#30: Introduce the Setting through Description

When I was in grad school, I studied Rhetoric and Composition (the teaching of writing). In a class I took which incorporated classical rhetoric, I wrote an essay about the Latin term descriptio, or what today we would call description. According to the website Silva Rhetoricae, description is “a composition bringing the subject clearly before the eyes.” In other words, it helps us visualize something on the page.

The Greeks and the Romans considered descriptio (description) to be the opposite of narratio (narrative).

Description≠Narrative

Narrative is about forward movement, it’s about story and progression, it’s about events happening. But anytime you have description, it halts the forward movement: we are now looking at something being painted before our eyes. And that painting takes time.

This is not to say that all description should be avoiding, but it is essential to realize as a writer that description competes with narrative.

Jane Austen, as always, is an excellent role model on how to use description, particularly in how she describes her settings. She gives enough detail to give us a sense and feel of the whole without disrupting the forward movement of the narrative.

In a previous post, I talked about the importance of using setting to influence plot and character. In this post, we’re going to look at a few passages from Elizabeth’s physical journeys in Pride and Prejudice to see how Jane Austen uses description to establish setting. In the process, I’ll talk about five specific techniques that she uses to powerfully introduce setting through description.

Technique 1: Provide a few key details which give a sense of the whole.

One of Austen’s primary techniques in establishing setting is to only use a few pertinent details. Unlike a production designer in a film, who must physically choose, create, acquire, and place every single item which we see, a novelist is generally best served by focusing on a few points that give a taste, a feel, or a sense of the whole.

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth’s first trip away from home is to visit her friend Charlotte Collins née Lucas. After Elizabeth turned downed Mr. Collins’ offer of marriage, her friend Charlotte accepted his hand, and now, at Charlotte’s behest, Elizabeth has come to visit the parsonage where they live.

In the following two passages from when Elizabeth arrives, note how we are given only a smattering of concrete descriptive details, yet from this we understand not just the setting, but the people who are part of it.

Passage 1 (emphasis added):

Elizabeth was prepared to see [Mr. Collins] in his glory; and she could not help fancying that in displaying the good proportion of the room, its aspect and its furniture, he addressed himself particularly to her, as if wishing to make her feel what she had lost in refusing him….After sitting long enough to admire every article of furniture in the room, from the sideboard to the fender…Mr. Collins invited them to take a stroll in the garden, which was large and well laid out, and to the cultivation of which he attended himself.

The sideboard and the fender stand in for all of the furniture, the rest of which we are meant to conjecture. For the garden we receive only two details: it is large and it is well laid out. More concrete particulars are not relevant.

Passage 2 (emphasis added):

Charlotte took her sister and friend [Elizabeth] over the house, extremely well pleased, probably, to have the opportunity of shewing it without her husband’s help. It was rather small, but well built and convenient; and everything was fitted up and arranged with a neatness and consistency of which Elizabeth gave Charlotte all the credit. When Mr. Collins could be forgotten, there was really a great air of comfort throughout, and by Charlotte’s evident enjoyment of it, Elizabeth supposed he must be often forgotten.

In this passage, Austen swiftly paints a picture of the house, giving not just concrete details, but also value judgments (neatness and consistency are a good thing, and reflect positively on Charlotte) and a more general, abstract sense of the feel (“a great air of comfort throughout”).

Technique 2: Use the description of the setting to reveal things about the characters and their states of mind.

On its most basic level, describing a setting is useful because it orients the reader—we feel grounded when we know where we are and what’s going on. Yet Austen never just uses setting description to orient us: she always makes it serve double-duty.

A good description reveals as much about characters and their states of mind as it reveals about the setting itself.

Mr. Collins’ parsonage abuts Rosings, the grand estate belong to his esteemed patroness, Lady Catherine de Bourgh.

They are invited to dinner, and they all walk together to approach Rosings. In the following description of setting, notice what is revealed about Elizabeth, and about Charlotte’s sister Maria and father Sir William:

Every park has it beauty and its prospects; and Elizabeth saw much to be pleased with, though she could not be in such raptures as Mr. Collins expected the scene to inspire, and was but slightly affected by his enumeration of the windows in front of the house, and his relation of what the glazing altogether had originally cost Sir Lewis De Bourgh.

When they ascended the steps to the hall, Maria’s alarm was every moment increasing, and even Sir William did not look perfectly calm.—Elizabeth’s courage did not fail her. She had heard nothing of Lady Catherine that spoke her awful from any extraordinary talents or miraculous virtue, and the mere stateliness of money and rank, she thought she could witness without trepidation.

It is clear that while Elizabeth sees the beauty and wealth of Rosings and its park, she does not let intimidate or overly influence her, unlike Mr. Collins (who expects raptures from them), Maria (who feels alarm as they go up what must be rather grand steps), and even Sir William (who should theoretically be the most comfortable with this level of wealth).

Technique 3: Couple the description of the setting with action within or in relation to the setting.

While description can at times slow or halt the plot, at times they can be paired together. Rather than completely describing a setting and then having action occur within it in, Jane Austen will provide details of the setting as an action occurs.

As Elizabeth encounters Rosings, they are moving, both physically and emotionally, to meet the great Lady Catherine; Mr. Collins is talking—describing the place (speech in itself is a type of action); and we are learning more about the setting and its inhabitants as we physically pass through it:

From the entrance hall, of which Mr. Collins pointed out, with a rapturous air, the fine proportion and finished ornaments, they followed the servants through an antechamber, to the room where Lady Catherine, her daughter, and Mrs. Jenkinson were sitting.

A few pages later, Austen uses the same technique, describing other objects in the space as they are used.

