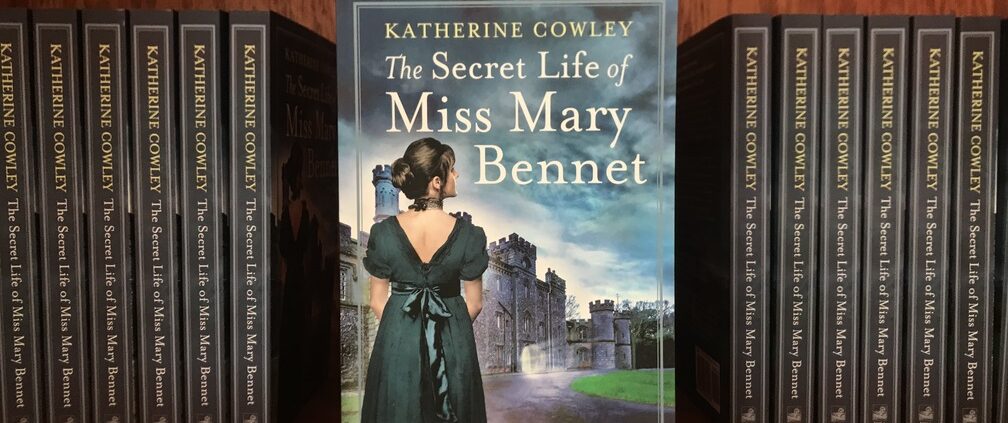

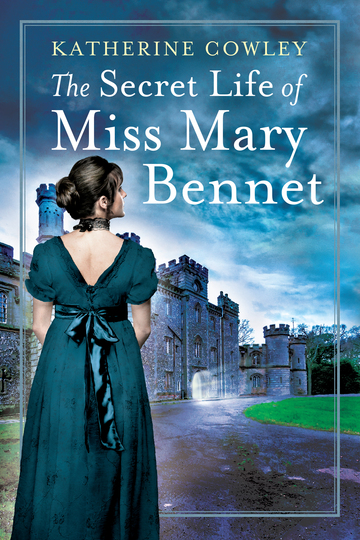

It’s Publication Day for The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet

The long-awaited day is here! My debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, is now out in the world. It tells the story of Mary Bennet, the often-overlooked middle sister…

Never underestimate the observation skills of a woman who hides in the background.

I started working on this novel in 2017, I found an agent for it in 2019, and my agent sold it to a publisher in 2020. And now, as of today, it is a published novel.

It’s currently available in print and ebook; it will be released as an audiobook in a few weeks. Here’s full links for how to order The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet.

For updates on books 2 and 3 in the series, make sure to sign up for my newsletter!

