#13: Start the Story Early (If Necessary)

Most stories start not long before the inciting incident, providing a brief description, moment, scene, or a few chapters which encapsulate the period BEFORE—before everything changes for the characters. Emma and Persuasion provide good examples of this.

Other stories, like Pride and Prejudice, start after the inciting incident—in medias res.

Yet other stories take a very different approach to exposition and start long before the inciting incident disrupts the story (note that starting long before the inciting incident does not necessarily mean that the telling of the exposition needs to be long—expositions that start early can still be brief). Jane Austen uses this technique in two of her novels: Northanger Abbey begins at Catherine Morland’s birth, and Mansfield Park begins years before Fanny Price is born.

These two novels start the exposition early for two different purposes:

- Northanger Abbey: To show the main character’s life trajectory, and to contrast the inciting incident (and what comes as a result) against the character’s entire life.

- Manfield Park: To demonstrate a prior formative moment which caused a drastic shift in the main character’s life, and created a new normal, which is then disrupted by the inciting incident.

Life Trajectory in Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey demonstrates the main character’s life trajectory prior to the inciting incident. The novel begins with the line:

No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy, would have supposed her born to be an heroine.

After this establishment of theme (and the delightful, rather satirical approach of the entire novel), we learn of Fanny’s birth:

Her mother…had three sons before Catherine was born; and instead of dying in bringing the latter to the world, as anybody might expect, she still lived on—lived to have six children more…

We follow Catherine Morland’s childhood, learning that she prefers cricket to dolls, seeing her disinterest in learning and watching her quit music after only a year or instruction. The narrator jumps from Catherine at age ten to age fifteen, and we see her continued development:

To look almost pretty is an acquisition of higher delight to a girl who has been looking plain the first fifteen years o her life, than a beauty from her cradle can ever receive.

Catherine reaches seventeen, with nothing to interrupt the path that she is on, a point that the narrator draws attention to:

She had reached the age of seventeen, without having seen one amiable youth who could call forth her sensibility; without having inspired one real passion, and without having excited even any admiration but what was very moderate and very transient. This was strange indeed!

All this in the first chapter. By creating a life trajectory, it establishes a shared set of reference points with the reader, reference points that help us understand the main character and who she is prior to the inciting incident. These references are essential, because without them, we would be unable to understand Catherine’s choices throughout the novel—her life trajectory informs her naivety, her desire to be liked, her fascination with new people and places, and how she constantly turns to books as an escape.

The last paragraph of the first chapter establishes the inciting incident, which is placed in direct contrast with the main character’s life to this point:

[Mrs. Allen], a good-humoured woman, fond of Miss Morland, and probably aware that if adventures will not befall a young lady in her own village, she must seek them abroad, invited her to go with them.

The other benefit of this approach to exposition is that it allows the narrator to avoid infodumps later—it would be difficult to include all of these details as backstory later in the story without unnaturally piling them on.

The elements included in Northanger Abbey are referred to again and again throughout the story, both directly and indirectly. By journeying with Catherine from her birth to age 17, we are prepared for the much bigger journey she will take throughout the novel.

Prior Formative Moment/Shift in Mansfield Park

While the exposition of Mansfield Park covers a lot of ground, the main purpose is for us to experience a formative moment, a huge shift, in Fanny Price’s early life.

Manfield Park starts before Fanny’s birth, and focuses on the weddings of the prior generation. Three sisters become, respectively, Lady Bertram, Mrs. Norris, and Mrs. Price. Mrs. Price is the one whose marriage has disappointed her family by being beneath her station. Mrs. Price loses contact with her family, and only reestablishes it when expecting her ninth child. At this point, her oldest daughter, Fanny, is nine years old, and is about to experience a cosmic shift, caused by her aunts, Lady Bertram and Mrs. Norris, and her uncle, Lady Bertram’s husband, Sir Thomas.

Mrs. Norris was often observing to the others, that she could not get her poor sister and her family out of her head, and that much as they had all done for her, she seemed to be wanting to do more: and at length she could not but own it to be her wish, that poor Mrs. Price should be relieved from the charge and expense of one child entirely out of her great number. “What if they were among them to undertake the care of her eldest daughter, a girl now nine years old, of an age to require more attention than her poor mother could possibly give? The trouble and expense of it to them, would be nothing compared with the benevolence of the action.” Lady Bertram agreed with her instantly. “I think we cannot do better,” said she, “let us send for the child.”

Sir Thomas is initially resistant the idea but is won over by his sister-in-law and wife. As the scene continues, we come to understand the character of these three adults, and without having met Fanny, we know intuitively that this is not going to be a warm, welcoming place for her.

We meet Fanny in Chapter 2, as she begins her “long journey.” We are with her throughout this epic change; we feel her discomfort as she is introduced to the family, and we see into her mind and character:

Her consciousness of misery was therefore increased by the idea of its being a wicked thing for her not to be happy.

Fanny struggles on and on. Through her eyes, we see how inferior she feels compared to her cousins, and how unrefined. In this exposition, we also come to know, in more depth, one of the other key characters of the novel, Edmund Bertram.

A week had passed in this way, and no suspicion of it conveyed by her quiet passive manner, when she was found one morning by her cousin Edmund, the youngest of the sons, sitting crying on the attic stairs.

“My dear little cousin,” said he, with all the gentleness of an excellent nature, “what can be the matter?”

A touching scene follows in which Edmund helps Fanny share her thoughts. He comes to learn about her family and her relationships with her siblings. He also helps her write and send a letter, promising she will not have to pay for it. This first real moment between Edmund and Fanny sets up their entire relationship, which is such a huge part of the novel, and it is better experienced in scene rather than through summary or flashback.

Thus, in chapter 2, we experience this great upheaval in Fanny’s life, and we see her adjust to the new normal, the new status quo.

If there has been a formative moment, a grand shift in a character’s life, there is power in allowing the reader to experience it with the main character. If this sort of shift merits being part of the exposition, it is typically large enough that in a different story it could be the inciting incident. Yet if used as exposition, it establishes a new normal, which is then disrupted by the inciting incident.

