I recently signed with a literary agent, Stephany Evans of Ayesha Pande Literary, and like most agents, she had revision notes for me.

But before I talk about my process of revising for a literary agent, let’s start with a little background. A lot of people ask, “When you start submitting, is your book finished?”

The answer is, your book should be as polished as you can make it with the help of your writing group, beta readers, and critique partners.

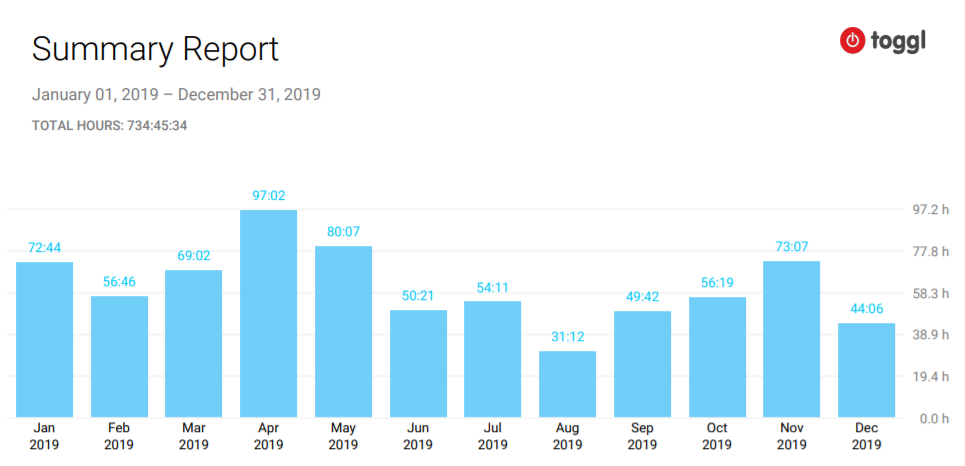

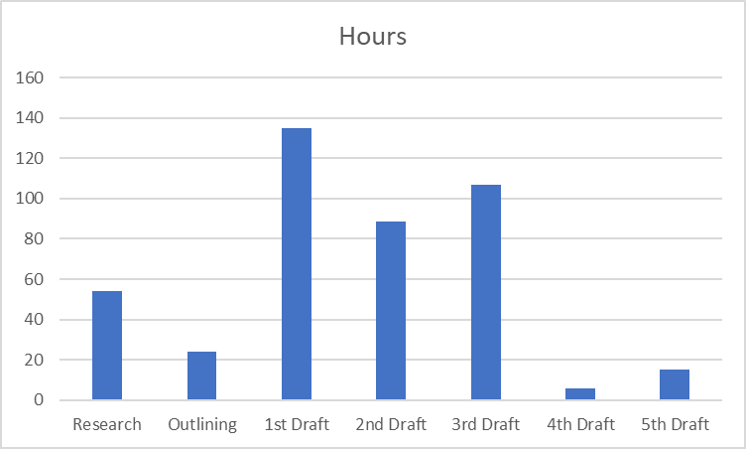

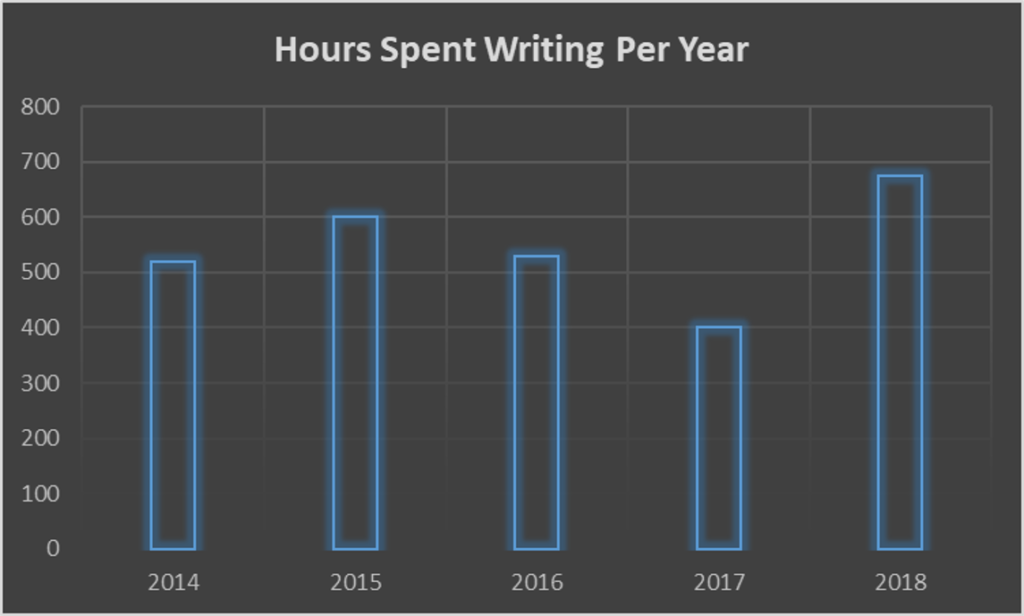

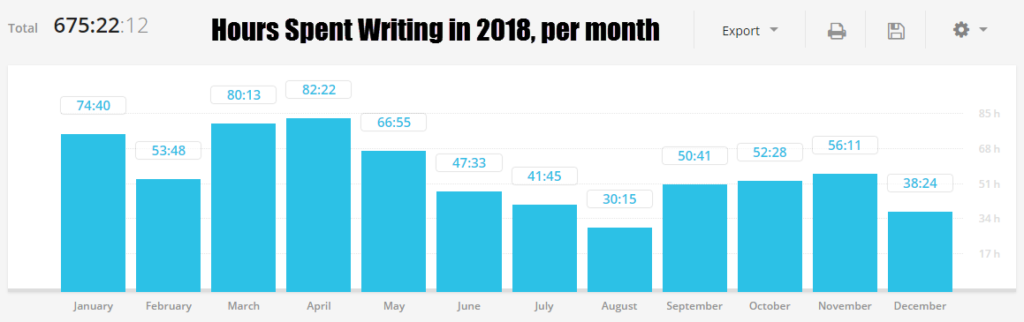

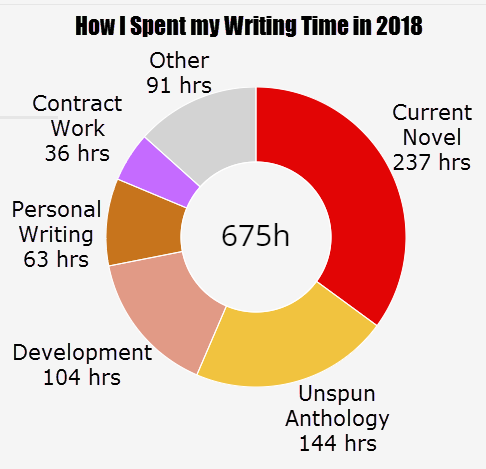

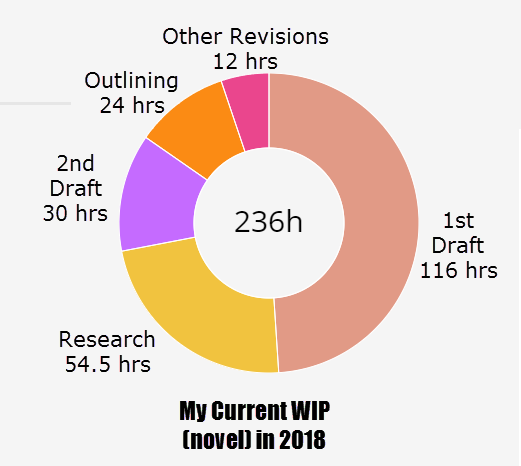

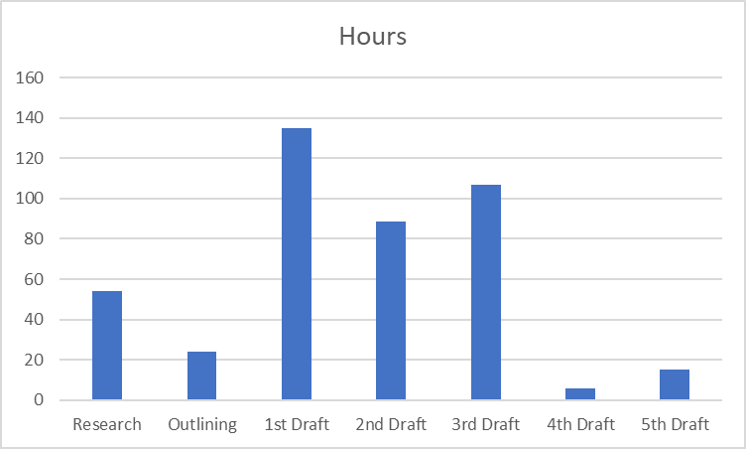

For this book, which we shall call my Regency Mystery novel, I spent 54 hours doing research, 24 hours outlining, and 135 hours on the first draft. (I actual researched, outlined, and wrote the first draft all at the same time, based on what was needed any given week—it wasn’t sequential.)

Then, I did lots of revising: 88.5 hours on the second draft, then I sent it to readers for feedback, 107 hours on the third draft, then I sent it to readers again, who did not have much feedback, and then 6 hours on the fourth draft.

At that point, I felt like my Regency Mystery novel was as ready as I could make it, so I started querying literary agents.

One of these agents requested the beginning of my book, liked it, and asked to read the whole book. I sent it to her. She read it. She rejected it.

However, it was a really helpful rejection letter. It was only one paragraph long, but it included a couple of sentences about what she saw as a structural problem in my book.

I thought about it for a few weeks (I often have to digest feedback before I can figure out how to incorporate it) and then I wrote a fifth draft. Making the structural change to increase tension took about fifteen hours.

Then I started querying again.

Query. Query. Query. Query. Query.

I queried a lot of agents at this point—I was getting requests for partial manuscripts, so I knew my query letter was working, and I was getting requests for full manuscripts, so I knew people liked my opening pages. I had several dream agents that I still hadn’t contacted, and I wanted to make sure that I queried them.

Query. Query. Query. Query. Query.

I queried 51 agents in all.

One of my dream agents, who I hadn’t queried in the first rounds because she wasn’t specifically looking for historical mystery, wrote back and asked for my manuscript. I sent it to her. A week and a half later she emailed me and said was half-way through and loving it. Not long after, she sent another email: she wanted to speak with me on the phone about my book.

And thus, one of the most anticipated moments for a writer:

The Call

(Despite how cool rotary phones look, I don’t know how to use them. I used my cell phone.)

The phone call went like this:

- General pleasantries and conversation. To my utter horror, the call kept dropping.

- We got a good connection established. We decided to skip general pleasantries.

- Stephany Evans told me all the things that she loved about the book. It was a lot of things. I really got the sense that she understood my vision—she loved my premise, my characters, my writing style, the emotion and the themes.

- We talked about revisions.

I had left a number of loose ends in my book that I didn’t realize were there (an important character disappeared and didn’t have a backstory, several characters were never fully tied into the mystery plot, could the boat serve a bigger purpose, to complete this relationship arc this character needs to apologize, etc. etc.). However, there was something much bigger: I was staying on the fringes of the mystery genre. While my novel included all sorts of mystery and sleuthing and discovery, there was no Big Mystery, no Large Problem that occurs near the beginning and then needs to be solved. A Big Mystery could be a dead body, a kidnapped person, a significant theft, etc.

As we talked about this revision, it was like stepping into a Frederick Edwin Church painting: all of a sudden there was a breathtaking vision before me of what my novel could be.

Cotopaxi by Frederic Edwin Church

One of the reasons I was excited was the feedback felt like it was making more the book into more of I wanted it to be, instead of shifting it into something else. (To me, this is a key for revisions, whether you are revising for an agent, an editor, or a critique partner.)

Back to the phone call.

- Stephany Evans asked if I would be willing to make the sort of revisions we had discussed. I said something along the lines of, “Yes! I think adding a subplot would be work really well.” She then asked me about the time frame—how long would it take me to revise? I said about a month, and then I asked if I could revise and resubmit the manuscript to her. (“Revise and resubmit” is a pretty common request in the publishing industry.)

- Stephany said that she actually wasn’t asking me to revise and resubmit—she was confident I would be able to make the revisions, and she wanted to make an offer of representation.

- I said that I was extremely interested and would love to work with her, but that other agents were looking at it. We made a plan to talk in the not so distant future and that afternoon I rapidly contacted everyone else who had the query or the manuscript.

I didn’t end up receiving other offers or representation. But, one of the other agents who read the full manuscript gave me the same big picture feedback—she pointed out the same, Big Mystery plot problem. This was a great confirmation to me that the revisions I was about to start were really on track with what the book needed.

During the time while I was waiting to hear back from the other agents, I did extensive outlining and planning for how to tackle the revision. And then, as soon as I signed a contract with Stephany Evans, I plunged into the revisions.

I spent 77 hours revising over the course of 5 weeks.

Most of the time went to adding the subplot, which required introducing several characters earlier in the book, adding a new character, and writing three and a half new chapters. A lot of the other chapters had new partial or full scenes; other scenes had to be rewritten to reflect the Big Mystery.

The first hundred pages of the book didn’t change much at all. And then, things started to get colorful.

I used track changes, and so anything I changed, added, or deleted shows up in red. When you look at the book in 10% size it really gives you a sense of what happens when you add a dead body to your book.

My book is now about 15,000 words longer than it was before (sixty pages or so, depending on font and margin size). The great thing was that I was able to solve all of the loose ends by the addition of the subplot—it fixed not only the big problem with my book, but the smaller ones as well.

Over the course of the five weeks, I didn’t just change and add things—I also got feedback from critique partners and my writing groups on every single new scene in the book. It is hard (in my opinion) to make new material match writing that has been through multiple drafts, so I knew I needed eyes on the manuscript.

I only sent the full manuscript to one person, a trusted friend who is an incredible writer (and who also happened to be one of my college roommates). She had never read a single word of the book before, which was useful because she came at the manuscript completely fresh. She knew that I had added a subplot but did not know which one. And when she emailed me after reading the book, she thought it was a different subplot that was new. She was shocked that the new subplot was actually the Big Mystery, because it seemed so essential and interwoven in the story.

And that is the story of how I got my agent, and the revisions I have done for her so far. I love what my book is becoming, and I am excited to see what happens next.