Writing Powerful Emotion Beats in Fiction

An emotion beat is what makes the novel or short story distinctive—we can be inside a character, experiencing the emotion with her, and that makes the reading experience powerful. For it to work, the right emotion beats must be used in the right spots.

In Part 1 of my series 10 Keys to Writing Story Beats in Novels, I discussed the story beat, the beat sheet, and the pause or inaction beat. In Part 2 I discussed the action beat, the dialogue beat, and beat variation. In this post, with keys 7 through 10, I will discuss the emotion beat in depth.

Key 7: Use Emotion Beats to Connect Readers to the Characters

I heard someone say that we can’t really understand any of the people around us, and that is why we love reading. Only through reading can we can truly grasp the emotions, desires and perspective of someone other than ourselves. The emotion beat is what creates this connection between reader and character.

Image by Kevin Conor Keller, Creative Commons License

There are four basic types of emotional beats:

1. Internal Physical Sensations

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene felt sick to her stomach. It was their last chance—they had needed that job desperately.

2. External Physical Sensations

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Suddenly, the warm air blowing from the heater felt too hot, stifling even. Irene opened the window, letting in the cold of winter.

3. Physical Actions (including hand gestures, facial expressions, and larger physical movements)

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene pressed her lips firmly together, trying not to say something she would regret later.

4. State the Emotion

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene was frustrated. He could’ve at least visited the company’s website before going into an interview. But as always, he insisted on doing it blind.

A great resource for physical sensations and actions that show emotions is the book The Emotion Thesaurus. You’ll notice that there is overlap between emotion beats and action beats; I’d categorize something as an emotional beat if conveying emotion is the most important function. Stating the character’s emotion should always be the last resort, though it can be used effectively.

Key 8: Use Emotion Beats that are Distinctive to your Story World or Character

The four basic types of emotional beats start to feel repetitive if that’s all you use in your story. Another type of emotional beat that’s extremely effective is using actions or thought patterns that are distinctive to your character or story world. A wizard in Harry Potter might reach for a wand or use magic in certain emotional states. A motorcycle rider may convey his emotions through how he rides his bike.

Photo circa 1980s, via Seattle Municipal Archives, Creative Commons license

All sorts of things can become an emotional beat that is carried throughout your story: habits or tics or possessions. How you vary them will then create a powerful emotional reaction for you reader.

The superhero novel Dangerous by Shannon Hale is full of examples of emotional beats that are distinctive to the characters and the story world. The main character, Maisie, is half-Latina, and her cultural heritage impacts her emotional beats. Here Maisie is listening to her mother on the phone, and emotionally reacting to her words:

The superhero novel Dangerous by Shannon Hale is full of examples of emotional beats that are distinctive to the characters and the story world. The main character, Maisie, is half-Latina, and her cultural heritage impacts her emotional beats. Here Maisie is listening to her mother on the phone, and emotionally reacting to her words:

“Maisie, you haven’t been…contenta lately.” She used the Spanish word for content or happy, as if it were too stark, too uncomfortable to say it in English. I hadn’t realized that she’d noticed. “Are you now? How do you feel?”

This emotional beat is distinctive to Maisie, her relationship with her mother, and her cultural heritage.

One of the other characters in Dangerous, GT, often chews gum. The way he unwraps it or the way he chews it is a point of emotional control for GT, and so the description of his gum (or other taste metaphors) it is often used as an emotional beat in connection with his character.

At one point in the novel, GT is holding another Maisie’s father hostage. He has set demands for Maisie, and a time for when her father will be killed if she doesn’t agree. Maisie asks how she can know if GT will keep his word.

“You don’t know,” GT said, snapping on his gum as if we were chitchatting about the weather. “But you have no other choice. Two minutes, ten seconds.”

If at all possible, use emotional beats that are distinctive to your character and storyworld. It will make all the difference in your storytelling.

