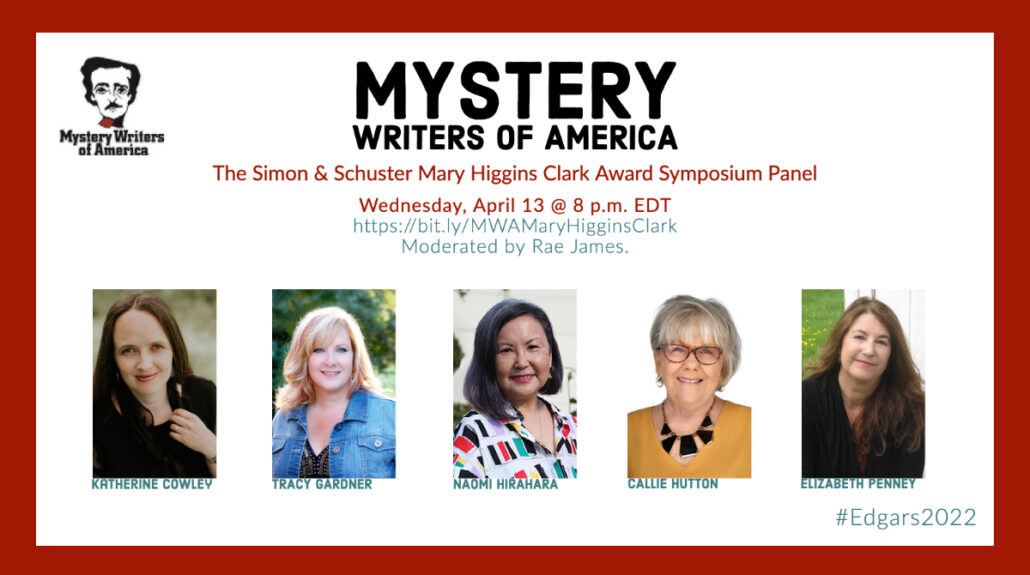

Free Upcoming Event: Mystery Writers of America Symposium

This year, in advance of the Edgar Awards, Mystery Writers of America is holding a virtual symposium.

I will be part of a panel with other nominees for the Mary Higgins Clark Award. I feel really honored to be talk about mystery novels with these amazing authors.

The event is free for anyone to attend. All you need to do is register in advance: https://bit.ly/MWAMaryHigginsClark

Researching The True Confessions of a London Spy in London

One of the best parts of writing The True Confessions of a London Spy was visiting London.

I wrote a somewhat sparse first draft of London Spy during the second half of 2018. And then, in October 2019, I had the opportunity of a lifetime. I got to visit London.

While this was largely a family vacation, I coopted parts of the trip for research. There were places in London that I knew were going to be in the book, and I had to visit those places, as well as museums and historic buildings that I knew would help me with my research. A few months later, as I wrote the second draft of the novel, I ended up needing a few new settings for key scenes. I ended up choosing places that had an impact on me during the London trip.

Exhibit A: The Monument to the Great Fire

Because of all the other buildings, it is difficult to get a good picture of the Monument to the Great Fire.

Me, next to the bottom of the Monument. Picture by one of my children.

Why I Chose The Monument

I knew that the Monument to the Great Fire would be important even before I wrote the first draft of the novel. So much of London—its architecture, its culture, its people—was influenced by the destructive 1666 fire. In 1814, when my book was set, this monument still acted as a symbol to the city—a symbol of what was lost, a symbol of tragedy, a symbol of change.

In the book, I needed Mary to be at a setting that was close the old (now no-longer existent) Customs House, and I chose the Monument because of the symbolism for London, and how this symbolism relates to her own story. I’ll avoid spoilers, but I will say:

Who we are is intrinsically connected to the difficult things that happen to us: these challenges and tragedies become interwoven into the fiber of our being. These moments transform us, and not always in a clear way. It’s not a net good or net bad change. But you can’t go to the past and swoop in and erase what happened, or you would have a completely different city, a completely different person.

