma’s verbal treatment of Jane Fairfax should act as a warning to Harriet: Emma is not perfect, her vision can be skewed, her intentions not always kind or correct. But despite seeing Jane Fairfax and Emma placed side by side, Harriet does not notice or heed this warning, and it allows Emma to inflict a fair amount of emotional damage on Harriet.

Other characters see a contrast between Emma and Jane Fairfax and chose sides. It is clear, for instance, that Mrs. Elton does not particularly like Emma. She does take a liking to Jane Fairfax and attempts to take her under her wing. Yet Mrs. Elton’s attentions are not always good for Jane Fairfax, something which Emma feels (and even begins to disagree with) as she watches Mrs. Elton attempt to take away Jane’s limited autonomy.

Contrast demonstrated to the reader:

Even before Jane Fairfax is introduced, it is clear that Emma is not always the best person—she can be unlikeable, interfering, and a bit of an antihero. Setting up a foil for Emma further highlights her failings, negative qualities, and weaknesses.

The foil also helps create a beautiful redemption arc for Emma, because it takes a long time, but Emma does begin to change and improve. Despite their differences and her long-proclaimed dislike of Jane Fairfax, Emma realizes and resolves:

“I ought to have been more her friend.—She will never like me now. I have neglected her too long. But I will shew her greater attention than I have done.”

It is not long before Emma is put to the test. She almost uses her wit against Jane Fairfax, as she is wont to do:

She could have made an inquiry or two, as to the expedition and the expense of the Irish mails;—it was at her tongue’s end—but she abstained. She was quite determined not to utter a word that should hurt Jane Fairfax’s feelings; and they followed the other ladies out of the room, arm in arm, with an appearance of good-will highly becoming to the beauty and grace of each.

Later, Jane is feeling unwell and decides to leave a social event at Donwell Abbey early. At first, Emma tries to do what she thinks would be the most kind and solicitous action—to call a carriage. But ultimately, she allows Jane Fairfax to do what Jane wants, which gives her the autonomy and societal power she is often denied. The following passage begins with Jane speaking:

“I am fatigued; but it is not the sort of fatigue—quick walking will refresh me.—Miss Woodhouse, we all know at times what it is to be wearied in spirits. Mine, I confess, are exhausted. The greatest kindness you can shew me, will be to let me have my own way, and only say that I am gone when it is necessary.”

Emma had not another word to oppose. She saw it all; and entering into her feelings, promoted her quitting the house immediately, and watched her safely off with the zeal of a friend. Her parting look was grateful—and her parting words, “Oh! Miss Woodhouse, the comfort of being sometimes alone!”—seemed to burst from an overcharged heart, and to describe somewhat of the continual endurance to be practised by her, even towards some of those who loved her best.

The contrast between the characters and their evolving relationship creates a powerful story for readers. While Emma and Jane Fairfax never have a complete, total reconciliation, the transformation of their relationship is dramatic.

Wrapping up

Not all character foils need to have this sort of reconciliation. And sometimes, a character foil is used for a character other than the main protagonist. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy and Mr. Wickham acts as foils to each other, and while a sort of agreement is reached between them at the end of the novel, it is more of a triumph of Darcy and his principles over Wickham.

Using character foils can be a powerful tool, especially with antagonists, which can create marked contrasts for the protagonist, for other characters, and for the reader.

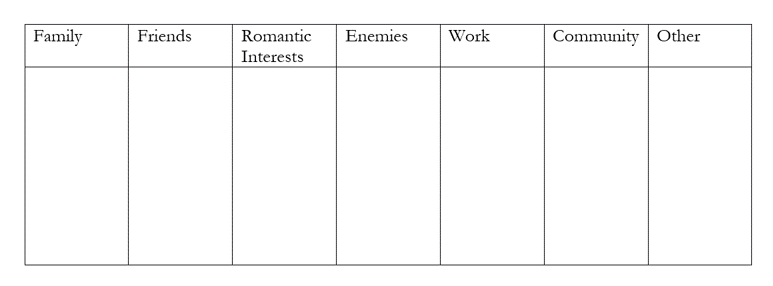

Exercise 1: Think about one of your favorite character foils from a book or a movie. What do the characters have in common? What is different about these characters? Who notices this contrast, how does this foil effect the plot, and what is the impact of this foil on the reader?

Exercise 2: Take one of your characters who does not have a foil (either from a story you have already written or a character you have brainstormed). Craft a character who could be an effective foil for this character. What would be the advantages of using a foil in your story? What would be the disadvantages?

Exercise 3: Choose a classic fairy tale character, like Belle from Beauty and the Beast. Now create a character foil for this character. The catch: you have to use this random number generator.

Use the random number generator 3 times to choose 3 of the following possible contrasts. Use these three types of contrasts to craft a character foil for the fairy tale character (but also make sure to give the characters enough in common that they are set up as foils).

General categories of possible contrasts:

- Background

- Education

- Personality

- Choices

- Approach to life

- Physical attributes or abilities

- Mental attributes or abilities

- Economic status

- Power/hierarchy

- Gender

- Passive/active

- Strengths/weaknesses

- Wants/needs

- Sympathetic/unsympathetic

Bonus: do the same exercise, but this time use the generated numbers to choose the things that are similar about the characters.