Key 9: Use Advanced Emotional Beats to Better Convey Your Character’s Feelings

In addition to beat distinctive to your character and story world, there are a handful of other advanced emotional beats that can powerfully convey feelings:

1. Setting: Use what your character notices about the setting to convey emotion.

Example of using a setting that parallels emotion:

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene forced her eyes away from him, out the window. The last leaf that had hung onto the tree all winter long fluttered to the ground.

2. Metaphor or Simile

Example of using a setting that contrasts emotion + a simile:

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene forced her eyes away from Russ, out the window. The green on the tree was oversaturated, like a poorly-made Technicolor film, mocking her with its cheeriness.

3. Mini Flashback

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene had known this could happen, yet his words still shook her, the way the doctor’s words had shook her when IVF had failed for the third time. She knew what would happen now—the sinking despair, the gradual recovery, and all the while the knowledge that this had been the last chance.

4. Mini Flashforward

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

Irene looked at the floor. One of these days she would leave him, take her terry coat and walk right out the front door.

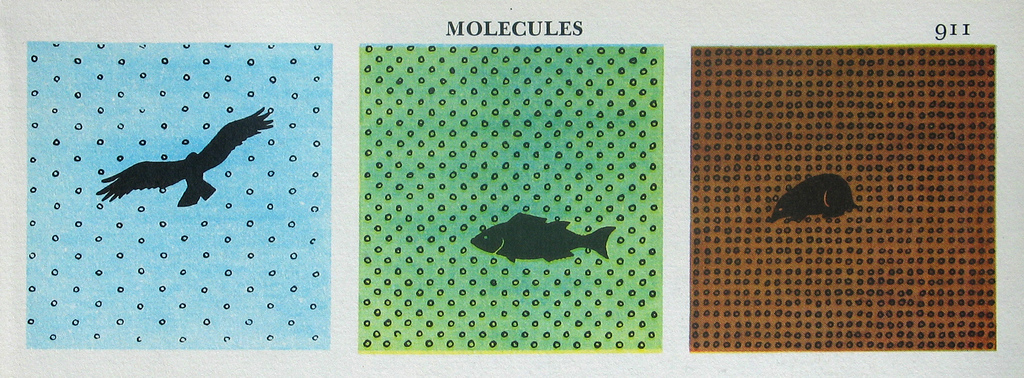

5. Surreal Images

“I didn’t get the job,” said Russ.

She had expected this, but that did not stop the rush of despair. The couch swallowed Irene whole.

Image by James Tworow, Creative Commons license

Using these techniques well will create a distinctive style and voice, in addition to conveying emotion. Of course if you overuse any one of these types it will probably backfire.

Here’s a passage from Darkness at Noon by Arthur Koestler that uses almost of almost all of these emotional beats. The main character has spent his life working for a totalitarian regime. Now he is a political prisoner for that same regime. Here is his emotional reaction when he finds out that one of the other prisoners has been tortured by steambath:

He lit his last cigarette and with a clear head began to work out the line to take when he would be brought up for cross-examination. He was filled by the same quiet and serene self-confidence as he had felt as a student before a particularly difficult examination. He called to memory every particular he knew about the subject “steambath.” He imagined the situation in detail and tried to analyse the physical sensations to be expected, in order to rid them of their uncanniness. The important thing was not to let oneself be caught unprepared. He now knew for certain that they would not succeed in doing so, any more than had the others over there; he knew he would not say anything he did not want to say. He only wished they would start soon.

His dream came to his mind: Richard and the old taxi-driver pursuing him, because they felt themselves cheated and betrayed by him.

I will pay my fare, he thought with an awkward smile.

Note: credit for coming up with these categories of emotion beats needs to go to author Janci Patterson, whose new book Everything’s Fine is an excellent example of emotion beats.