If Fanny’s removal to Mansfield Park was the inciting incident, the novel would be about ten-year-old Fanny and the internal and external journey she takes as she adjusts to her new life. Instead, this adjustment is covered in a single chapter, paving the way for the actual inciting incident, which is Mr. Norris’ death and the arrival of a new set of rather disruptive characters: Mr. and Mrs. Grant, Mr. Crawford, and Miss Crawford. These new characters disrupt not just Fanny’s life, but the lives of the entire family. But for Fanny, this disruption, this inciting incident, feels deeper, because this is not the first huge disruption she has experienced.

In Conclusion

In Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park, Jane Austen uses two of the major approaches for starting a story early: providing a life trajectory, and depicting a prior formative shift. Yet starting the story early is not the only good approach to exposition, nor should it be the default. In Persuasion there are several formative shifts for Anne prior to the start of the novel—her mother’s death and her short-lived engagement. Yet Anne’s experience of these moments is revealed effectively through backstory, and in fact, their placement later in the story serves to reveal Anne’s character and her regrets at key moments.

If you want to start the story early, there needs to be a good reason for us to experience these scenes with the character. This experience should be enlightening to us, and, like in Northanger Abbey and Mansfield Park, there needs to be a reason that they must be experienced at the beginning. We should start our stories early if it helps us understand the logic of everything else.

Exercise 1: Find another story—a book or a film—that starts early. Now analyze it. Is it painting a character trajectory? Is it showing a prior disruptive moment? Or is it doing something else entirely?

Exercise 2: Take one of your characters (or an idea you have for a character) and write a 500-word life sketch, that begins either before or at their birth. Once you’re finished, analyze the results:

- What new things did you learn about your character?

- What were the biggest, most defining moments in your character’s early life? What shaped them into who they are as they enter the story?

- Are there elements of your character’s early that should be woven into the story as backstory? Or is this a case where it would be useful to experience the character’s early life as part of the exposition?

Even if none of the life sketch is incorporated into the story, writing it is a useful practice that can help you understand your character, their personality, and their choices.

Exercise 3: Take a fairy tale or classic story that does not give many specific details about a character’s younger years (for example, Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice). Brainstorm specific events and incidents that could have occurred before the start of the story, and would be in keeping with their character, the story world, and what we do know.

#12: Start In Medias Res to Jump Into the Story

I have an unpublished novel that I wrote and revised years ago. It’s a pretty good story, but the beginning never worked. I tried starting it dozens of ways, establishing the exposition this way and that, and ultimately, I set the story aside. Now, as I look back on it, I realize that I was starting the story way too early. If I were to revise it again, I would start it much later, in medias res.

In medias res means, literally, “in the middle of things.” It’s a term originally used by Horace over 2000 years ago in his work Ars Poetica (Poetic Arts).

Basic plot structure demands that a story needs a Beginning, a Middle, and an End. But sometimes, a story does not actually need a Beginning. Or at the very least, it doesn’t need to start at the beginning.

Unlike Jane Austen’s other novels, which begin with paragraphs or chapters of exposition, establishing the characters and the world, in Pride and Prejudice, we begin in medias res. The inciting incident is that Mr. Bingley has joined the community—and this inciting incident occurs before the first page of the book. As we’ve previously discussed, inciting incidents disrupt the world of the characters, shaking them out of stasis and starting them on their journey.

In many cases, we need exposition before we can understand or appreciate how the world has been changed and its characters have been incited into action. Yet there are benefits to jumping straight into the heart of the story.

Benefits of starting a story in medias res:

-It immediately focuses the reader on the main stakes

-There is inherent excitement, energy, and movement in what comes after the inciting incident

-It avoids what could be (in certain stories) slow or unnecessary exposition

-It can create suspense to learn not just what will happen next, but also, what happened before

Chapter 1 of Pride and Prejudice

The first two paragraphs (beginning with the famed “It is a truth universally acknowledged”) are thematic, and provide commentary on society and the characters without providing true exposition. Then, starting with the third paragraph we read:

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

That was invitation enough.

We are brought immediately into the action of the novel, as Mrs. Bennet attempts to use all of her powers of persuasion to convince Mr. Bennet to call on Mr. Bingley so their daughters can be introduced to this newly-arrived, eligible bachelor.

Without need for straightforward exposition, we are introduced to things that would commonly be established in a more traditional exposition: the characters’ attributes and the importance to Mrs. Bennet of marrying her daughters.

“What is his name?”

“Bingley.”

“Is he married or single?”

“Oh! Single, my dear, to be sure! A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!”

“How so? how can it affect them?”

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.”

“Is that his design in settling here?”

“Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so! But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

If dialogue is used, as it is in this case, to give hints of exposition, it must seem natural that the characters would really say these things. The effectiveness of including these details derives from the fact that Mr. Bennet is attempting to annoy his wife and feign ignorance of her matrimonial plans.

Interestingly, we don’t actually see the main character—Elizabeth—in a scene until Chapter 2. In Persuasion, each of the three sisters is given a thorough introduction by the narrator, and then we meet them and see them in action. In Pride and Prejudice, we are not given a through exposition to establish the characters; we must learn of them on the way. In the first chapter, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet only specifically reference three of their daughters, and do so only briefly:

“I will send a few lines…to assure him of my hearty consent to his marrying which ever he chuses of the girls; though I must throw in a good word for my little Lizzy.”

“I desire you will do no such thing. Lizzy is not a bit better than the others; and I am sure she is not half so handsome as Jane, nor half so good humoured as Lydia. But you are always giving her the preference.”

“They have none of them much to recommend them,” replied he; “they are all silly and ignorant like other girls; but Lizzy has something more of quickness than her sisters.”

A Few Key Considerations for Beginning In Medias Res

If you’re going to start in medias res, the opening scene must be understandable without exposition or explanation.

If you’re starting in medias res, it still must be very clear how the inciting incident has changed the story world and set the characters on their journey.

And, perhaps most importantly, if you’re starting in medias res, you must avoid the temptation to infodump—to dump information, backstory, and exposition on the reader in order to provide them with what you think they surely need to know before experiencing your story.

