Original photo by Dimitris Papazimouris, Creative Commons license

Original photo by Dimitris Papazimouris, Creative Commons license

Key 1: Dialogue is an Expression of Character

Dialogue is the impression of how people speak in real life, but actually much more interesting, with more forward motion. Dialogue is one of the core elements of storytelling, and it needs to be used well.

Image Credit: Beppie K, Creative Commons license

Dialogue is an expression of character, background, education, locality, and circumstance. Listen to how people talk and you’ll see that who they are and the situation they find themselves in will influence what they say and how they say it.

Key 2: Prune Real Conversations to Create Realistic Dialogue

Most writing manuals agree that while you should listen to people and imitate speech patterns, you shouldn’t use verbatim conversation. Writer Aaron Elkins gives an example of an actual conversation he recorded:

“You know how, how…but..some mornings the minute you walk in the door—”

“Every morning.”

“Yes, that’s how these, the way they, the way they…”

“No, it’s not. It’s not the, the—“

“Yes, it is, it is. Because if you, unless you—“

“No, uh-uh, absolutely not.”

While accurate to real life, that would be terrible dialogue for fiction.

If you’re not supposed to use actual conversation, how do you write realistic dialogue?

Aaron Elkins explains: “Realistic dialogue attempts to capture the flavor of real speech, but it does it selectively. Word repetitions, hesitations, stammers, and dead ends have to be ruthlessly pruned. So do many of the polite conventions.” (page 136 — see end of post for sources and further reading)

William Noble makes the same point, giving an example of how people actually speak, and what good dialogue looks like. (see page 259)

How people actually speak:

“Where do you live?”

“230 State Street.”

Good dialogue:

“You live around here?”

“If you want to call it living.”

Key 3: Use Dialogue Attribution (also known as Tags)

One of the key decisions you have to make when writing dialogue is how to attribute it to your characters. A “tag” is the noun (or pronoun) and verb you use next to a quotation. When it comes to writing, there’s actually a lot of debate on how you use tags. Having read the arguments, to me it seems that it comes down to the style you want to write in and the impact that style will have on the reader.

Aaron Elkins explains that there are “three camps” for approaches to dialogue.

Photo Credit: Al_HikesAZ, Creative Commons license

Camp 1: He said/she said. Don’t use any adverbs or fancy verbs.

“Wonder where his mummy is?” said Harry, frowning.

“Given her the slip by the looks of it,” said Ron.

“Why, though?” said Hermoine.

—Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, J.K. Rowling

Camp 2: Vivid verbs. Be expressive!

Sample verbs: Snorted, sighed, chuckled, gasped, exclaimed, rasped, hissed, etc.

I couldn’t actually find a book on my bookshelf that used just vivid verbs. Apparently they’re out there, and I’m just reading the wrong genres.

Camp 3: Some variety, but try not to draw too much attention to it.

Elkins says this is his approach, and that he tries not to use an unusual verb like “whispered” more than once per chapter.

“Barnabus Wren,” I said impatiently, “why do you shake so? Have you seen a ghost?”

“No,” he confessed, “but all the talk is that you have, Keturah.”

—Keturah and Lord Death, Martine Leavitt

Key 4: Omit Attributions When You Can

If it’s a dialogue between two people and it’s clear who is speaking, you can get away with giving attributions every five or six lines.

Screenshot from Pride & Prejudice (2005)

“It is your turn to say something now, Mr. Darcy. I talked about the dance, and you ought to make some sort of remark on the size of the room, or the number of couples.”

He smiled, and assured her that whatever she wished him to say should be said.

“Very well. That reply will do for the present. Perhaps by and by I may observe that private balls are much pleasanter than public ones. But now we may be silent.”

“Do you talk by rule, then, while you are dancing?”

“Sometimes. One must speak a little, you know. It would look odd to be entirely silent for half an hour together; and yet for the advantage of some, conversation ought to be so arranged, as that they may have the trouble of saying as little as possible.”