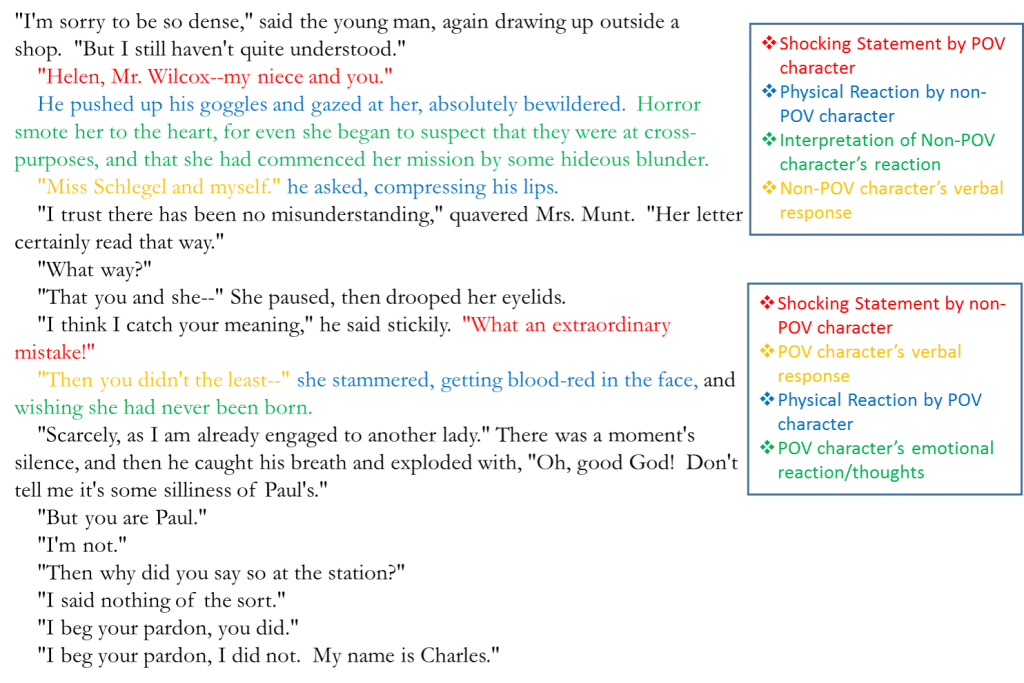

Key 10: When Something Important or Shocking Happens, Use a Complex Reaction Beat to Show the POV Character’s Interpretation of Events

Most of the time you can follow an action beat with another action beat, or a line of dialogue with another line of dialogue. Yet that’s not always enough.

If there’s an action beat or a dialogue beat that is shocking to the viewpoint character, then to take advantage of the moment we have to follow this with a fleshed out reaction beat, that includes a feeling/thought, a physical action, and speech. Otherwise something like this happens:

“I quit my job,” said Russ.

“I’m sure it will all work out,” said Irene.

We have no idea how Russ or Irene feel about the situation. This could be devastating to them. This could be an everyday thing. This could be the breaking point for Irene, yet she’s trying to put on a hopeful face. We have no idea, and because there aren’t any emotional beats, we feel disconnected from the characters. And if the dialogue or the action is truly shocking or important to the characters, a one sentence emotion beat is probably not enough.

Shocking action or dialogue must be followed by a series of beats that create the reaction—a standard way to do this is use a physical reaction beat, an emotion/thought reaction beat, and then a dialogue reaction beat.

“I quit my job,” said Russ.

Irene coughed her coffee out of her mouth, sending flecks of brown liquid across the table. She sucked in a deep breath, stood, and wiped off the table. Worry gripped her. This could not have happened at a worse time. Finally she found the courage to speak.

“I’m sure it will all work out,” said Irene, putting on a brave face.

We now understand this dialogue and what it means to the characters because a fleshed-out, complex reaction beat has been used.