Now, I’m going to rewrite a short portion of Chapter 1 of Pride and Prejudice, and I’m going to intentionally ruin it by adding too much backstory and exposition:

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his wife, Mrs. Bennet, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mrs. Bennet was a woman in her early forties, who often forced conversation on her husband.

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not, though this was not strictly true.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer. The surest way to annoy his wife—which was a source of endless entertainment for him—was to say nothing.

“Do not you want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. He had to listen to her, he had to act, for they had five daughters, and if Mr. Bennet died, they would lose the house and be thrown out on the streets. Maybe, the new tenant, Mr. Bingley, would marry one of their daughters and save them from this fate. Jane would serve well, as she was the oldest and most handsome, though the other four daughters would also be an acceptable solution, should Mr. Bingley be drawn instead to Elizabeth, Mary, Kitty, or Lydia.

Now that was a truly intolerable passage. If you start your story in medias res, don’t do that. Do it like Jane Austen did it.

Exercise 1:

Take a novel that you’ve never read, and start reading it several chapters in. Or, take a movie you’ve never seen and start at least 15 or 20 minutes in.

As you read or watch, how do you figure out what’s going on? How do you orient yourself? How did you learn about the characters, and what can you conclude about what happened previously?

Write about your experience doing this in the comments, and what this teaches us about starting in medias res.

Exercise 2:

Some stories that begin in medias res are nonlinear—they do not take a straightforward path through time, or in other words, they do use a sequential structure.

The most common nonlinear structure is to start in the middle of the story for the prologue or an opening chapter, then to leap back in time and tell the story from start to finish.

There are many stories that use more complicated nonlinear structures, moving us back and forth from what point to another. This requires a very close attention to craft, clues embedded in the narrative that keep the reader oriented within time (unless part of the point is to disorient them), and a purposeful approach to juxtaposing one scene with another.

Choose a story that you like to tell people about something that happened in your life—an embarrassing moment, how you met a significant other, etc. Now write down the story using a nonlinear—yet still cohesive—structure.

Exercise 3:

Take a short story or a novel that you’ve written that begins with exposition. Take a few minutes and experiment with reorganizing the story so it starts in the middle of things. How late could you start the story? What details can you weave in later?

#11: Use Exposition to Set the Stage

Soniah Kamal’s novel Unmarriageable, an incredible retelling of Pride and Prejudice in modern-day Pakistan, opens with Alysba Binat (our Elizabeth counterpart) teaching Pride and Prejudice at an English-speaking high school in Pakistan. In the beginning scene, she has her students—all female—write their own first lines inspired by the first line of Pride and Prejudice, their own “truths universally acknowledged.” As Alys leads the discussion, she brings up double-standards for men and women, explains that women’s independence is not a Western idea and has roots in their own culture, and raises the possibility that a woman’s sole purpose is not to marry and have children.

One of the ninth graders arrives late to class, a diamond engagement ring on her hand, and eventually the students turn the questions to Alys—why are you not married?

“Unfortunately, I don’t think any man I’ve met is my equal, and neither, I fear, is any man likely to think I’m his. So, no marriage for me.”

This scene sets up the core conflict of the novel—will Alys find her equal and eventually marry? It also sets up Alys’ personality, her quest to educate the young women of her community, and the cultural context in which she lives. In the first two chapters we also learn of her conflicts with the principal, information about her four sisters, how the family has lost their fortune and gotten into the financial straits that require the two oldest sisters to work, and we get a sense of the city and where it’s wealth and poverty are located. All this is so the stage is set, so that when the inciting incident disrupts Alys’ life and moves her on her journey (in the form of an invitation to a huge wedding where they will meet Bingla and Darsee), we as an audience are ready for it.

This is exposition, the setting of the stage for the story in order to provide important background information to the reader about the characters, their history, and their world.

As discussed in the lesson on plot structure and external journeys, the exposition shows the world in stasis, and it requires the inciting incident to launch the external journey of the plot and the internal journey of character transformation.

According to Oxford Languages, the word exposition comes from the Latin verb exponere, which means to “expose, publish, [and] explain.”

exponere = to expose, to publish, to explain

Good exposition should:

The first four paragraphs of Jane Austen’s novel Emma provide the exposition for the story. We begin with the opening line:

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.

This quickly paints an image of Emma’s character, her high place in society, and her general satisfaction with life.

In the second paragraph we learn the following, which brings up key details from Emma’s past and sets up the world and her place in it:

- Emma is the second daughter

- Her sister is married and gone

- She is mistress of the house (or basically, the female manager of it)

- Her father is “affectionate” and “indulgent”

- Her mother died when she was very young

- Her governess acted as a replacement mother figure in her life

That’s a lot for one two-sentence paragraph: Jane Austen manages to swiftly set the stage.

The third paragraph goes into more details on the governess, Miss Taylor, because these details will demonstrate the disruptiveness of the inciting incident:

- Miss Taylor has been with the family for 16 years

- She is more of a friend or sister figure than a governess

- She does not restrain or direct Emma (and has not for quite some time)

- “They had been living together as friend and friend very mutually attached, and Emma doing just what she liked; highly esteeming Miss Taylor’s judgment, but directed chiefly by her own.”

The fourth paragraph raises the themes and issues which will be explored throughout the story. In this case, it’s a look at the flaws in Emma’s character, and how these flaws will drive the narrative:

The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself: these were the disadvantages which threatened alloy to her many enjoyments. The danger, however, was at present so unperceived, that they did not by any means rank as misfortunes with her.

By the time we reach the fifth paragraph, all the essential details have been explained, and we are prepared for the inciting incident: Miss Taylor’s marriage.

We learn plenty of other details of backstory as the novel progresses—details about the past and about Emma’s relationships with others in her community—but these are not included in the initial exposition, because they are not essential for setting the stage.

Sometimes exposition—this setting of the stage for the reader—takes several chapters, as in the example of Unmarriageable. Other times, it takes a few paragraphs, such as in Emma. The next lesson will discuss stories that start in medias res, at the moment of the inciting incident, or sometimes even after the inciting incident, and address how exposition can be incorporated in small amounts as the story progresses.