Me, at the top of the Monument, contemplating whether Mary Bennet would actually choose to climb the 300+ steps to the top. I considered adding this climb to the second draft, but decided against it.

Descending the steps of the Monument to the Great Fire. Carrying 3-year-olds is a great workout, even when going down.

Exhibit B: Other London Sites

To see the individual captions, click the expand button on one of the photos.

Many of the stereotypical visuals that we associate with London did not exist in 1814: Big Ben, the Tower Bridge, and the Eye. Others did exist–like St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Tower of London–but didn’t end up in the book.

A lot of what was useful was being able to walk through the London streets and experience the flavor of the city. I spent a lot of time walking along the River Thames and picturing what it would have looked like in 1814, covered in ice.

One of my big priorities for the trip was visiting the Museum of London. As you go through the museum, you walk through different eras of London’s history. I may have spent an excess amount of time in the 1600-1900 section. There was clothing, fans, models of houses, and scientific devices. One of the exhibits was a reconstructed section of Victorian streets and shops. While that postdates The True Confessions of a London Spy by a few years, it wasn’t that different than it would’ve been in the Regency period.

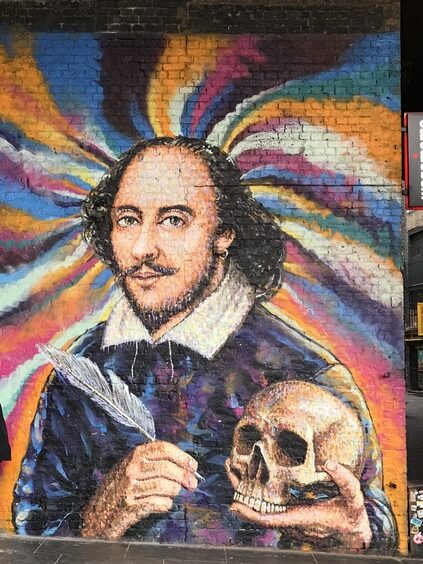

Exhibit C: Shakespeare in London

The first draft of the novel was about half the length of the final novel. It had plenty of subplots, but no plot, and it was missing a number of key characters. As such, in the second draft I had to add a plot, a number of characters, and plenty of new chapters and scenes. Which meant that I also had the opportunity to incorporate additional London settings.

One of the things that struck me during our visit to London was how much Shakespeare was part of the fabric of the city.

A Shakespeare mural in London. Picture by my husband, Scott Cowley.

I’ve loved Shakespeare since my junior year of high school, when an amazing English teacher introduced me to Hamlet and we watched Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead performed live. After my London trip, as I worked on building the character of Alys Knowles, I realized that I wanted Alys to love Shakespeare—this is her defining interest. During her life, Jane Austen read and attended Shakespeare plays, and she makes Shakespearean references in a number of her novels, so I thought it would be fitting.

Even though readers don’t meet the character of Alys Knowles in scene until the end of The True Confessions of a London Spy, Shakespeare became woven throughout the story, a lens through which to perceive relationships and interactions.

As I built up to the scene between Alys Knowles, Mary Bennet, and Fanny Cramer, I realized that I wanted the setting to have a connection to Shakespeare.

I considered placing the scene at Southwark Cathedral—this was the area where Shakespeare had lived, after all, it was near where the Globe had been located, and the cathedral predated Shakespeare by centuries.

One of my favorite parts of visiting Southwark Cathedral was seeing the stained glass window commemorating Shakespeare, but when I did some research, I realized that the stained glass had been added too late.

However, I liked the idea of using a religious edifice with a Shakespearean connection, because of the sense of immortality that gives. Which made me think of another place I had visited in London: Westminster Abbey.

Westminster Abbey is like walking among a who’s who of famous British dead people, and while Shakespeare was buried in Stratford-upon-Avon, there is a full-life marble statue of him in the Poets’ Corner. I realized that this was the public, safe spot that Alys Knowles would choose for a meeting.