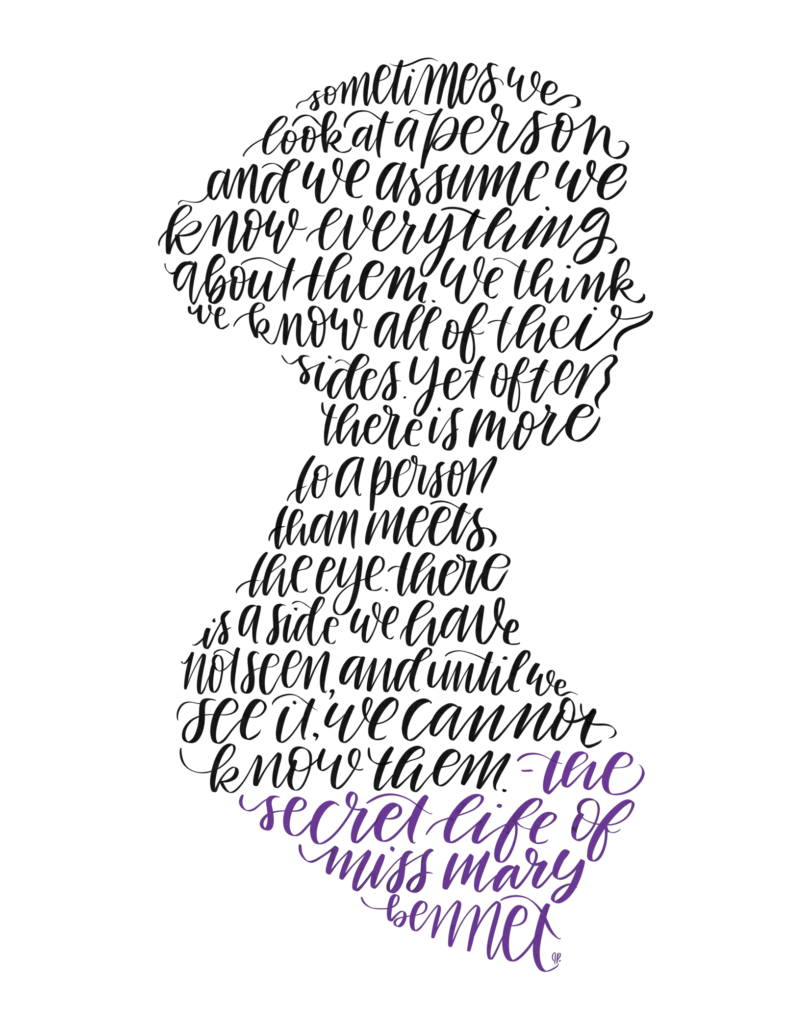

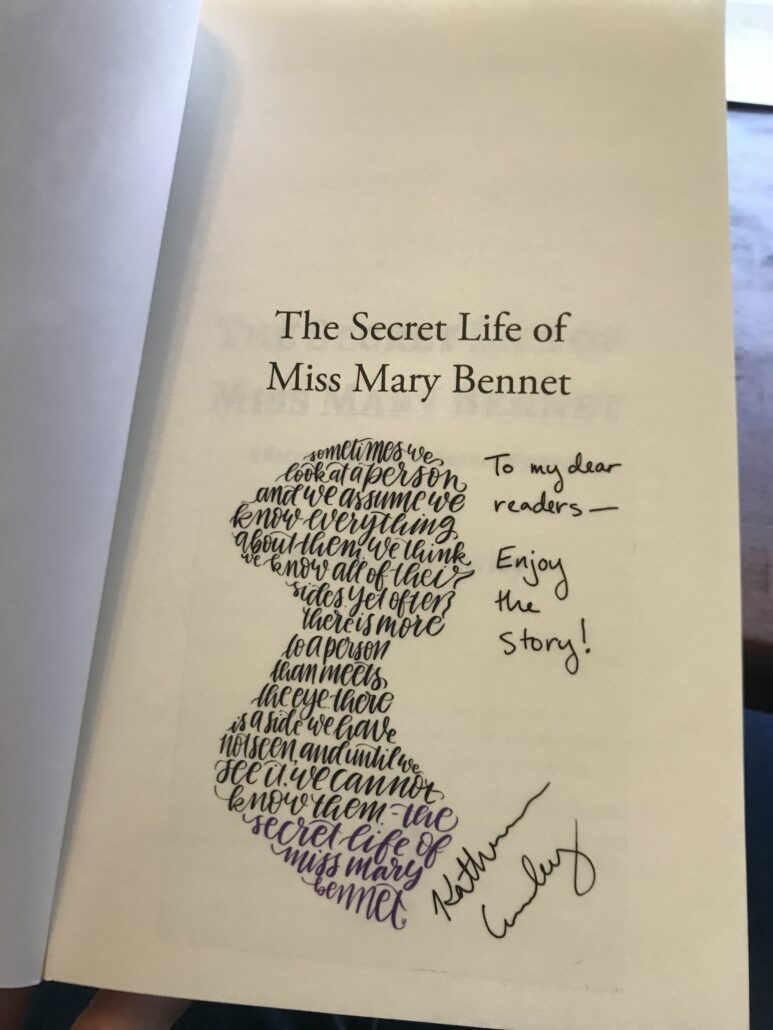

I also have a bookplate that I would love to mail to readers for free (while supplies last). Here’s what it looks like:

If you’d like your own complimentary bookplate or notecard to go with the book, please fill out this form.

Thank you for reading my books and supporting me as a writer! It means the world to me.

#33: Use Familiar and Invisible Settings

Jane Austen is not afraid to describe settings: a few posts back, I discussed the pages of setting description she uses when Elizabeth arrives at Pemberley. She also tends to focus more on setting when it’s relevant to a major plot turn or serves to reveal a character’s emotions.

Yet other times, Austen hardly describes the setting at all. Take, for instance, the Meryton Assembly, the ball where Jane meets Mr. Bingley for the first time and Elizabeth meets Mr. Darcy. It’s a crucial scene in Pride and Prejudice, yet the assembly room is not described:

When the party entered the assembly room, it consisted of only five altogether.

Never, at any point, does Austen describe the assembly room, its size or arrangement, its features. She does give a few other clues to the setting:

The report which was in general circulation within five minutes of his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year.

This gives the sense that people are talking to each other and spreading information. Also:

Mr. Bingley had soon made himself acquainted with the principal people in the room; he was lively and unreserved, danced every dance, was angry that the ball closed so early, and talked of giving one himself at Netherfield.

We know now that not everyone at this sort of setting is considered “principal,” or of a class where Mr. Bingley would be expected to meet them. Perhaps the most important part of the chapter is when Elizabeth overhears Mr. Darcy insulting her: “She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.” Every single adaptation arranges this moment quite differently, in part because Austen does not give copious details about the setting:

Elizabeth Bennet had been obliged, by the scarcity of gentlemen, to sit down for two dances, and during part of that time Mr. Darcy had been standing near enough for her to overhear a conversation between him and Mr. Bingley.

Most often it is for familiar settings that Austen employs a minimal amount of description.