When the gentlemen had joined them, and tea was over, the card tables were placed. Lady Catherine, Sir William, and Mr. and Mrs. Collins sat down to quadrille; and as Miss De Bourgh chose to play at cassino, the two girls had the honour of assisting Mrs. Jenkinson to make up her party.

Technique 4: Use minimal description of the setting (or omit it entirely) when the setting is not necessary to the story.

It is the temptation of the writer to describe, in full detail, cool places, buildings, and objects, even when doing so is not absolutely necessary to the story. This is an indulgence which Austen tends to avoid. (Some writing styles like to linger on setting for setting’s sake, and doing so can also be effective, but even if you are writing in one of these styles, there is still a risk of over-indulging in description.)

Later in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth takes a trip with her aunt and uncle to Derbyshire, which happens to be where Mr. Darcy lives. Despite this being a sight-seeing trip for Elizabeth, full of interesting towns, landscapes, and historic sights which could easily be a full chapter, and could possibly reveal something about Elizabeth’s character or her relationship with her aunt and uncle, Austen does not provide any description of the setting, and her narrator even comments on the fact that she is not providing description:

It is not the object of this work to give a description of Derbyshire, nor of any of the remarkable places through which their route thither lay; Oxford, Blenheim, Warwick, Kenelworth, Birmingham, &c are sufficiently known. A small part of Derbyshire is all the present concern.

The small part of Derbyshire the narrator focuses on is Lambton, which Mrs. Gardiner has a personal connection to, and which happens to be near Mr. Darcy’s home, Pemberley.

Technique 5: Give more detailed setting descriptions when the setting can strengthen a key component of the narrative.

While at many points in a story description is unnecessary, or is useful only in small portions, at other times detailed description of a setting can add depth to a story, highlight a character’s deep emotions or internal transformation, and prepare the reader for what is to come.

In contrast to the minimal description of the parsonage and Rosings, and the complete lack of description of the rest of the “remarkable places” during the journey to Lambton, Austen provides pages of description about the grounds and interior of Pemberley. Here are the first few paragraphs:

Elizabeth, as they drove along, watched for the first appearance of Pemberley Woods with some perturbation; and when at length they turned in at the lodge, her spirits were in a high flutter.

The park was very large, and contained great variety of ground. They entered it in one of its lowest points, and drove for some time through a beautiful wood, stretching over a wide extent.

Elizabeth’s mind was too full for conversation, but she saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view. They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. It was a large, handsome, stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills;—and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt, that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!

This level of description is more powerful for having been saved for this moment. Elizabeth’s level of engagement with the setting, as demonstrated by the copious description, shows her attentiveness not just to Pemberley but to its owner, Mr. Darcy. Elizabeth is not just noticing a setting: she is interacting and engaging with it, and it is as she does so that she has the first conscious realization that maybe she should have accepted Mr. Darcy’s proposal.

Exercise 1: Choose one of your favorite authors and examine how they use description to establish setting. What techniques do they use? Are they the same as those used by Jane or are they different? What is the effect of the setting description on the story?

Exercise 2: Write a short scene involving three people walking through a graveyard. Include details about the setting, but do so in a way that reveals things about all three characters and their states of mind.

Exercise 3: Take a story that you have drafted and find places that include (or could include) setting description. Find the following in your manuscript:

- A passage where you could reduce or eliminate description.

- A passage where you could use different details that might give a better overall sense of the setting.

- A passage where setting could be revealed through action.

- A place where the description of the setting could reveal more about the characters and their state of mind.

- A key scene in which more description of the setting could be added to increase the impact of the scene.

Now consider if any of these changes would both match your vision and improve your story; if so, revise!

#29: Use Antagonists as Character Foils

There’s a rather brilliant musical adaptation of Emma that I saw performed live in Chicago (in February 2020, right before everything shut down!).

In one of the songs, “The Recital,” Emma plays the pianoforte and sings at a gathering (while also feeling a little jealous of the attention that Mr. Knightley is paying to Jane Fairfax). And then, Jane moves to the pianoforte and begins to play at about the 1 minute 15 second mark—her playing and singing are clearly superior to Emma’s.

“She plays well, does she not?” says Mr. Knightley.

“Only if you enjoy that polished, extremely gifted sort of talent,” replies Emma.

(You can listen to the song on YouTube—stop at about 2 minutes 39 seconds in, because then it transitions to Harriet’s musings.)

What I love about Paul Gordon’s song is that it brilliantly establishes a contrast between Emma and Jane Fairfax, which is made very directly by having them play the very same song. (To me, this works really well for the musical genre.) It’s a shorthand to establish Jane Fairfax as Emma’s foil.

What is a Character Foil?

A character foil is a character who is set up in direct contrast to another character; their opposing attributes or circumstances are featured, with the purpose of revealing things about character and story.

Having a number of different characteristics is not enough for characters to be foils: all characters should be distinctive in some way, and dozens of characters in the story will have contrasting attributes.

In order to be true foils the characters must have something substantial in common, which both invites comparison between the characters and makes their differences more apparent.

Emma and Jane Fairfax are foils to each other. Not only is Jane Fairfax “exactly Emma’s age,” but they are two of the only gentlemen’s daughters in Highbury, and they both have many accomplishments. Yet Jane Fairfax is actually more accomplished; she applies herself with dedication to things while Emma does not. And Emma is in a position of power, wealth, and security, while Jane has none of these things.

A Foil as Antagonist

Not all character foils are antagonists, but many times they are: two people with conflicting characteristics or approaches to life can make natural antagonists. Tension and conflict easily arise between these characters, and it can be a powerful storytelling technique which raises the stakes, highlights the different sorts of choices that could be made (along with resulting consequences), and sheds light on character motivations.