While it is very possible to write a book without visiting the setting, and I have a number of research techniques that I’ve used when visiting a place is not an option, it truly was a remarkable experience to be able to visit London while writing a book set in London. London is one of my favorite cities, and I certainly plan to visit again.

#54: When to Summarize Dialogue

A common writing aphorism is “show don’t tell.” When it comes to dialogue, it is often powerful to show the dialogue in its entirety: to hear what the characters say and how they say it.

Yet while Jane Austen is a master of dialogue, there are countless moments throughout her novels when she chooses to summarize dialogue rather than showing it in scene.

Jane Austen summarizes dialogue when doing so better serves her storytelling purposes.

To consider what purposes summarizing dialogue could serve, let’s analyze a scene from Northanger Abbey.

Near the end of Northanger Abbey, Catherine Morland is unceremoniously thrown out of Northanger Abbey by an angry General Tilney. When she arrives home, she tells her family what happened. Soon, they meet up with her friends, the Allens, and they too must hear the story.

What is interesting in this passage is that Jane Austen does not show us the full scene. Instead, she intermixes telling (in this case through summary) with showing.

In the first paragraph of the scene, Austen summarizes the entire interaction, giving a bird’s eye view of what occurred, with narrator interpretation. Then we are brought to near the beginning of the scene in order to hear Catherine’s mother, Mrs. Morland, tells the story, giving her dialogue line by line.

[Catherine] was received by the Allens with all the kindness which her unlooked-for appearance, acting on a steady affection, would naturally call forth; and great was their surprise, and warm their displeasure, on hearing how she had been treated—though Mrs. Morland’s account of it was no inflated representation, no studied appeal to their passions. “Catherine took us quite by surprise yesterday evening,” said she. “She travelled all the way post by herself, and knew nothing of coming till Saturday night; for General Tilney, from some odd fancy or other, all of a sudden grew tired of having her there, and almost turned her out of the house. Very unfriendly, certainly; and he must be a very odd man; but we are so glad to have her amongst us again! And it is a great comfort to find that she is not a poor helpless creature, but can shift very well for herself.”

The summary at the start of the paragraph frames the conversation—it tells us what happened, and what to look for in the responses. It also offers insights into their characters, particularly in light of how they react in response to what is a plain, unstudied account of the events. Then we see, in scene, the exact four sentences of dialogue that Mrs. Morland used to tell the story.

This paragraph is followed by another paragraph of mostly summary. When there are direct quotes, they are statements that the characters say multiple times, and their inclusion is used as an example of the type of response that Mr. and Mrs. Allen make:

Mr. Allen expressed himself on the occasion with the reasonable resentment of a sensible friend; and Mrs. Allen thought his expressions quite good enough to be immediately made use of again by herself. His wonder, his conjectures, and his explanations became in succession hers, with the addition of this single remark—“I really have not patience with the general”—to fill up every accidental pause. And, “I really have not patience with the general,” was uttered twice after Mr. Allen left the room, without any relaxation of anger, or any material digression of thought.

The conversation then turns to Mrs. Allen’s recollections of Bath. This conversation is shown in scene, with each line of dialogue included by Austen. Mrs. Allen explains that she had her gown with Mechlin lace mended, and then she elaborates on their experiences in Bath and the Assembly rooms. To each statement, Catherine gives only short responses, because this conversation is bringing to mind her love interest, Mr. Henry Tilney, which also reminds her that Henry’s father, the General, has just thrown her out.

In the next two paragraphs we have dialogue from Mrs. Tilney on Bath, followed by a sentence of dialogue summary, followed by more dialogue from Mrs. Tilney:

“It was very agreeable, was not it? Mr. Tilney drank tea with us, and I always thought him a great addition, he is so very agreeable. I have a notion you danced with him, but am not quite sure. I remember I had my favourite gown on.”

Catherine could not answer; and, after a short trial of other subjects, Mrs. Allen again returned to—“I really have not patience with the general! Such an agreeable, worthy man as he seemed to be!”