Regardless of the manner in which the exposition is presented, it sets the stage for the story and orients the reader.

Exercise 1: In the beginning of Emma, Jane Austen uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. She sets forth the character, the world, and the situation through the perspective of a storyteller introducing her cast. The narrator is insightful and interesting, and is unafraid to comment on her characters and their attributes.

Brainstorm a new character by choosing and name and writing down three of their defining characteristics, attributes, or interests.

Set a timer for 15 minutes, and draft a brief exposition which uses an omniscient storyteller point of view. This should set the stage for the character and their world.

Exercise 2: In Unmarriageable, Soniah Kamal uses a close third person point of view. She includes the same sort of expository details as Austen does in Emma, but she reveals them through use of a scene. (Jane Austen does uses this approach—providing exposition through a scene—in some of her novels.)

Use the same character and characteristics/attributes/interests from exercise 1. Instead of sharing these details from a storyteller perspective, figure out how to reveal these details organically through a scene—have these demonstrated through the character’s actions or interactions. Set a timer for 15 minutes and write an opening scene that provides exposition.

Note: providing exposition through a scene is currently the most common approach in writing, though there are books still being published that open with the perspective of a storyteller setting the stage.)

Exercise 3:

Option 1: For a new story, brainstorm elements that may be useful for include in the exposition.

- Who is the main character?

- What about the character’s past informs who they are today?

- Who are the other key characters?

- What do readers need to understand about the world?

- What themes or issues could be raised that will be explored throughout the story?

- What details about the character and the world could be included in the exposition that will contrast and show the disruptiveness of the inciting incident?

Once you have brainstormed, consider what absolutely must be revealed in the exposition, and what can be revealed later. Most details about the character and the world can be revealed, piece by piece, later in the story, so choose what is both the most essential and the most interesting way to take us into the world and the perspective of the main character.

Option 2:

If you have already drafted a story, analyze what you included as part of the exposition. Label each detail with categories that could include things like “character attribute,” “character history,” “supporting character,” “relationship,” “worldbuilding,” “theme,” etc. Are there any details that could be saved for later in the story? Are any details that are missing that would demonstrate how the character’s world is disrupted by the inciting incident?

#10: Use a Reader-Writer Contract to Create a Satisfying Resolution

Andrew Davies’ Sanditon, a recent TV adaptation of Jane Austen’s uncompleted novel, aired in 2019 in the UK and 2020 in the US. It has been rather polarizing for viewers (the Twitter and Facebook arguments have been heated!). Among those who finished the series, there have been two major reactions: the first group is disappointed by the final episode, and the second group is ravenous for a second season. (Personally, I would love a second season—#SaveSandition.)

What unites both groups is a sense that the promises made at the beginning of the show have not yet been fulfilled. Whether that leads to disappointment or a desire for more so that the promises can be fulfilled (a Jane Austen heroine always gets her man!), it teaches an important principle of writing:

Audiences have expectations about what makes a satisfying conclusion or resolution for any given story, and these expectations are based on implied promises made by the writers of stories.

Note: many of these expectations are based on the standard plot structure discussed in Jane Austen Writing Lesson #4.

The Reader-Writer Contract

I first learned about the reader-writer contract in an introduction to film class that I took my freshman year of college. The principles, though, apply just as well to literature as to film.

The reader-writer contract is an agreement between the reader and the writer of a text.

The reader promises to suspend disbelief and invest their time and attention in the story. (Sometimes, the reader also makes a financial investment.)

The writer promises to weave an engaging, entertaining story that delivers on commitments made at the beginning of the story, including, but not limited to:

- Genre

- Plot

- Character

- Style

- Point of View

The Reader-Writer Contract of Jane Austen’s “A History of England”

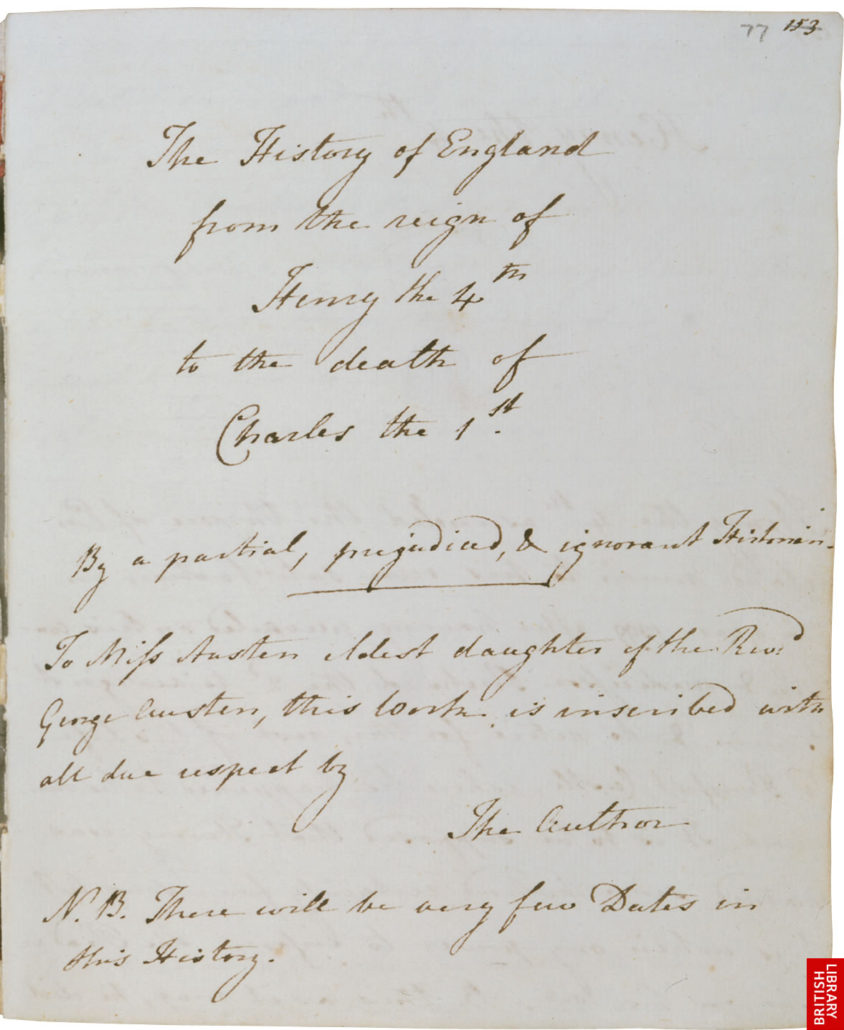

When Jane Austen was sixteen years old, she wrote a short nonfiction text called “The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the Death of Charles the 1st.” You can read it online or in book form. She did not write it with the intent of publishing it: like much of her juvenilia (her works written as a child/teen), the intent was to share and perform it with her family. “The History of England” was written in November 1791, when she was not quite sixteen years old.