“Are you consulting your own feelings in the present case, or do you imagine that you are gratifying mine?”

“Both,” replied Elizabeth archly; “for I have always seen a great similarity in the turn of our minds. We are each of an unsocial, taciturn disposition, unwilling to speak, unless we expect to say something that will amaze the whole room, and be handed down to posterity with all the eclat of a proverb.”

“This is no very striking resemblance of your own character, I am sure,” said he. “How near it may be to mine, I cannot pretend to say. You think it a faithful portrait undoubtedly.”

“I must not decide on my own performance.”

—Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

Key 5: Mix in Action or Thought

Image Credit: Vyacheslav Bondaruk, Creative Commons License

One of the most powerful dialogue tools is to include actions and characters thoughts, mixed in with the dialogue. This can actually be used as a replacement for dialogue attribution. Or it can be used to add a “beat”: when a person is speaking, sometimes you need a pause between parts of what she is saying in order to add emphasis or show a passage of time, and an action beat can be a perfect way to do that.

“Let’s go to the bow.” I tugged on Elle’s sleeve.

She made a face. “I said I’d meet the others from lunch by the pool.”

I hesitated, darting my eyes between her and the receding deck.

“You go.” Elle gave me a gentle push. “Just be sure to meet us for dinner at seven, okay?”

—A Change of Plans, Donna K. Weaver

This example uses a mixture of tags and action:

“Does that server look familiar?” Marasi asked, turning and watching him go.

“He must have served us last time we were here,” Lord Harms said.

“But I wasn’t with you last—”

“Lord Harms,” Waxillium jumped in, “has anything been heard of your relative? The one who was kidnapped by the Vanishers?”

“No,” he said, taking a sip of his wine. “Ruin those thieves. This kind of thing is absolutely unacceptable. They should confine such behavior to the Roughs!”

—The Alloy of Law, Brandon Sanderson

Key 6: Limit Your Use of Adverbs in Dialogue Tags

Most writing experts agree that you should use adverbs in dialogue tags as rarely as possible, because it distracts from what the speaker is saying and it can often be more useful to provide an actual action the speaker performs (“Ryan flinched”) than give a modifier about how they’re saying something (“Ryan said flinchingly”). (see Chiarella, pages 141-2)

Of course, every single book I looked at for examples used adverbs in the attributions, but seemed to do so very selectively. Here’s an example of good adverb usage:

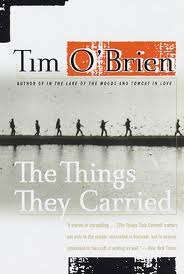

Again there was some silence as Mitchell Sanders looked out on the river. The dark was coming on hard now, and off to the west I could see the mountains rising in silhouette, all the mysteries and unknowns.

“This next part,” Sanders said quietly, “you won’t believe.”

—The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien

The key is asking yourself, can someone actually verbally say something in this manner and is this the very best way to say it? If the answer is yes, use an adverb. If the answer is no, change it to an action or a description. For example, “he said quietly” is physically possible to do, and it’s a useful adverb. But as Tom Ciarella points out, “she said quaintly” is not truly possible to do—she might be a quaint person or dressed in a quaint way or be looking at a quaint portrait while saying something, but there’s no real way to say something quaintly.

Key 7: Interject Silence or a Change of Subject

Sometimes instead of coming up with a direct verbal reaction from your character it’s better to use silence, or have your character change the subject. Tristi Pinkston writes that “Sometimes the absence of dialogue says more than dialogue itself.”

Image Credit: Francesco, Creative Commons License

Pinkston gives a nice example of revealing things about a character through what she chooses not to say and deflecting a question:

“What happened to Greg?” I asked.

Viv stepped over to the window and pulled back the curtain, staring down to the street below. I wondered if I should break the silence, but she finally said, “Let’s go out to dinner. I want a good steak and some mashed potatoes.”

–Tristi Pinkston

Note: I write more about pauses in dialogue in my post 10 Keys to Writing Story Beats in Novels.