The summary phrase is of note: Catherine could not answer and after a short trial of other subjects. The use of summary here emphasizes that Catherine is struggling to hold this conversation, because everything connects back to the Tilneys. Mrs. Allen tries introducing other subjects—and the exact subjects they try speaking about are not included, because they aren’t actually relevant to the story. But summarizing the fact that she tries various conversation topics shows how very difficult this is for Catherine—the Tilneys are what dominates her mind, and it is difficult for her to speak of them, but also difficult for her to speak of anything else.

There are a number of reasons to summarize dialogue rather than to show it in scene.

The most common reasons Austen summarizes dialogue:

- To show the passage of time.

- To condense unimportant dialogue.

- To focus the reader on the most important dialogue.

- To give interpretation of the dialogue, and provide commentary on the scene.

- To draw us into the lens and perspective of the narrator OR to draw us into the perspective of the character.

Whenever I am writing a scene where the dialogue is not quite working, one of the questions I ask myself is: Would part of this dialogue be more useful if it was conveyed through summary? Summarizing dialogue is another useful tool that can be used to powerful effect.

Exercise 1: Write a short scene that consists largely of dialogue between two characters. However, there’s a catch. For one of the characters you can include the dialogue, but for the second character, you can only summarize their dialogue. Try to give a feel for the second character’s dialogue and its effect even though you cannot include the dialogue itself.

Exercise 2: In film, dialogue is rarely summarized: because of the conventions of the medium, it is almost always shown in scene. Find a dialogue-heavy scene in a film and rewrite this scene in prose. Include a significant portion of the lines of dialogue exactly as they were stated in the film, but then summarize other sections of the dialogue. What effects does this summary create? How is summarizing some of the dialogue useful?

Exercise 3: Take a draft that you have written and analyze the dialogue. Are there any full scenes of dialogue you could eliminate and replace with a summary? Are there scenes of dialogue where it would be advantageous to replace a small or large part of the dialogue with summary? Find at least one spot in your draft where dialogue summary would be useful and revise.

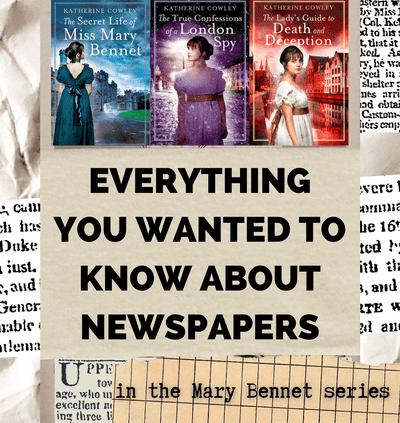

Everything You Wanted to Know About Newspapers in the Mary Bennet Series

Some of the most common questions I get about The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet and The True Confessions of a London Spy relate to the epigraphs at the start of each chapter:

- Are they from real newspapers?

- What inspired you to include these epigraphs?

- What purpose do they serve?/ What do they mean?

- How did you find them?

In this post, I’m going to give readers the answers to each of these questions.

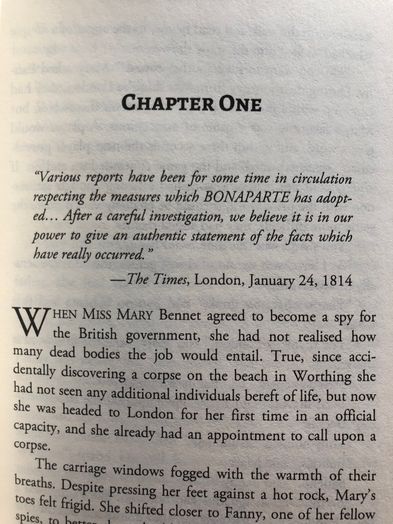

The first page of The True Confessions of a London Spy, with an epigraph from The Times

Are they from real newspapers?

Almost all of the passages are real excerpts from real newspapers, with the exception of three headings in Secret Life and two headings in London Spy. In the upcoming third novel, The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception, only one is from my own imagination, and one is from a letter instead of a newspaper.

What inspired you to include these epigraphs?

I loved the short newspaper excerpts at the start of each chapter in Mary Robinette Kowal’s alternate history science fiction novel The Calculating Stars, and I thought that they would fit well in my own story.