Whether or not a character foil also serves as an antagonist, important contrasts are demonstrated.

A character foil can serve to demonstrate contrast:

- To the protagonist

- To other characters in the novel

- To the reader

In many novels, the foil demonstrates contrast to one or two of these groups, but in Jane Austen’s Emma, contrasts are demonstrated for all three groups.

Contrast demonstrated to the protagonist:

In the opening line of Emma, we learn that Emma is “handsome, clever, and rich,” and throughout her life she has “very little to distress or vex her.”

Yet the existence and presence of Jane Fairfax does vex Emma. When Jane returns to Highbury to stay with her relatives, this is Emma’s internal reaction:

Emma was sorry;—to have to pay civilities to a person she did not like through three long months!—to be always doing more than she wished, and less than she ought! Why she did not like Jane Fairfax might be a difficult question to answer; Mr. Knightley had once told her it was because she saw in her the really accomplished young woman, which she wanted to be thought herself; and though the accusation had been eagerly refuted at the time, there were moments of self-examination in which her conscience could not quite acquit her. But “she could never get acquainted with her: she did not know how it was, but there was such coldness and reserve—such apparent indifference whether she pleased or not—and then, her aunt was such an eternal talker!—and she was made such a fuss with by every body!—and it had been always imagined that they were to be so intimate—because their ages were the same, every body had supposed they must be so fond of each other.” These were her reasons—she had no better.

Emma knows they are the same age, she knows they should have been friends—she is aware of their similarities, and she constantly attempts to emphasize their differences:

She was, besides, which was the worst of all, so cold, so cautious! There was no getting at her real opinion. Wrapt up in a cloak of politeness, she seemed determined to hazard nothing. She was disgustingly, was suspiciously reserved.

Throughout the story, Jane Fairfax also reveals things to Emma about herself: Emma finds herself worried, and perhaps even jealous, when there seems to be a romantic interest between Mr. Knightley and Jane Fairfax.

Contrast demonstrated to other characters in the novel:

The first time in the novel that Jane Fairfax is referenced is actually by Harriet Smith, in conversation with Emma:

“Do you know Miss Bates’s niece? That is, I know you must have seen her a hundred times—but are you acquainted?”

“Oh! yes; we are always forced to be acquainted whenever she comes to Highbury. By the bye, that is almost enough to put one out of conceit with a niece. Heaven forbid! at least, that I should ever bore people half so much about all the Knightleys together, as she does about Jane Fairfax. One is sick of the very name of Jane Fairfax. Every letter from her is read forty times over; her compliments to all friends go round and round again; and if she does but send her aunt the pattern of a stomacher, or knit a pair of garters for her grandmother, one hears of nothing else for a month. I wish Jane Fairfax very well; but she tires me to death.”

Emma’s verbal treatment of Jane Fairfax should act as a warning to Harriet: Emma is not perfect, her vision can be skewed, her intentions not always kind or correct. But despite seeing Jane Fairfax and Emma placed side by side, Harriet does not notice or heed this warning, and it allows Emma to inflict a fair amount of emotional damage on Harriet.

Other characters see a contrast between Emma and Jane Fairfax and chose sides. It is clear, for instance, that Mrs. Elton does not particularly like Emma. She does take a liking to Jane Fairfax and attempts to take her under her wing. Yet Mrs. Elton’s attentions are not always good for Jane Fairfax, something which Emma feels (and even begins to disagree with) as she watches Mrs. Elton attempt to take away Jane’s limited autonomy.

Contrast demonstrated to the reader:

Even before Jane Fairfax is introduced, it is clear that Emma is not always the best person—she can be unlikeable, interfering, and a bit of an antihero. Setting up a foil for Emma further highlights her failings, negative qualities, and weaknesses.

The foil also helps create a beautiful redemption arc for Emma, because it takes a long time, but Emma does begin to change and improve. Despite their differences and her long-proclaimed dislike of Jane Fairfax, Emma realizes and resolves:

“I ought to have been more her friend.—She will never like me now. I have neglected her too long. But I will shew her greater attention than I have done.”

It is not long before Emma is put to the test. She almost uses her wit against Jane Fairfax, as she is wont to do:

She could have made an inquiry or two, as to the expedition and the expense of the Irish mails;—it was at her tongue’s end—but she abstained. She was quite determined not to utter a word that should hurt Jane Fairfax’s feelings; and they followed the other ladies out of the room, arm in arm, with an appearance of good-will highly becoming to the beauty and grace of each.

Later, Jane is feeling unwell and decides to leave a social event at Donwell Abbey early. At first, Emma tries to do what she thinks would be the most kind and solicitous action—to call a carriage. But ultimately, she allows Jane Fairfax to do what Jane wants, which gives her the autonomy and societal power she is often denied. The following passage begins with Jane speaking:

“I am fatigued; but it is not the sort of fatigue—quick walking will refresh me.—Miss Woodhouse, we all know at times what it is to be wearied in spirits. Mine, I confess, are exhausted. The greatest kindness you can shew me, will be to let me have my own way, and only say that I am gone when it is necessary.”

Emma had not another word to oppose. She saw it all; and entering into her feelings, promoted her quitting the house immediately, and watched her safely off with the zeal of a friend. Her parting look was grateful—and her parting words, “Oh! Miss Woodhouse, the comfort of being sometimes alone!”—seemed to burst from an overcharged heart, and to describe somewhat of the continual endurance to be practised by her, even towards some of those who loved her best.

The contrast between the characters and their evolving relationship creates a powerful story for readers. While Emma and Jane Fairfax never have a complete, total reconciliation, the transformation of their relationship is dramatic.