We’ll examine the beginning of “The History of England,” consider how the reader-writer contract sets up its promises, and then look at how these promises are fulfilled to create a satisfying resolution.

The Title and Byline

The title page Jane Austen wrote by hand for “The History of England” (she copied this into her second notebook of writings from her youth, which can be viewed online at The British Library).

The full title of the piece is “The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the death of Charles the 1st.” This is a very standard title for a serious history written in the 1790s. Of course, immediately after the title comes the byline:

By a partial, prejudiced, and ignorant Historian.

Before the piece begins, we also receive this note:

N.B. There will be very few dates in this history.

Already, Austen has established genre expectations and tone: this is a parody of standard histories. This is not a text we should turn if we truly want to learn about British history. The admission that the historian author is “partial, prejudiced, and ignorant” is clever and immediately attracts us to the speaker—despite her alleged ignorance, we immediately want to know what she has to say.

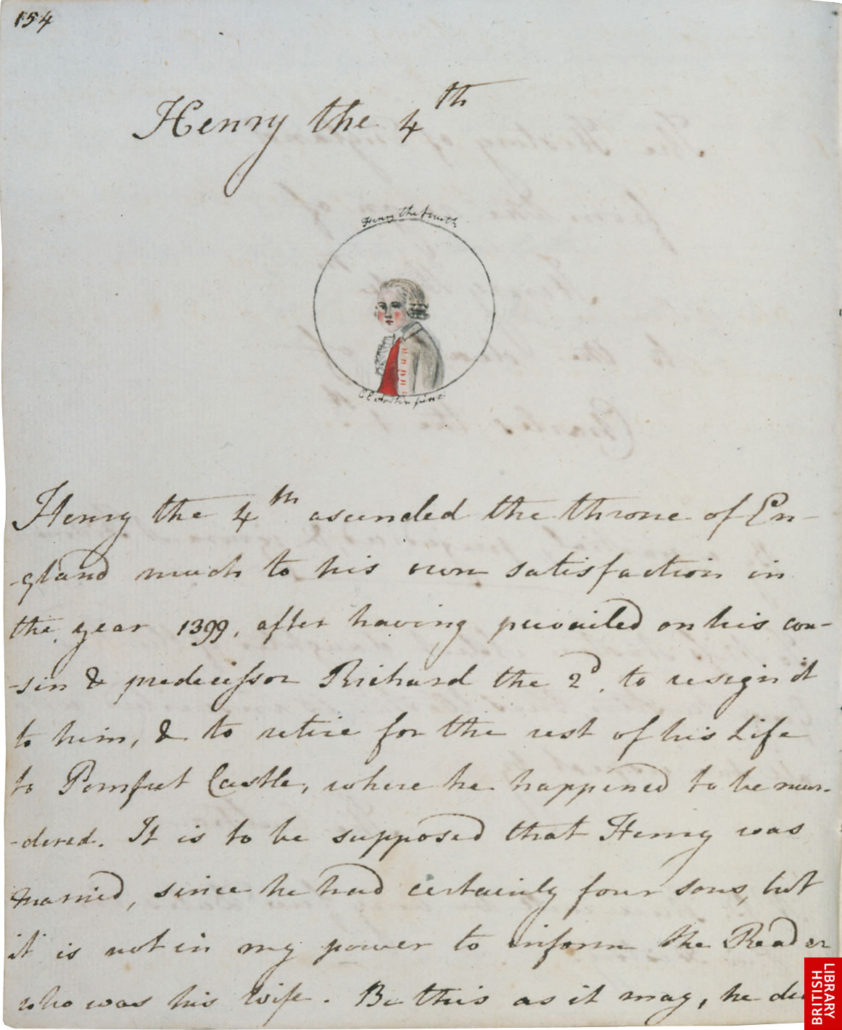

The First Paragraph

Another handwritten page by Jane Austen, from The British Library.

Jane Austen continues to establish the reader-writer contract in the first paragraph:

Henry the 4th ascended the throne of England much to his own satisfaction in the year 1399, after having prevailed on his cousin & predecessor Richard the 2d to resign it to him, & to retire for the rest of his Life to Pomfret Castle, where he happened to be murdered. It is to be supposed that Henry was married, since he had certainly four sons, but it is not in my power to inform the Reader who was his wife. Be this as it may, he did not live for ever, but falling ill, his son the Prince of Wales came and took away the crown; whereupon, the King made a long speech, for which I must refer the Reader to Shakespeare’s Plays, & the Prince made a still longer. Things being thus settled between them the King died, & was succeeded by his son Henry who had previously beat Sir William Gascoigne.

This firmly establishes the point of view of the speaker, her (intentionally) biased relationship with the subject matter, and the humor created as a result.

Promises Made and Kept

Swiftly, in the beginning of the piece, our expectations have been set, and the reader-writer contract has been forged. Here are a few of the promises that have been made:

- Genre: Parody/satire, with the effect of creating humor and commentary, both on these figures in history, and on the persona of a historian

- Plot: marriages, deaths, killings, and random details about a series of rulers from Henry the 4th to Charles the 1st.

- Character: the characters of the past are set forth, but the narrator herself seems to be a character

- Style: playful, amusing

- Point of view: first person, ignorant “historian” (not simply a reader, but someone making a claim that despite their ignorance, they still deserve the title “historian”)

These promises, having been made at the start, are kept and built upon throughout the piece.

A few of my favorite lines demonstrate this quite well:

“This unfortunate Prince lived so little a while that nobody had time to draw his picture.”

“Tho’ inferior to her lovely Cousin the Queen of Scots, [she] was yet an amiable young woman & famous for reading Greek while other people were hunting.”

“He was beheaded, of which he might with reason have been proud, had he known that such was the death of Mary Queen of Scotland; but as it was impossible that he should be conscious of what had never happened, it does not appear that he felt particularly delighted with the manner of it.”

The Satisfying Conclusion relies on these initial promises

In order for the conclusion of a story to be satisfying, it must fulfill the promises that it has made.

The following is the final paragraph of Jane Austen’s “History”:

The Events of this Monarch’s reign are too numerous for my pen, and indeed the recital of any Events (except what I make myself) is uninteresting to me; my principal reason for undertaking the History of England being to prove the innocence of the Queen of Scotland, which I flatter myself with having effectually done, and to abuse Elizabeth, tho’ I am rather fearful of having fallen short in the latter part of my Scheme. —. As therefore it is not my intention to give any particular account of the distresses into which this King was involved through the misconduct & Cruelty of his Parliament, I shall satisfy myself with vindicating him from the Reproach of arbitrary & tyrannical Government with which he has often been charged. This, I feel, is not difficult to be done, for with one argument I am certain of satisfying every sensible & well disposed person whose opinions have been properly guided by a good Education — & this argument is that he was a Stuart.

Austen maintains the genre, tone, point of view, etc., but she goes further: she takes the parody to its satisfying conclusion by throwing aside the cloak of a historian’s supposed neutrality, directly stating her skewed intentions, and closing with an unsupported, fallacious argument.

In Conclusion

Typically, the Reader-Writer contract should be established within the first 10-20% of a story. We need buy-in and commitment from our readers.

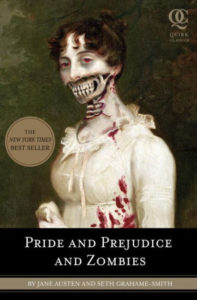

If you went to the movie theater to watch a romantic comedy and half-way through it transformed into a zombie film, you would probably walk out, unless there had been clues planted at the beginning of the film that a zombie film was coming.

Notice that the novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies begins to establish the contract of a not-so-traditional Jane Austen story through the cover and the opening line:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a zombie in possession of brains must be in want of more brains.”

While the contract should be established quickly, this doesn’t mean you have to give everything away at the beginning of the story. There can be plenty of twists and turns, grand reveals and surprises, new characters and subplots—in fact, readers expect these. But if there is a large shift, hints of it must be sprinkled near the beginning. And most importantly, to create a satisfying resolution at the end of the story, the resolution must fulfill the promises set up at the beginning of the story.

It’s like ordering at a restaurant. If you order a vegetarian meal, the meal better not have chicken in it. It’s fine to defy expectations, push genre limits, experiment and break rules, but you must be aware of the contract you are establishing with the reader, and if you want a satisfying conclusion, you must find a way to keep that contract.

Exercise 1: Choose a book, film, or TV show that you have never read or watched before—this should be new for you. Now read or watch the first 10% of the book/film/first episode.

Before you read or watch more, try to figure out the reader-writer contract for this story.

- What promises has the writer made?

- What is the genre, and how does the story treat the genre? (firmly in genre, parodying the genre, mix of two genres, etc.)

- What expectations do you have for plot and character?

- What is the point of view? What is the writer’s style?

Read or watch the rest of the story, and then evaluate how it met your expectations. Was the reader-writer contract kept? Was the story effective for you as a reader/viewer? Did anything defy what was established in the reader-writer contract, and if so, was it effective?

Exercise 2: Create a template Reader-Writer Contract that works for an entire category, genre, or subgenre of writing. Make sure that this category, genre, or subgenre is one that you write or would like to write.

Sample categories:

- Literary

- Genre fiction

- Poetry

- Creative nonfiction

Sample genres:

- Romance

- Science fiction

- Mystery

- Thriller

- Cooking

- Biography

Sample subgenres:

- Regency romance

- Urban fantasy

- Bildungsroman

- Popular history

- True crime

Once you have chosen a category, genre, or subgenre, make a reader-writer’s contract. Consider standard characteristics, plot expectations (some categories/genres have very fixed expectations for plot events, while the expectations are more loose for others), character, style, point of view, and anything else that might make up part of a standard reader-writer contract for this category/genre/subgenre.

Exercise 3: We expect large promises to be fulfilled—if the story is a romance, the main couple should be together by the end of the story. As readers and viewers, we also love it when small promises are fulfilled. If the character is searching for a good taco several times throughout the story, it’s going to be really satisfying if they get that good taco by the end of the story.

Consider one of your own stories, that you have either drafted or are currently planning.

What are tiny promises that either have been made or could be made near the beginning of the novel? (Think “good taco” level promises—this could be something related to the main character, a minor character, etc.)

How and where could these promises be fulfilled?

#9: Use Dialogue to Create Dynamic Interactions Between Characters

Dialogue is communication. connection. conversation. conflict. character.

Many of the most quoted Jane Austen quotes come from her characters’ dialogue. Personally, I find that the dialogue between her characters is always engaging and dynamic. She never uses it simply for one character to give information to another character (or to the reader): her dialogue always has a deep impact on the plot, on the characters, and on the subtext.

Consider this scene from her first published novel, Sense and Sensibility. The two sisters, Marianne and Elinor, are in London. Marianne is pining for a man named Mr. Willoughby. Many people assume that Marianne is engaged to Willoughby, but Elinor is unsure, and for chapters has not known how to ask her sister for the truth.

A note was just then brought in, and laid on the table.

“For me?” cried Marianne, stepping hastily forward.

“No, ma’am, for my mistress.”

But Marianne, not convinced, took it instantly up.

“It is indeed for Mrs. Jennings; how provoking!”

“You are expecting a letter then?” said Elinor, unable to be longer silent.

“Yes, a little—not much.”

After a short pause, “you have no confidence in me, Marianne.”

“Nay, Elinor, this reproach from you—you who have confidence in no one!”

“Me!” returned Elinor in some confusion; “indeed, Marianne, I have nothing to tell.”

“Nor I,” answered Marianne with energy, “our situations then are alike. We have neither of us any thing to tell; you, because you do not communicate, and I, because I conceal nothing.”

Elinor, distressed by this charge of reserve in herself, which she was not at liberty to do away, knew not how, under such circumstances, to press for greater openness in Marianne.

There are four core components that make this dialogue effective:

What the characters say

Sometimes two characters will have the same goal or objective for a conversation, but often, characters have different goals.

In this scene, Elinor’s primary goal is to discover the truth from Marianne so she can better help her sister. She takes the opportunity to question Marianne, inviting her to open herself up and confide in her. However, telling Marianne “you have no confidence in me” does not have the intended effect and puts Marianne on the offensive.

Marianne’s original goal is to conceal her anxieties about her relationship with Willoughby: she does not want her older sister’s judgment or advice. To this is added the goal of pointing out Elinor’s hypocrisy. She knows that Elinor, too, is keeping things from her, and while stating this does not lead to Elinor opening up to Marianne, it does achieve Marianne’s ultimate goal of ending the conversation quickly.

When characters have different goals for a conversation, it creates organic and compelling dialogue with forward movement and momentum. (This is true even if the characters have similar goals: character’s goals will never entirely overlap, and this will be reflected in what they say.)

How the characters say it

Most of how the characters are talking, such as their tone and their volume, is implied by the dialogue itself. For instance, the exclamation mark and the sentence structure indicate the way in which Marianne speaks the following line:

“It is indeed for Mrs. Jennings; how provoking!”

Skilled writers like Austen reveal most of how the characters speak by the speech itself, without relying heavily on description. Jane Austen does give several additional descriptions, such as cried Marianne, but if these sorts of qualifiers were used on every line, it would clutter and distract.

In this passage, Austen gives two more brief descriptions of how the characters are speaking: “returned Elinor in some confusion” and “answered Marianne with energy.” These descriptions occur in brief succession, and this contrasting pair paints a portrait of the two sisters, demonstrating even in this short moment how the sisters acts as foils to each other.

What the characters don’t say

In any conversation, there are a multitude of things left unsaid: motivations and emotions, backstory and baggage. Very few people are entirely open in conversation, even to those who are closest to them. (When characters are finally open with each other, it can create huge emotional resonance for readers.)

What the characters choose not to say has a huge impact on the dialogue. In this scene from Sense and Sensibility, the very subject of the conversation is what they refuse to tell each other. In addition to not talking about their secrets, they do not talk about how irritated they are with each other. This is fueled by their frustration with their situations, and a latent sense of hopelessness, especially for Marianne, but also for Elinor.

Often we see characters’ biggest desires and anxieties in what the characters choose not to say, or find themselves unable to say, and this can help create dynamic interactions.

What the characters do

Generally, actions are peppered throughout dialogue scenes, and are just as important as the words that people say.

In this scene, Marianne’s actions betray how much she is hoping for a letter from Willoughby. Her haste in stepping forward underlines her impatience and longing, and she cannot trust the word of the servant—she must pick the letter up herself to see that it is truly not for her.

Inaction can be as important as inaction. Note the power in Elinor’s pause before she makes her accusation:

“You are expecting a letter then?” said Elinor, unable to be longer silent.

“Yes, a little—not much.”

After a short pause, “you have no confidence in me, Marianne.”

This pause provides a space for Elinor to decide to push the subject, and it provides a space for the reader as we watch the characters struggle through this interaction. A different sort of pause comes at the end of the scene when Elinor does not know what to say and we glimpse her internal thoughts.

Dialogue should be used to create dynamic interactions between characters.

In dialogue, writers weave together the said, the unsaid, and action to create character interactions which should be dynamic, or in other words, should possess energy and life. This sort of dialogue is kinetic, in that it creates change and progress (though this be negative progress, moving the characters away from their goals).

Conflict and tension are created by dialogue when the character’s various wants and goals rub up against each other. Connection is created when the dialogue changes the characters’ relationship in a positive way. Ultimately, dialogue is communication, but it is also so much more: it moves the plot forward and provides characters with a way to manifest their personalities and move toward their goals.

Exercise 1: Take a book off your shelf and open it to a random page. Find the first sentence of dialogue on the page and use it as the first line of a conversation you write for brand new characters. Make sure to consider what the characters say, what the characters don’t say, and the actions of the characters.

(There is also a random dialogue generator online that can be used for this exercise.)

Exercise 2:

Write a short passage of dialogue (approximately 3-5 lines/paragraphs), featuring two characters, a girl who wants to buy a lollipop from a candy shop, and a guardian who is trying to save money and wants to get home and rest after a long day.

You will write this passage three different times:

For the first version of the dialogue, have both characters say exactly what they want.

For the second version of the dialogue, have one of the characters say exactly what they want, while the other character does not say what they want, but nevertheless tries to achieve what they want.

For the third version of the dialogue, neither character should say exactly what they want, yet both are trying to achieve their own goals.

In each version of the dialogue, consider how the character is speaking, and what actions they might take, as well as if any pauses would occur.

Exercise 3:

It’s easy to overwrite dialogue and include more than is necessary. Take a scene of dialogue that you have drafted and cut out at least 25% of the spoken sentences (you can cut out individual words too, but as you do so, make sure that you don’t lose your characters’ distinct voices).

#8: Use Setting to Influence Plot and Character

One of the most famous scenes from the book Emma occurs at Box Hill, a hill popular as a sightseeing attraction both in Jane Austen’s time and today. (Sadly, visiting Box Hill is an uncompleted item on my bucket list.)

A view from Box Hill by Benjamin Rusholme (Creative Commons license).

In this scene, Emma’s flaws are brought to the forefront: in an attempt to be clever and keep attention on herself, Emma is cruel to Miss Bates.

“Ladies and gentlemen—I am ordered by Miss Woodhouse to say…that she requires something very entertaining of each of you….[she] demands from each of you either one thing very clever…two things moderately clever[,] or three things very dull indeed, and she engages to laugh heartily at them all.”

“Oh, very well,” exclaimed Miss Bates, “then I need not be uneasy. ‘Three things very dull indeed.’ That will just do for me, you know. I shall be sure to say three dull things as soon as ever I open my mouth, shan’t I—(looking round with the most good-humoured dependence on everybody’s assent)—Do not you all think I shall?”

Emma could not resist.

“Ah! ma’am, but there may be difficulty. Pardon me—but you will be limited as to number—only three at once.”

Miss Bates, deceived by the mock ceremony of her manner, did not immediately catch her meaning; but, when it burst on her, it could not anger, though a slight brush showed that it could pain her.

“Ah!—well—to be sure. Yes, I see what she means, (turning to Mr. Knightley,) and I will try to hold my tongue. I must make myself very disagreeable, or she would not have said such a thing to an old friend.”

This scene’s effectiveness is dependent on its setting for two reasons:

- This setting has brought all of these characters together.

- The setting has created a set of trying circumstances for the characters.

In fiction, the setting of a scene should always be an intentional choice.

In Emma, many of the scenes do occur in Emma’s home, Hartfield. This is very deliberate: in many ways, Emma is trapped by having a hypochondriac as a father (the narrator calls him a “valetudinarian”). Yet there is still a large amount of variability in the settings, even if many of them happen at home or close to home. At seven miles away, Box Hill is the farthest Emma goes from home over the course of the novel, and this is a significant event for the characters, a day planned well in advance.

Setting influences plot. characters.

The choice of the setting should influence both the plot and the characters.

The narrator describes it as a “very fine day for Box Hill,” and everyone commences the seven-mile journey there in good spirits:

Seven miles were travelled in expectation of enjoyment, and every body had a burst of admiration on first arriving; but in the general amount of the day there was deficiency. There was a languor, a want of spirits, a want of union, which could not be got over.

Much of the tension of the scene is caused by contrast between the high expectations for Box Hill and the lack of enjoyment and feeling. Two hours are spent walking around the hill and seeing the sights, yet throughout the entire time, they are plagued by division and separation. In Emma’s opinion, people are behaving in a manner that is “dull” and “insufferable.”

Perhaps it is this struggle with the setting that brings Emma to an internal lowness that invites her to act in an outwardly low manner. (When I am tired, hungry, or overheated, I definitely lose some of my charming personality.)

After her rudeness, the group continues the conversation for a few more minutes but soon breaks apart:

Even Emma grew tired at last of flattery and merriment, and wished herself rather walking quietly about with any of the others, or sitting almost alone, and quite unattended to, in tranquil observation of the beautiful views beneath her.

Yet she does not have the opportunity to enjoy the beauty: in the next sentence, the carriages arrive. In a moment where they are alone, Mr. Knightley reproaches Emma for her behavior.

“How Could You Be So Unfeeling?” Knightley reproaches Emma in the 2020 film Emma. (Gif from Tenor.)

After this confrontation by Knightley, which once again occurs in stark contrast to the beautiful surroundings, Emma feels the full weight of guilt. The chapter ends with the following line:

Emma felt the tears running down her cheeks almost all the way home, without being at any trouble to check them, extraordinary as they were.

A well-chosen setting can have a huge influence on the plot and the characters, and the way in which the setting is described provides a lens into the viewpoint character’s thoughts and emotions.

Exercise 1:

Read the following dialogue, which will become part of a short break-up scene:

“I just don’t think it’s going to work out between us,” said Amisha.

“I’m not worried,” said Jesse. “We always get through things.”

“Yes, we could get through this,” said Amisha. “But that’s not what I want. I’m done. Done with this, done with us.”

Now choose two different settings and write two versions of this short scene (two to three paragraphs each). Make sure to not only add description, but also movement and action. Consider what they might be doing in the setting (i.e. cooking dinner in Amisha’s kitchen), how the characters would describe the setting, and how the setting will impact how both the characters and the reader.

Example settings:

- A kitchen

- The beach

- A freeway

- A museum

- A soccer game

Exercise 2:

Choose one of your favorite books or movies, and without rereading or rewatching it, make a list of as many settings as you can from the story. These can be broad settings (i.e. England, the town of Highbury, etc.) or more specific settings (i.e. Mr. Elton’s house, the strawberry patch, etc.).

Once your list is complete, consider the following question: How does the setting impact the plot and the characters in this story?

Exercise 3:

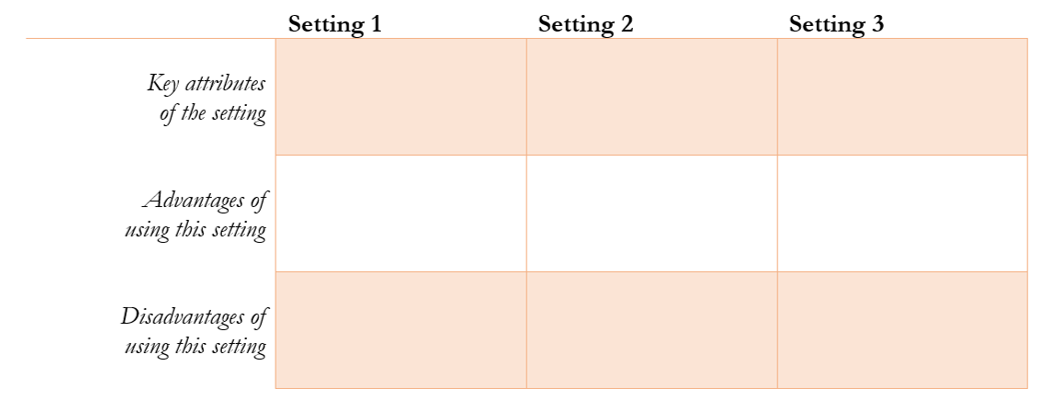

Option 1: Use a scene that you plan to write in a book or short story. Come up with three possible settings that could work well at fulfilling the purposes of the scene. For each setting, list the key attributes of the setting, the advantages of using the setting, and the disadvantages of using the setting.

Option 2: Take a scene that you have already written and rewrite it using a new setting. Which do you prefer? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each one?