What purpose do they serve? What do they mean?

The newspaper excerpts do a number of things:

- Historical underpinning: unlike Jane Austen’s contemporary readers, most of us today don’t know the full historical context of the Regency. I wanted to Mary Bennet to solve mysteries that deal directly with the historical events and social issues of the day, and including these excerpts helps provide that context for the reader. For example, I wanted to establish the widespread dread of Napoleon Bonaparte, which is clearly present in the newspapers.

- Mary and other spies read a lot of newspapers: In the books, Mary, Lady Trafford, and other characters read numerous newspapers. I wanted to give a sense for some of the stories they encounter.

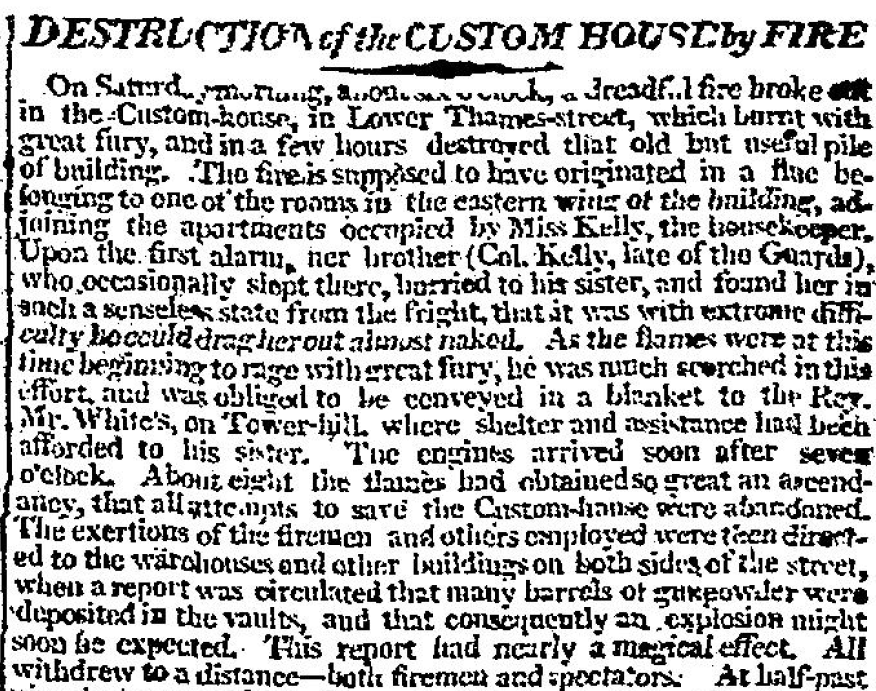

- Direct commentary on the content of the chapters: Because I use real historical events in the novels, many of the newspapers made direct commentary on these events. For example, in The True Confessions of a London Spy, the account that The Times made of the customs house explosion is devastating, and in the third novel, The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception, I wanted to showcase some of the alternative viewpoints on the war that aren’t held by the main characters of my story.

A portion of the first article in The Times about the Custom House fire, printed on February 14, 1814

- Parallels and Alternate Experiences: Some of the epigraphs are not specifically connected to any of the events, but they create parallel narratives and showcase alternate experiences. For instance, in each of the books I include excerpts about women in disguise or as spies. In London Spy, the weather acts as a sort of character and so receives a number of newspaper excerpts.

- Other Purposes: At times the newspaper excerpts are in conversation with the subtext of the novel, deal with the themes of the book, or add humor or satire to elements of a chapter.

How did you find the excerpts?

For each of the books, I waited until at least the third draft to start looking for newspaper headings. I needed the overall story to be mostly solidified, and I wanted the date each chapter occurred to be relatively fixed.

I used two newspaper subscriptions: a personal subscription to the British Newspaper Archives (which has digitized hundreds of newspapers), and a university subscription to The Times.