Wrapping up

Not all character foils need to have this sort of reconciliation. And sometimes, a character foil is used for a character other than the main protagonist. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy and Mr. Wickham acts as foils to each other, and while a sort of agreement is reached between them at the end of the novel, it is more of a triumph of Darcy and his principles over Wickham.

Using character foils can be a powerful tool, especially with antagonists, which can create marked contrasts for the protagonist, for other characters, and for the reader.

Exercise 1: Think about one of your favorite character foils from a book or a movie. What do the characters have in common? What is different about these characters? Who notices this contrast, how does this foil effect the plot, and what is the impact of this foil on the reader?

Exercise 2: Take one of your characters who does not have a foil (either from a story you have already written or a character you have brainstormed). Craft a character who could be an effective foil for this character. What would be the advantages of using a foil in your story? What would be the disadvantages?

Exercise 3: Choose a classic fairy tale character, like Belle from Beauty and the Beast. Now create a character foil for this character. The catch: you have to use this random number generator.

Use the random number generator 3 times to choose 3 of the following possible contrasts. Use these three types of contrasts to craft a character foil for the fairy tale character (but also make sure to give the characters enough in common that they are set up as foils).

General categories of possible contrasts:

- Background

- Education

- Personality

- Choices

- Approach to life

- Physical attributes or abilities

- Mental attributes or abilities

- Economic status

- Power/hierarchy

- Gender

- Passive/active

- Strengths/weaknesses

- Wants/needs

- Sympathetic/unsympathetic

Bonus: do the same exercise, but this time use the generated numbers to choose the things that are similar about the characters.

#28: Give Antagonists Redemptive Qualities

I spend a lot of time playing with dolls with my 5-year-old daughter. She likes to divide them up and make half of the dolls “good guys” and half of the dolls “bad guys.” The bad guys really like kidnapping other dolls and taking over the ice castle.

Sometimes when she assigns me the bad guys, I try to act out things like them sharing food with each other, or playing a game together.

“No, Mom!” she will exclaim. “They are bad guys. They can’t do anything good.”

In general, I’m really impressed by my daughter’s storytelling skills—I may be biased, but I feel like they are advanced for a 5-year-old—but I partially disagree with her on this one. It’s true that there are some antagonists who don’t do anything good, and there are some villains who are true and complete loners, but for the most part, antagonists often have some good or redemptive qualities. At the very least, there are reasons that other people support them and spend time with them.

John Willoughby is one of my all-time favorite antagonists from Austen. He’s the classic bad boy character, and in the novel Sense and Sensibility he doesn’t end up redeeming himself by giving Marianne the initial happy ending that she initially sought. Yet Austen still gives him some element of redemption.

Initial Good/Redemptive Qualities

John Willoughby is introduced through an act that screenwriter Blake Snyder would call a “save the cat” moment—Willoughby does something selfless and good that immediately endears him to us and to the characters. Marianne has fallen down a hill, and he lifts her and carries her home.

Score one for Willoughby.

As the story progresses, he demonstrates a number of good qualities, all of which Marianne prizes highly:

- Giving his time

- Generous with means (offering a horse to Marianne)

- Handsome

- Reading poetry and literature with Marianne

- Friendly and gets along well with almost everyone

And the Antagonism

While Elinor never quite trusts Willoughby, and finds some of these very behaviors problematic (it’s not really appropriate for Willoughby to give Marianne a horse, plus what would they do with it?) his antagonism quickly becomes clear to everyone.

He:

- Doesn’t actually solidify or finalize an engagement with Marianne

- Leaves and doesn’t return, and when Marianne goes to London, he avoids her and does not return her letter (or, as we would now say, he ghosts her)

Definition of “ghost” from Merriam-Webster dictionary.

- It turns out that he has previously gotten a teenage girl pregnant

- He marries another woman for financial reasons.

His Motives for Antagonistic Behavior

In the last two lessons I talked about different motives that Jane Austen gives her antagonists in Sense and Sensibility—selfish motives, negative motives, positive motives, and mixed or neutral motives. Having understandable motives, whether or not they are ones we support, give a character depth and reality. Willoughby possesses each of these types of motives:

- Selfish motives: Sleeping with an easily influenced teenage girl

- Negative motives: Disregarding propriety and societal expectations, playing with Marianne’s affections

- Positive motives: helping Marianne when she has fallen, realizing that he has genuine interest in her and trying to find a way to make a relationship possible

- Neutral motive: seeking financial stability/security: (in and of itself, the need for financial security is not a negative thing; it’s much more complex than that—many of Austen’s characters grapple with this, including Marianne and Elinor Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, and, in her other novels, the Bennet sisters, Charlotte Collins, Anne Elliot, Jane Fairfax, and Fanny Price.)

Letting Willoughby Tell His Story

I took a graduate-level class on Jane Austen, and we spent a fair amount of time discussing a particular Willoughby scene that is not included in a number of adaptations.

This scene occurs when Marianne is extremely ill, due to a combination of heartbreak and spending too long in the cold and the rain (deathly illness due to these causes seems to be an occupational hazard of being a young woman in the Regency period).

Willoughby comes in the middle of the night and insists on speaking to Elinor. To his credit, he is extremely worried about Marianne’s health, and is grateful she has taken a turn for the better. At first, Elinor thinks that he must be intoxicated, but he is not, and he insists on Elinor listening to him, which she is not inclined to do:

“Mr. Willoughby, you ought to feel, and I certainly do—that after what has passed—your coming here in this manner, and forcing yourself upon my notices, requires a very particular excuse.—What is it, that you mean by it?”—

“I mean,”—said he, with serious energy—“if I can, to make you hate me one degree less than you do now. I mean to offer some kind of explanation, some kind of apology, for the past; to open my whole heart to you, and by convincing you, that though I have always been a blockhead, I have not been always a rascal, to obtain something like forgiveness from Ma—from your sister.”