Key 8: Test your Dialogue

As a cardinal rule, you should always read your dialogue aloud. It might look good on paper, but before you speak it, you’ll have no idea what it actually sounds like.

Image Credit: Paul Graham Raven, Creative Commons License

It’s also a good idea to look at the dialogue of an individual character across the entire novel, to make sure it’s consistent. It takes time, but it’s worth it.

Key 9: Look for Inspiration from your Favorite Authors

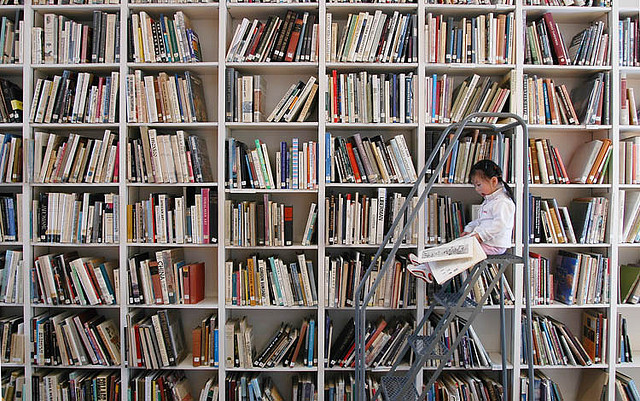

The Romans used imitation as a way for students to learn oration. It’s a great way to learn writing techniques as well. Open a book on your shelf to a random page, and analyze how the author uses dialogue. It may also be useful to analyze dialog in the genre you’re writing in.

Image Credit: QQ Li, Creative Commons license

Key 10: Consider what Each Line of Dialogue Adds to the Story

William Noble gives five things he thinks good dialogue should do:

- “characterize the speaker;

- establish the setting;

- build conflict;

- foreshadow;

- explain” (page 261)

Each line you include should have a very clear purpose. But you can’t just force dialogue on your characters to meet your own ends as an author–it has to be dialogue that works for your characters and their desires. One of the most useful pieces of advice for writing dialogue comes from Kurt Vonnegut: “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” When your characters are talking, as a writer you should be very clear on what each character wants, even if they’re not openly sharing that with each other.

Whether it’s adding to characterization, to plot, or to foreshadowing, every line of dialogue should forward the story. Make it count!

Image Credit: Daniel Pozo, Creative Commons License

Dialogue Writing Exercises

Image Credit: Oliver Hammond, Creative Commons license

Exercise 1:

- Choose 2 characters. Have one of them start a dialogue with a line that implies some conflict, such as “I told you to buy cheese…” (You can even do the exercise with that exact line.) Now do a rush write. As fast as you can, write 6 to 10 lines of dialogue between the two characters. The catch? You can only write dialogue – no attributions, actions, etc.—just the words they are saying.

- Consider what it is each character wants, their background, their distinguishing characteristics, and how these things will impact what they say and how they say it. Revise your dialogue (still just the words they are saying) to better reflect your characters.

- Add tags or dialogue attributions. He said/she said, or fancier verbs if you choose. But don’t overdo it. Instead of tags you can add an action or thought. Or you can create a beat in the midst of a statement by adding an action.

- Look at the dialogue you’ve written, and make sure every word counts, that everything the characters say, and everything else that you’ve added in, really contribute. Cut anything that doesn’t.

- Compare your original dialogue with your final version.

Exercise 2:

- Write a sort dialogue between three characters. It can be about anything you want and should be at least 6 lines long. The only verb you can use is “said.”

- Rewrite the dialogue using only vivid verbs.

- Rewrite the dialogue using no normal attribution tags. Instead, let us know who is talking by including actions and descriptions of characters.

- Now rewrite your dialogue using whatever combination of tags and action you think will make it work best.

Sources and Additional Resources on Writing Dialogue

Check out my new novel!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider learning about my new spy novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, coming in April 2021 from Tule Publishing.

Read More

(The above post includes more on dialogue, including the Three Beat Rule of Dialogue.)