The tricky part is that computer programs have a hard time reading old newspapers, some of which were not well preserved. If you do a search in the British Newspaper Archives for the name Napoleon or Bonaparte in the year 1814, you’re lucky if the computer program finds 10% of the actual references. (It also doesn’t help that some of the newspapers wrote his name as Buonaparte to try to delegitimize his rule.). Most of the time instead of searching, I would download half a dozen different newspapers for a given day and read them.

Sometimes I had something very specific in mind that I was looking for—I was looking for a news story Bonaparte, crime, the stock exchange, the or the Viennese Waltz, or the weather. Yet most of the time I didn’t have a specific type of news in mind. Instead, I would read the articles with a sense of discovery, letting myself wander to columns or advertisements that drew my attention, and finding endless connections to my book. Sometimes I would find the perfect article quickly; other times I would choose three or four possibilities and then consider which really had the effect I wanted for the chapter, and fit the overall arc of the epigraphs.

I quickly got a good feel for different newspapers of the news, which ones were liberal or conservative, had the most interesting ads, included a regular fashion column, published poetry, or wrote the best opinion pieces. There was also a variety of different formats—while many of the newspapers only printed ads on the first page, others included articles from the start. Newspapers would reprint articles from other papers, and sometimes the news would be about events weeks or months in the past, depending on how long it took the information to reach England’s shores.

Sometimes I shifted the dates and timeline for a book because I really wanted to use as particular newspaper heading. And I definitely revised numerous details in the chapters because of things I learned through reading the newspapers—for example, in London Spy, Kitty’s reference to ice skating in Hyde Park came from a newspaper reference.

I have now read hundreds of newspapers from 1813, 1814, and 1815, and I feel like doing so has not only helped my books, but made me a more interesting person at parties—after all, who doesn’t want to hear 1814 trivia?

More About My Journey with Newspapers

All this newspapering has influenced my readings of other Jane Austen texts.

- I was recently a guest on the podcast The Thing About Austen, talking about Anne’s newspapers in Persuasion.

- I wrote a post for Jane Austen’s World about how 1814 newspapers should impact our reading of the snow scene in Emma.

I also did a guest post on My Favorite Bit, talking about some of my favorite newspaper excerpts.

Coming Soon!

Next week, on this blog, I’ll be posting about my trip to London and how that influenced the setting of The True Confessions of a London Spy. I’ll also be showing some of the actual dresses that were influences for Fanny’s designs. So come back to the blog, keep a watch on social media, or subscribe to my newsletter!

#53: Creating Space for Writing

One of the most common questions I am asked about my writing is, “When do you write?” I’m also asked, “How do you get writing done with children?” or “How do you prioritize writing when there are other important responsibilities?”

Part of writing is understanding your process, and what it takes for you to be able to write. This is something that Jane Austen seems to have thought a lot about. On September 8, 1816, she wrote a letter to her sister Cassandra which included the following paragraph:

I enjoyed Edward’s company very much, as I said before, and yet I was not sorry when Friday came. It had been a busy week, and I wanted a few days’ quiet and exemption from the thought and contrivancy which any sort of company gives. I often wonder how you can find time for what you do, in addition to the care of the house; and how good Mrs. West could have written such books and collected so many hard words, with all her family cares, is still more a matter of astonishment. Composition seems to me impossible with a head full of joints of mutton and doses of rhubarb.

Company and a busy week made writing more difficult for Jane Austen. She needed time for herself, time for quiet, and time without too many obligations. Especially in her years living in Chawton, Jane’s family did much to lift some of her responsibilities in order to give her the time and the mental space for writing.

Jane also prioritized a physical space. She had her own little table, just for her. And when I attended a guided virtual tour of her Chawton house a few weeks ago, the guide explained that several of the windows by the road were boarded up, so she wouldn’t have all the passerbys on the road looking in on her and distracting her.

In the letter, Jane is astonished by Mrs. West, who balances books and family cares: “Composition seems to me impossible with a head full of joints of mutton and doses of rhubarb.”

Most of us have things we need to balance, whether it’s family obligations, a full or part time job, school, or endless other responsibilities. These things are part of our lives. They’re not going to go away. But are we letting our heads be full of joints of mutton and doses of rhubarb? Or are we finding some time that is just ours, where we can let everything else go and give space for creativity?

When my children were pre-school age, I used nap time and movie time just for writing. It didn’t matter if there was a pile of dishes in the sink or a mess on the floor, appointments to schedule, or seemingly-urgent needs. This was my time, no matter what, and I wouldn’t let it be filled with mutton or rhubarb or anything else.

At other times, I’ve done #5amwritersclub so I could write before my mind filled with any other obligations. I’ve worked in coffeeshops. I’ve prioritized attending writing group.

We all have times, like Jane Austen, where we have obligations that prevent us from writing. But it’s important to make space for writing, whether it’s an hour a day, one evening a month, or a weekend retreat twice a year.

I have a variation on the standard writing exercises today—these are more personal reflections, about your personal writing spaces. But first, a few personal writing notes. I wrote an essay on revising for tone for Women Writers, Women[’s] Books. And yesterday, my second novel was released, The True Confessions of a London Spy! It’s exciting to have a new book to share with readers and friends.

Exercise 1: Spend a few minutes reflecting on the spaces you have for writing in your life. What gives you mental, physical, and creative space for writing. Do you prioritize giving yourself this space? What is something you could change to help create better spaces for writing in your life?

Exercise 2: Speak to the people in your life about your writing. How do you support the people in your life in their goals? How do they support you in your creative endeavors? Would any adjustments help you better support each other.

Exercise 3: Make a list of the priorities in your life, the things that matter to you, the things that pay the bills, the things that are essential. The goal is not to feel guilty that you have other responsibilities that are not writing. The key is to consider what things truly matter to you most, to give yourself credit for those things and to find meaning in those things. Sometimes non-priority things can be eliminated or shifted to give more space for your key priorities.

#52: Different Responses to Dialogue

One of the most useful practices when writing dialogue is to consider how different characters will respond to the same line of dialogue in different ways. Whenever, we have certain expectations for how we will be interpreted, for how we would like others to respond. Sometimes, they respond in the way we would expect; other times they respond differently. In a group dialogue, with three or more people, there can be—and often should be—a diverse range of responses to key lines of dialogue.

In Jane Austen’s novel Persuasion, Louisa Musgrove falls on a stone staircase and injures her head. Her illness and her recovery become a talking point in many social gatherings. Not long after the injury, Lady Russell and Anne Elliot call upon the Crofts. Jane Austen describes the conversation between Lady Russell, Anne, and Mrs. Croft, as Admiral Croft observes and then adds his perspective on the matter:

As to the sad catastrophe itself, it could be canvassed only in one style by a couple of steady, sensible women, whose judgments had to work on ascertained events; and it was perfectly decided that it had been the consequence of much thoughtfulness and much imprudence; that its effects were most alarming, and that it was frightful to think, how long Miss Musgrove’s recovery might yet be doubtful, and how liable she would still remain to suffer from the concussion hereafter!—The Admiral wound it all up summarily by exclaiming,

“Ay, a very bad business indeed.—A new sort of way this, for a young fellow to be making love, by breaking his mistress’s head!—is not it, Miss Elliot?—This is breaking a head and giving a plaister truly!”

Admiral Croft’s manners were not quite of the tone to suit Lady Russell, but they delighted Anne. His goodness of heart and simplicity of character were irresistible.

Lady Russell does not approve of Admiral Croft’s statement or the manner in which he has said it—to her, Louisa’s injury is not a laughing manner. This is not a formal, sophisticated way to speak of it. Yet we read that this response “delighted Anne.” It is not that Anne disregards propriety, but rather that she sees a place for levity, and that she understands his goodness and his character and how that informs his statement.

In a previous Jane Austen Writing Lesson, I discussed how groups of characters are not monoliths: even among very similar characters, there should be a range of perspectives and attributes.

The same is true with how characters respond to dialogue.

Factors that influence how a character responds to dialogue:

In Mansfield Park, a group of individuals, which includes most of the main characters, is given a tour of the Rushworth home by Mrs. Rushworth. Mrs. Rushworth show them the chapel—which disappoints Fanny for its lack of grandeur—and explains:

“It is a handsome chapel, and was formerly in constant use both morning and evening. Prayers were always read in it by the domestic chaplain, within the memory of many. But the late Mr. Rushworth left it off.”

Miss Crawford interprets this dialogue very differently than Fanny:

“Every generation has its improvements,” said Miss Crawford, with a smile, to Edmund….

“It is a pity,” cried Fanny, “that the custom should have been discontinued. It was a valuable part of former times. There is something in a chapel and chaplain so much in character with a great house, with one’s ideas of what such a household should be! A whole family assembling regularly for the purpose of prayer is fine!”

The differences in their reactions to Mrs. Rushworth’s dialogue reveal much about Miss Crawford and Fanny. Fanny is pious and has grand visions of morality, while Miss Crawford is more cynical.

Yet the dialogue does not stop there—each of the characters continue to bring themselves to the discussion. Fanny’s statement is immediately interpreted in two different ways:

“Very fine indeed!” said Miss Crawford, laughing. “It must do the heads of the family a great deal of good to force all the poor housemaids and footmen to leave business and pleasure, and say their prayers here twice a day, while they are inventing excuses themselves for staying away.”

“That is hardly Fanny’s idea of a family assembling,” said Edmund. “If the master and mistress do not attend themselves, there must be more harm than good in the custom.”

Miss Crawford’s interpretation shows an awareness of class disparity and the way in which upper class people often force their morality on those in their employ while disregarding the same principles of morality for themselves. It’s both a clever and an insightful comment. And it also treats Fanny’s perspective as inadequate and uninformed.

Edmund’s response defends Fanny, in part because of the long-established relationship that he has with Fanny, and his understanding of her meaning. But his response also stems from the fact that he intends to become a clergyman and also sees value in religious practices.

Later on in the scene, Edmund’s sister Julia tells a joke about Maria and Mr. Rushworth being ready for marriage, and tells Edmund:

“My dear Edmund, if you were but in orders now, you might perform the ceremony directly.”

Miss Crawford is shocked by this new information:

“Ordained!” said Miss Crawford; “what, are you to be a clergyman?”

“Yes; I shall take orders soon after my father’s return—probably at Christmas.”

Miss Crawford, rallying her spirits, and recovering her complexion, replied only, “If I had known this before, I would have spoken of the cloth with more respect,” and turned the subject.

This new knowledge makes Miss Crawford wish that she had responded differently to the previous lines of dialogue. She was trying to impress Edmund with her insights and clever way of speaking, but was missing information that would have shifted her response.

In writing group dialogue, it is useful to consider that different characters will often respond to the same passage of dialogue in different ways. Incorporating these differences can richer dialogue with more tension and movement.

Exercise 1: The Response Game

Choose 5 characters. These could be characters you’ve already written, characters from one of your favorite books or films (for example, Mr. Darcy, Mr. Bingley, Miss Caroline Bingley, Elizabeth Bennet, and Jane Bennet), or characters that are inspired by people in your life.

Now watch a trailer for a new or upcoming movie. How would each of the five characters respond differently to this trailer?

Craft a 2-3 sentence response for each of the characters to this movie trailer.

Exercise 2: A Practice Scene

Write a brief scene with three characters. Have one of the characters say a line of dialogue which is interpreted differently by the characters. something, and then the other two characters respond in different manners. The responses can be largely internal or largely external; they can be in the form of dialogue, action, or introspection. The characters may also have the same external reaction or action, but for different reasons.

Exercise 3: Dialogue Analysis and Revision

Part 1: Analyze a passage of dialogue in a published short story or novel. The passage of dialogue should include at least three characters. Consider when characters respond differently to the same line of dialogue, and what motivates this response.

Part 2: Revise a scene you have written which includes dialogue between at least three characters. Are there places where you could strengthen the passage by having the characters respond differently to the dialogue?