Jane Austen then gives Willoughby page after page after page to explain himself. He admits all his terrible motives, including:

“Careless of her happiness, thinking only of my own amusement, giving way to feelings which I had always been too much in the habit of indulging, I endeavoured, by every means in my power, to make myself pleasing to her, without any design of returning her affection.”

We see his angst, his attempts to justify himself, his pride and selfishness, his arguments good and bad. And we see glimpses of redemption:

“The happiest hours of my life were what I spent with her, when I felt my intentions were strictly honorable, and my feelings blameless.”

Ultimately, Elinor comes to understand him a little, and to truly understand a person is a token of forgiveness, a gift of humanity for them and for the reader:

[Elinor’s] thoughts were silently fixed on the irreparable injury which too early an independence and its consequent habits of idleness, dissipation, and luxury, had made in the mind, the character, the happiness, of a man who, to every advantage of person and talents, united a disposition naturally open and honest, and a feeling, affectionate temper. The world had made him extravagant and vain—Extravagance and vanity had made him cold-hearted and selfish. Vanity, while seeking its own guilty triumph at the expense of another, had involved him in a real attachment, which extravagance, or at least its offspring, necessity, had required to be sacrificed. Each faulty propensity in leading him to evil, had led him likewise to punishment.

Ultimately, Elinor expresses her forgiveness to Willoughby. It’s a fascinating scene, worth reading its entirety. In general, Jane Austen’s antagonists are some of her most memorable characters, because they are full of depth, complexity, and nuance. Often we come to understand their motives and character quite well, but here, Austen gives him a gift not often given to antagonists: he is able to fully tell his own story. Unless the antagonist is a viewpoint character, it’s very uncommon for an antagonist to receive this opportunity. The ability for Willoughby to admit his faults doesn’t make his choices better. But it does force us as readers to truly walk in Willoughby’s shoes, which enhances the themes and tensions of the novel.

Redemptive Qualities

While most of the time an antagonist won’t have a chance to fully tell their story, in many cases we get a glimpse of their story. Their motives—positive, negative, and neutral—should be understandable, even if we don’t always agree with them. And at times, an antagonist should possess some redemptive qualities (for instance, in Pride and Prejudice, Lady Catherine de Bourgh is good and generous to Mr. Collins). This helps make the antagonists complex, nuanced, and memorable.

Exercise 1:

Take an antagonist that you have written into a story or plan to write. Give them the opportunity to explain themselves, whether through the form of internal monologue, a journal entry, a letter to a close friend, or a conversation.

Exercise 2:

Write a short personal essay about a time in your own life when you’ve had a chance to explain yourself and your behavior, or when you wish that you had gotten a chance to explain yourself.

Exercise 3:

Take a book, movie, or series that you know well and list at least five antagonists or villains present in the story. Then write down as many redemptive qualities as you can for each of these characters.

#27: Give Antagonists Understandable Motives (Part 2)

Jane Austen’s antagonists are some of her most memorable characters—full of depth, complexity, and nuance, and continuously getting in the way of protagonists.

In the last lesson, Give Antagonists Understandable Motives (Part 1), I addressed negative motives for antagonism, like selfishness, a disregard for social norms, spite, cruelty, and revenge.

Yet not every antagonist interferes with the protagonist for negative reasons. Plenty of antagonists have positive or neutral motives for their interference. And these sorts of motives will be the focus of this lesson.

Positive Motives for Antagonism

Sometimes good people, trying to do good things, unintentionally make life more difficult for others.

Positive motives can be antagonistic when:

In Sense and Sensibility, there are a number of people who attempt to do good for the Dashwood family, yet are sometimes unintentionally antagonistic.

Sir John Middleton has offered his cottage to the Dashwoods because of their lack of their home, which is very generous of him, but also creates a lot of obligation for Mrs. Dashwood, Marianne, and Elinor.

Marianne especially finds Sir John antagonistic toward her goals, as well his wife, Lady Middleton, and her mother Mrs. Jennings and sister Mrs. Palmer. They are constantly interfering with Marianne’s sense of self, her need for independence and solitude, and her desires for certain types of company. They also are trying to matchmake a relationship between Marianne and Colonel Brandon, and they do this out of good motives—they seem like they would make a good match, and it would give Marianne a very advantageous marriage and help her out of poverty. But that’s not what Marianne wants.

Elinor finds the Middletons less antagonistic than Marianne does, yet sometimes their teasing and their mannerisms do make her uncomfortable and act in opposition to her journey.

Another example of an antagonistic character in Sense and Sensibility is Mrs. Dashwood herself. At the beginning of the novel, she does not want to economize, which makes finding their family a home very difficult. She also overprioritizes her love for Marianne, to the point where she refuses to act as a parent figure and talk to Marianne about the pitfalls of her behavior. She’s so afraid with damaging their relationship that she won’t even ask Marianne if she is engaged, and rather than helping Marianne, this contributes to Marianne’s difficulties (and also to Elinor’s). To me, she is one of the most interesting characters, because she is likeable and good and yet so very flawed in her behavior.

Neutral Motives for Antagonism

While a lot of antagonistic motives are clearly either negative or positive, some motives are more neutral.

A few types of neutral motives that can be antagonistic:

A sometimes-antagonistic character who has neutral motives is Edward Ferrars. Elinor falls in love with Edward, and while at Norwood Park he seems to return her affections. But when Elinor, her sisters, and her mother move, he becomes entirely absent from her life, which causes a lot of angst and sadness for Elinor. He eventually visits, but the visit is a rather uncomfortable one.

It turns out that several years before Edward became secretly engaged to Lucy Steele. Because he is a man of his word and trying to do the right thing, he won’t break off his engagement to Lucy, because that would hurt her and break his word. Yet in being honorable to Lucy, he is breaking Elinor’s heart, and giving his attentions to Elinor in the first place wasn’t very fair, knowing that he did not intend to act.

Neutral motives that create antagonism are some of the most interesting to explore in literature because they cause so much tension and they allow writers to explore the nuances and complexities of relationship and morality.

In Conclusion

Story is about conflict, it’s about a character on a journey interrupted, a journey that has challenges, many of them caused by other characters. As a protagonist goes about their journey, they face antagonism not just from Antagonists—people that are actively and intentionally opposing the core journey—but also from characters, large and small, who might be friends, family members, or acquaintances. Considering the full range of motives for antagonism can help you write more complex and interesting stories.

Next lesson we’ll focus on one final antagonist in Sense and Sensibility, my favorite Jane Austen bad-guy, John Willoughby. He has positive motives, he has negative motives, and he has neutral motives. Ultimately Jane Austen treats him with a certain kindness, allowing him some level of redemption, by giving him a chance to tell his story.

Exercise 1:

Think about someone in your life—currently, or in the past—who has good motives, and yet makes your life more difficult or negatively interferes in certain areas of your life. Write several paragraphs about this person and their behavior. Make sure to examine specific actions they take (whether physical actions, dialogue, text, etc.) that act antagonistically in your life, and record also your reaction to these actions in the moment and over time.

Exercise 2:

Write several paragraphs from the viewpoint of an antagonist who is forced to choose between two competing principles:

- Telling the truth; being sensitive to the feelings of others

- Being on time; being prepared

- Helping someone else; taking care of your own basic needs

- Saving for the future; enjoying the moment

- Another pair of competing principles you create

After they make the choice between the principles, have the character experience both positive and negative consequences as a result of their choice.

Exercise 3: A No Good, Very Bad Day

Set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes and do a rush write about a character, in which everything they do over the course of the day has negative or unforeseen consequences for other people.

#26: Give Antagonists Understandable Motives (Part 1)

As I discussed in the previous post, an antagonist is a person who actively opposes the main character and tries to interfere with them achieving their wants and needs, typically over multiple scenes or a large portion of the story.

One of the things that makes Jane Austen’s protagonists so effective is that they always have understandable motives. As readers, we don’t always know these motives immediately, but ultimately these motives are explainable and understandable.

We’re going to consider four different categories of antagonist’s motives, with examples from Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility. In today’s post, Part 1, we’ll look at more negative types of antagonism, and in the next blog post, Part 2, we’ll consider more positive or neutral types of antagonism.

Self-Interested Motives

The first major category of motives held by antagonists is self-interest.

All characters, antagonists and protagonists, act with a certain amount of self-interest. It’s the only way, as people, we can survive—it’s the only way we get our wants and desires. And we often support characters striving for their wants and needs, and we become frustrated with characters like Fanny Price in Mansfield Park when they don’t actively strive for their wants and needs.

Self-interest becomes antagonism when:

- A character’s self-interest interrupts the protagonist’s journey.

- A character’s self-interest harms other characters, or is done with a regard only for oneself.

In the second category of self-interest as antagonism, we often see:

Ultimately, self-interest is a prioritization of ones own needs and wants over the needs and wants of others.

An example of an antagonistic character acting with self-interest from is found in Fanny Dashwood (of Sense and Sensibility). Fanny does not want to see any of her husband’s inheritance go to his half-sisters or stepmother.

“It was my father’s last request to me,” replied her husband, “that I should assist his widow and daughters.”

“He did not know what he was talking of, I dare say; ten to one but he was light-headed at the time. Had he been in his right senses, he could not have thought of such a thing as begging you to give away half your fortune from your own child.”

Slowly Fanny works her husband down, appealing to their sons supposed needs and other self-focused arguments, until ultimately her husband decides not to give them any money, and only occasionally assist them with minor things:

“Your father thought only of them. And I must say this: that you owe no particular gratitude to him, nor attention to his wishes; for we very well know that if he could, he would have left almost everything in the world to them.”

This argument was irresistible. It gave to his intentions whatever of decision was wanting before; and he finally resolved, that it would be absolutely unnecessary, if not highly indecorous, to do more for the widow and children of his father, than such kind of neighbourly acts as his own wife pointed out.

Another character who acts with self-interest is Lucy Steele. She has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for four years, and now he is in love with Elinor Dashwood. It’s quite understandable that she would act in her own self-interest and attempt to maintain her engagement. She obviously has (or at least, had) feelings for Edward, and this is her chance for a better life. She is a dislikeable character because of the things she does in the name of self-interest, but we’ll talk about that more in the next section.

Outward-Focused Negative Motives

The second major category of antagonist motives are those which are outwardly-negative.

There are a number of these outward-focused negative motives, including:

All of these motives are manifestations of natural human emotions and inclinations. All people feel them, and most of us have acted with them to some degree or another.

Some characters are fixed in these sorts of motives, embracing them; other resist these motives, or turn to them in moments of extreme pressure, struggle, or pain.

In Sense and Sensibility, Mrs. Ferrars is generally cruel, controlling, and unpleasant to those around her. When Edward and Lucy’s secret engagement is revealed, she lashes out. In an act of anger and revenge, she disinherits Edward.

(As an interesting note, some scholars and other readers have noted that Mrs. Ferrars and Fanny Dashwood are both characters of power who are using and maintaining power in a society where traditionally women don’t hold any power. Even though I still find them to be unlikeable characters, this perspective helps me understand, and in some ways sympathize, with their motives.)

Sometimes acting on negative motives happens in the moment. At other times, as in the case of Lucy Steele, it’s planned and premeditated.

Lucy realizes that Edward has fallen in love with Elinor, so she is intentionally manipulative. She “confides” her troubles about her secret engagement to Elinor, after extracting a promise that she will not tell a soul. And then she continues to be intentionally cruel and manipulative, manifesting a fair amount of spite towards Elinor.

In Conclusion

These negative motives for antagonism are very common in literature: even in Sense and Sensibility, there are numerous examples. In a sense, they are an answer to the question—what happens if we stop following societal rules and expectations for “good behavior”? This makes for good storytelling, because it creates the opportunity for conflict.

In the next lesson, we’ll focus on positive (as well as neutral and mixed) motives for antagonism.

Exercise 1: Negative Perspectives

Some stories explore the perspective of a character fueled by negative motives. For example, in The Count of Monte Cristo, we see someone driven by revenge. And in the story of Robin Hood, a transgression of societal rules and laws (continuous theft of money and property) is shown to be justified as we see his reasons and what he does with this wealth (gives it to the poor).

Other stories, like The Wizard of Oz, give understandable motives to the villains, but still do not allow us to sympathize with them (the wicked witch is understandably angry at Dorothy for killing her sister, yet we are ). Some stories, like Wicked, explore more fully the seemingly negative motives of antagonists—here, the “wicked” witch is not truly wicked, despite some of her negative motives and choices.

Choose a story that does not explain or develop the antagonist’s motives, and write a paragraph or two exploring what their motives might be.

Exercise 2: Good Actions, Negative Motives

Many times, we assume that good actions must have positive motives behind them. Yet good actions can just as well be driven by negative motives. Good actions can be driven by self-interest, or by outward-facing negative emotions, like jealousy, revenge, or a desire to control others.

Set a timer for 3 to 5 minutes. During the time, come up with a negative motive that could drive each of the following actions. If you have time, write extra details about how this motive would play out during the scene.

- Donating to a charity/volunteering at a food bank

- Throwing a large party and inviting the whole neighborhood

- Revitalizing a city’s downtown

- Running for the school board

- Creating a new work of art

Exercise 3: Protagonists with Negative Motives

Antagonists with negative motives are interesting, but sometimes, protagonists with negative motives can be even more interesting.

Option 1: Brainstorm a protagonist that is sometimes driven by negative motives. In what sorts of circumstances do they act on these negative motives? When do they resist these negative motives? What are positive and negative effects of theme acting on these negative motives?

Option 2: Analyze a draft that you have written. At what points is your character driven by negative motives? Is there a point where it would be useful to give the character a negative motive?

2020 In Review, and Writing like Alexander Hamilton

The time has come—the long-awaited time of year in which I interrupt your life with charts, beautiful charts!

It’s year in review time. And despite the trash fire that 2020 has been overall, it’s been a really good writing year for me.

(Now I do feel a little self-conscious about it having been a good writing year. So many people have struggled with so much this year—loss of loved ones, personal health, jobs, etc. And as a result of those things or just general 2020ness, many people who have wanted to write have found themselves unable to write. I have a friend who has dozens of published books, and she has not been able to write much this year at all. If this is what your year was like, don’t need to beat yourself up for it. There are times and seasons for everything, and if you weren’t able to write or progress towards your personal goals this year, there will be years where you can.)

And now, on to my charts.

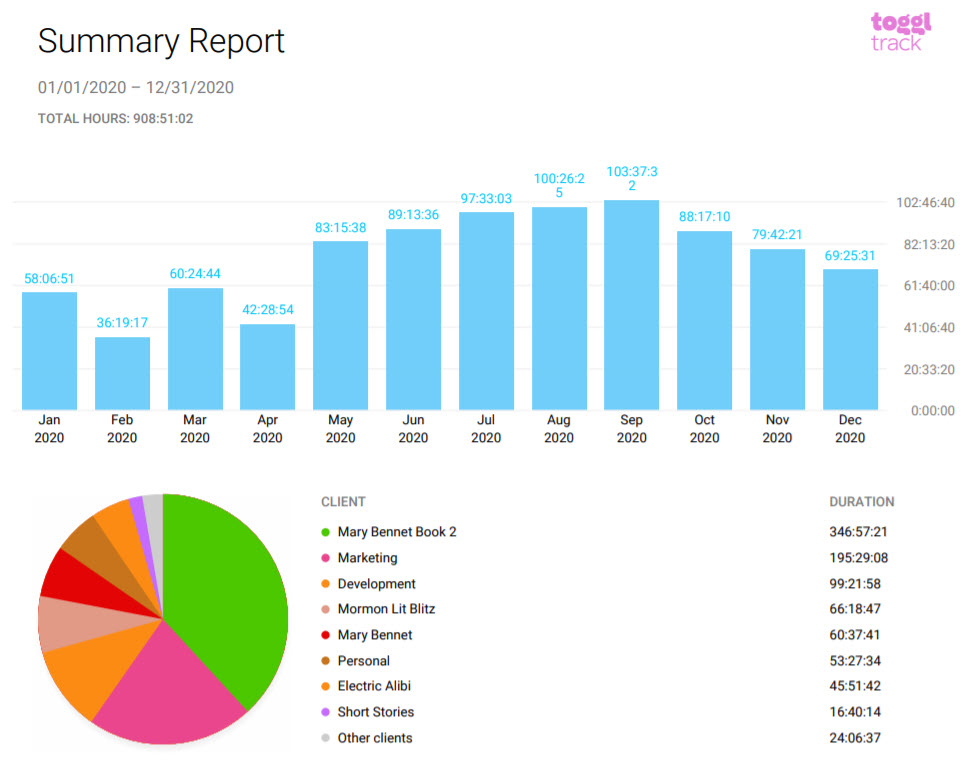

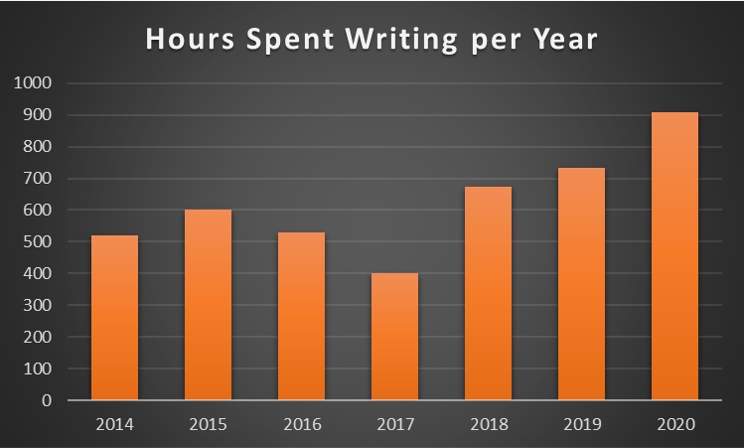

This Year I Wrote for 909 Hours

Note: by “writing” I include research, outlining, revision, planning, writing group, critiquing, listening to writing podcasts, writing accounting, etc…. For example, the “marketing” category includes a multitude of things, including my website (which I revamped this year), blog posts, writing-related social media posts, and conferences and library presentations (I gave two presentations this year). Development includes critiquing, writing group, networking, listening to writing podcasts, and reading books about writing craft.

909 hours works out to an average of 2.5 hours every single day including weekends (if you only include weekdays, it would be an average of 3.5 hours per day). So basically, it was my part-time job.

This is by far the most I have ever written in a year. As evidence, I present another chart:

The bulk of my time this year was spent working on my Mary Bennet series. (Which relates to my biggest writing news of the year—I got a three-book-deal with Tule!)

This year I spent 60 hours on the first Mary Bennet book (revisions and copy edits for Tule), 347 hours on the second Mary Bennet book (starting with the second draft, and revising it until it was ready to submit to Tule), and 9 hours on the third Mary Bennet book (this is the one I wish I had spent more on, because I really need to make progress on book 3).

Here’s the cover of the first book, which will be out on April 22nd, 2021:

(If you use Goodreads and haven’t yet added the book to your shelves, here’s the link!)

Another task that I put a lot of hours into was my Jane Austen Writing Lessons. I spent 125 hours on them, and I feel like the posts are really useful in terms of writing craft (and writing them has been a great diversion for me—it’s refreshing to write something that’s more essay-ish rather than fiction). Interesting note—of the 94,500 new words I wrote this year, 36,500 words were on Jane Austen Writing Lessons. So I’ve basically blogged half of a nonfiction book, which is pretty cool, to be honest.

How in the World Did I Write 909 hours during a Global Pandemic?

In part, this was due to the fact that I sort of lost my job this year.

I wasn’t fired. But due to university budget constraints, I wasn’t assigned a section to teach this fall, so I’m not working, and I’m not getting paid. Because I wasn’t actually fired, I can still access the university library (including the Oxford English Dictionary online) and keep my subscription to the New York Times.

Not working has had the side effect of giving me extra hours to write.

Also, the lack of going places and doing things this year has given me extra hours. For instance, I typically write a lot less in the summer, due to driving my kids to lessons and activities, as well doing a bit of travel. Suddenly, this summer, I had a lot more time, and my kids have now hit an age where they were better at entertaining themselves and each other.

Yet the biggest reason I’ve managed to write so much is that I’ve been channeling Alexander Hamilton (or at least the Lin-Manuel Miranda version of him)

Two of my favorite lines from Hamilton are in the song “Non-Stop”:

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

How do you write like you need it to survive?

Why do you write like you’re running out of time?

This year, I’ve felt like I’m running out of time. And I accept full responsibility for this. When my agent started pitching The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet to publishers at the beginning of the year, I already had written a first draft of the second book in the series. So I was confident that if the series was picked up by a publisher, I could revise book 2 this year.

Lo and behold, Tule acquired the entire trilogy, and in my contract listed the date by which I would submit book 2 to them. November 1st, 2020. This was the date I provided, but it ended up being a challenging date to reach.

The book needed a lot more work than I realized—it was a hard book to write, a hard year for me to resolve story problems and actually get words onto the page, and so I spent the entire year writing and revising like I was running out of time. But I made the deadline, and I’m really happy with the results!

(The thing is, I would probably set a similar deadline for myself if I was writing a new trilogy. I would just keep my fingers crossed that there wouldn’t be a global pandemic during the process of writing.)

Why do you write like you need it to survive?

Writing has been one of the things that give me joy, that makes me feel steady and centered, and that gives me purpose and direction. And it truly helped me get through this year. So yes, I need writing to survive.

That and chocolate. Does anyone have chocolate? (I’ve somehow ran out of chocolate…)

Goals for 2021

- Successful launch of my debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet

- Write and revise Mary Bennet book 3

- Finish up a quick revision of an old steampunk mystery novel that I shelved for a few years

If I do these three things, I will be happy. (Also, I have to do the first two, because I’ve signed a contract, so…so I better go listen to some more Hamilton.)

Thanks for joining me on my writing journey!

(Also–side note. If you’re not subscribed to my newsletter, I sent out a newsletter today about how I recently deleted 100 pages from the aforementioned steampunk mystery novel. You can read about it by clicking on that link. And if you don’t want to miss future newsletters, subscribe below.)