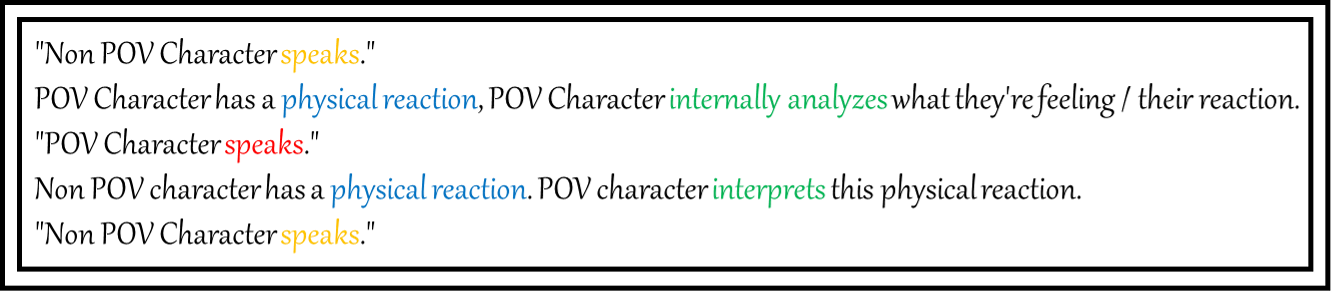

Authors Janci Patterson and Heather Clark provide this formula for complex reaction beats:

In describing what he calls “Motivation-Reaction Units” Dwight V. Swain thinks the order should be reversed, with the feeling or thought coming before the physical reaction. (Also see Heather Clark’s and Janci Patterson’s posts on the subject.) Regardless of the order, if it’s a key emotional reaction, you probably need thought/feeling, action, dialogue, and potentially another powerful emotion beat.

In the classic novel Howards End by E. M. Forster, a character named Helen becomes engaged to a man, Mr. Wilcox, that she has only known for a few days. Her Aunt Juley goes to try to break off the engagement. Unfortunately she broaches the subject with the wrong Mr. Wilcox.

Writing Exercises

Complex Reaction Beats Exercise

Here’s a passage of dialogue without any emotional reactions to accompany some rather big statements:

“I’m having a baby,” said Tessa. “You should’ve told me earlier,” said Mark. “Would it have made a difference?” asked Tessa.

Now rewrite this dialogue from Mark’s POV, with physical reactions and internal reactions.

“I’m having a baby,” said Tessa. (non-POV character)

[Write Mark’s physical reaction] [Write Mark’s internal feeling/reaction]

“You should’ve told me earlier,” said Mark. (POV character)

[Write Tessa’s physical reaction] [Write Mark’s interpretation of her reaction]

“Would it have made a difference?” Tessa asked.

If you need to, you can switch the order of the beats, sub out an emotional beat, or add additional emotional beats. My writing group did this exercise and came up with a wide variety of reactions for the characters.

Beat Mania Exercise

Take the line of dialogue “It won’t be ready in time.” (Or you can choose a sentence from one of your stories.)

Now write ten different possible emotional beats, using each type of emotion beat discussed in this post:

- Internal Physical Sensations

- External Physical Sensations

- Physical Action

- State the Emotion

- Emotion Beat Particular to Character/Story World

- Setting-related Emotion Beat

- Metaphor or Simile

- Mini-Flashback

- Mini-Flashforward

- Surreal Imagery

(This should turn out like the “I didn’t get the job” example used throughout this blog post.)

Of your results, which emotion beat do you like best and why?

Revision

Print out several pages from your novel. Highlight and label each of your beats (physical sensation, setting, flashback, stating the emotion, internal sensation, physical action, etc). Are you doing all one type? Ignoring one type altogether? Skipping places that need beats? Now that you’ve analyzed, revise!

Check out my new novel!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider learning about my new spy novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, coming in April 2021 from Tule Publishing.

Read More:

Original drumming at the beach image by Jason Turgeon, Creative Commons license

A metaphorical depiction of molecules, from The Golden Book Encyclopedia, 1959. Image Credit:

A metaphorical depiction of molecules, from The Golden Book Encyclopedia, 1959. Image Credit: