1000 Hours of Writing in 2021: A Year in Review

In 2021, I spent 1000 hours writing.

1000.

A few weeks ago I realized how close I was to 1000 hours of writing for the year, so I decided to go for it and get in the last few hours.

1,000 hours 1,000 hours

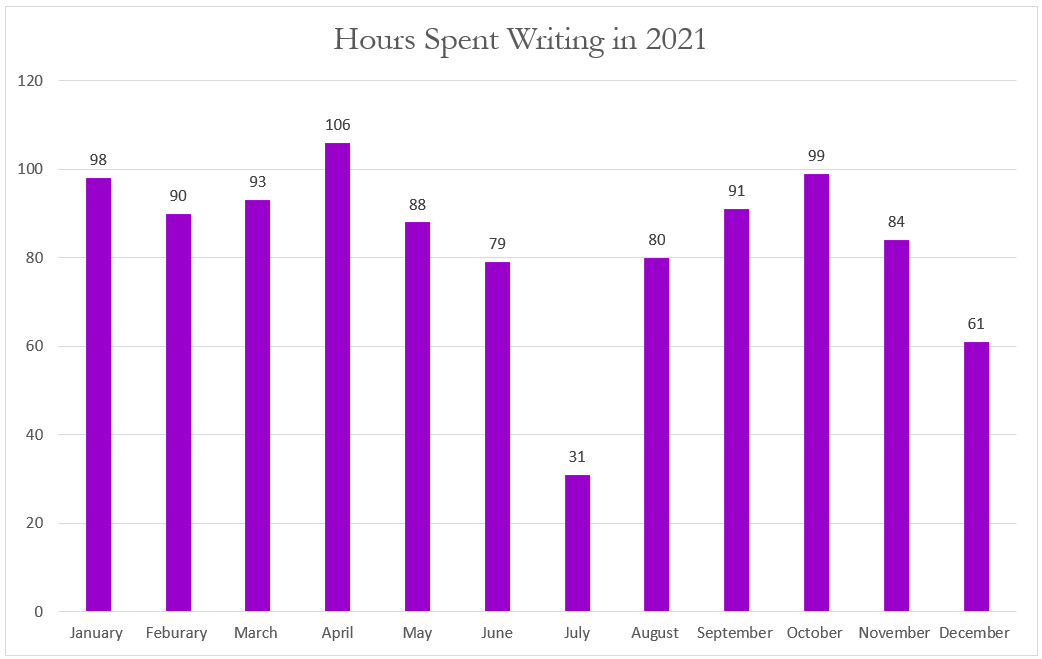

If you look back on previous years, there were a number of years when I was firmly in the 400 to 600 hours a year range (so writing on average 60 to 100 minutes a day). Last year was my most writing time ever, with 909 hours total–so an average of 150 minutes or 2.5 hours a day. 1000 hours per day is an average of 165 minutes a day, or 2.75 hours.

Of course, I was not actually writing 2.75 hours a day–some months I wrote a lot more than that, some months a lot less:

Now, a qualifier. I did not spend 1000 hours typing. I’ve talked about this in previous year-in-review posts, but I believe in being pretty expansive in my definition of writing. Daydreaming about story ideas counts as writing. Listening to writing podcasts counts as writing. Submitting stories for publication counts as writing. That said…

What specifically did I work on in 2021?

First off, my debut novel was published!

When I was five years old, I decided that I wanted to be an author and publish books. While I have had a number of shorter works published, this year was my first to publish a book.

Having my book out in the world has been thrilling and tiring and exciting and overwhelming and wonderful all at once. Most of all, I’m grateful to have a story that I wanted to tell out in the world. And I’m grateful to everyone who has read and shared and reviewed my book–I truly appreciate all of your support for my stories!

While The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet was a huge milestone for my year, it actually didn’t take up most of my writing time. (The time that it did use was sharing the word about the book on social media, blog posts, sending out my newsletter, being a guest on podcasts, updating my website, etc.–aka marketing.)

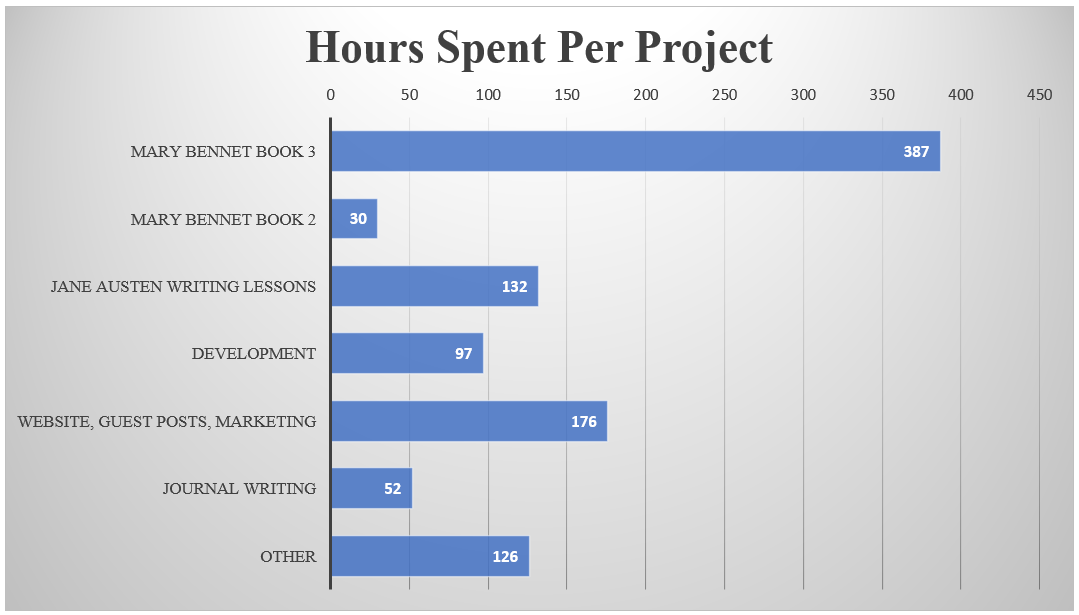

Here’s a snapshot that shows how I spent my writing time throughout the year:

Book 2 in my Mary Bennet series—The True Confessions of a London Spy–comes out in a little over two months, on March 1, 2022. However, this past year I only spent 30 hours on it, and that was for final revisions. (Most of the time for that book came in 2020, when I spent 347 hours on it, and from 2018, when I wrote a very rough first draft.)

What I did spend most of my time on in 2021 was Book 3 in the Mary Bennet series, The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception. I spent 387 hours on the book. This included brainstorming, research, outlining, reading newspapers from the time, and four drafts. The book is still not finished–I still have 3-4 revision passes on it with the publisher that will happen in early 2022.

Other things I worked on:

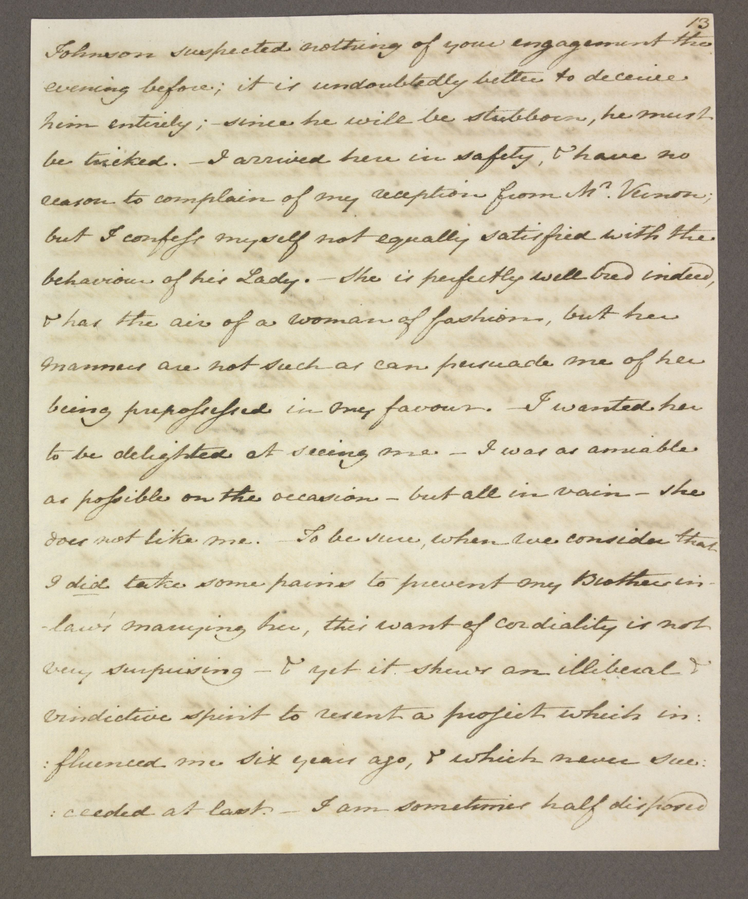

Jane Austen Writing Lessons. This has been a project of joy, as I’ve deep dived into writing through the lens of Jane Austen. Basically, this is everything I know about writing in a series of blog posts, and it was actually selected by the Write Life as one of the 100 Best Websites for Writers in 2021.

The 97 hours spent on development included my monthly writing group, critiquing the writing of others, accounting, networking, goal setting and tracking, and learning about writing through listening to writing podcasts and reading books about writing. Developing yourself as a writer is so essential at every stage of the writing or publishing process you are at, and so it’s something that I continue to prioritize.

It’s also important to do writing that’s just for yourself, and that’s where my 52 hours of journal writing came in. And then there were all sorts of other smaller writing projects and writing-related tasks that I worked on throughout the year.

How much of the thousand hours was spent actually outlining, writing new words, or revising? I have no idea, and I absolutely refuse to go through every entry in my time tracker to figure that out. My guess is at least 500. But that number doesn’t really matter to me, because all of the writing-related things are important for me as a writer.

How in the world did I get in 1000 hours?

In years when I was writing 400 hours per year, it was because I fought tooth and nail to spend a solid hour a day working on my writing. It took sacrifices–reading less, watching less, cleaning less, waking up early or staying up late, and sometimes insane life-juggling to carve out that hour.

Writing 1000 hours this year was actually easier than writing 400 those years, because of a very particular set of life circumstances:

- In September, my youngest child entered full-day kindergarten, but I did not start working full-time. Instead I got a 10-hour-a-week part-time job.

- From January to June, I was a stay-at-home parent with one 5-year-old at home. She was rather independent. I also gave her movie time for 2 hours every afternoon, and I always used it for writing time.

- Our family finances work on only my husband’s salary, which is a privilege that many incredible writers don’t have. I can put 1000 hours into writing even if I’m not going to make much from it.

If life has taught me anything, it’s that I can’t guarantee what my life circumstances will look like in any given year. Maybe I will have years in the future where I can spend 1000 hours writing, maybe I won’t. But it was fun to achieve that completely arbitrary benchmark this year.

What to Look for From Me in 2022

- March 1: The True Confessions of a London Spy (Mary Bennet 2) will be released

- May 13-14: I will be teaching a class called “In Defense of Writing Slowly” at the Storymakers conference in Utah

- September: The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception (Mary Bennet 3) will be released

Hopefully I will be able to add some more in-person events to this list

My Goals for 2022

- Finish revisions on The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception

- Actually finish revisions on an old steampunk novel (this is a goal I had for 2021 that I didn’t meet)

- Write at least the first draft of a new book (I have a few ideas for this)

I may add or subtract goals from this list as the year progresses.