A familiar setting is one which is familiar to the characters. It is a place where they have spent much time and often (though not always) feel comfortable. Because of its familiarity, the characters do not pay much attention to the setting. As a result of this the narrator, who is focalizing the perspective of a character, does not pay much attention to the setting.

In addition to mirroring the main character’s experience, providing a minimal description of a familiar setting does three things.

Invisible Settings

There are also times when Jane Austen uses an invisible setting—a setting that is not described or delineated in any concrete way.

An example of this is after the Meryton Assembly. The family has returned home, and Mrs. Bennet is describing the ball to Mr. Bennet (who did not attend). And then, we have a new chapter, which begins:

When Jane and Elizabeth were alone, the former, who had been cautious in her praise of Mr. Bingley before, expressed to her sister how very much she admired him.

From the previous chapter, it is safe to assume that they are probably at home. But are they in the library, a parlor, a bedroom? Is it still the same night or is it the next morning? Could they have gone to the garden? Are they still in their ball gowns or have they changed? None of this information is delineated: we only know that Jane and Elizabeth are alone.

Jane and Elizabeth have a beautiful, insightful conversation, throughout which we do not receive a single additional piece of information on the setting.

Invisible settings are not common—personally, I can’t think of a single piece of recently published fiction that has a truly invisible setting. And I don’t know if I could get away with writing an invisible setting—my critique partners and editors would probably call me out on it, and force me to at least give a few details to orient the reader and ground the scene. Yet Austen does it quite effectively, without leaving the reader disoriented.

To use a cinematography metaphor, when Austen employs an invisible setting, is it like she is filming a scene entirely using close ups and extreme close-ups, where we are seeing only the characters faces and expressions. It is an approach to point of view which keeps it so very fixed on a character or characters that there is never a chance to have a medium shot, long shot, or establishing shot which would place the characters in their surroundings.

Using Description within a Familiar Setting

At times, Jane Austen does give more detailed descriptions for familiar settings. Often this is to demonstrate emotion or to give deeper insight into a situation and character, such as when Elizabeth receives a letter from her aunt about Mr. Darcy:

Elizabeth had the satisfaction of receiving an answer to her letter, as soon as she possibly could. She was no sooner in possession of it, than hurrying into the little copse, where she was least likely to be interrupted, she sat down on one of the benches, and prepared to be happy; for the length of the letter convinced her that it did not contain a denial.

While only a paragraph, this description of a familiar setting provides a wealth of details that set the stage for a pivotal point in the novel. We not only see Elizabeth’s anticipation, but we see how she is consciously choosing a particular setting, what she sees as an ideal setting, for reading this letter.

At other times, details are given for familiar settings because something has made the setting less familiar or less comfortable.

When Lydia comes home with Mr. Wickham after their patched-up marriage, Wickham’s presence transforms the house from a familiar place to an unfamiliar one, with new rules and relationship negotiations. Suddenly, we receive descriptions of rooms and hallways and entryways which have never been described over the hundreds of pages that came before:

They came. The family were assembled in the breakfast room, to receive them. Smiles decked the face of Mrs. Bennet, as the carriage drove up to the door; her husband looked impenetrably grave; her daughters, alarmed, anxious, uneasy.

Lydia’s voice was heard in the vestibule; the door was thrown open, and she ran into the room.

And then, a little later in the scene we read:

Elizabeth could bear it no longer. She got up, and ran out of the room; and returned no more, till she heard them passing through the hall to the dining parlour. She then joined them soon enough to see Lydia, with anxious parade, walk up to her mother’s right hand, and hear her say to her eldest sister, “Ah! Jane, I take your place now, and you must go lower, because I am a married woman.

Jane Austen is a master of not over-describing her settings, and she often uses very minimal descriptions when it is a setting which is a familiar to her characters; as a result, when she does provide description of a familiar setting, it is often a powerful tool which impacts the reading experience.

Exercise 1: Write a short scene in a dynamic setting (one that has lots of movement or people or interest or many events). While the setting should be dynamic, it should also be one that you can expect modern readers to share some common knowledge of (for example, an amusement park, a casino, a bar, a city bus/train, a busy museum). As you write the scene, restrict yourself to giving only two or three details about the setting, which can only be described briefly (ideally one sentence or phrase).

Exercise 2: Create a new outline of a story, or do a post-draft outline of a story that you have written a complete draft for. For each scene or chapter, write down the setting and label it either “familiar setting or “unfamiliar setting.” If you’d like, you can become even more specific: “setting that is now familiar but was originally unfamiliar,” “familiar setting that feels unfamiliar/uncomfortable,” etc.

Analyze the results, and if you’d like, use this to help you write or revise your story.

Exercise 3: Let’s pollute the shades of Pemberley! How do we do that? By deigning to alter Jane Austen’s words. First you’ll add description of setting to one of Austen’s scenes, and then you’ll subtract or condense the description of setting from another one of her scenes.

The point of this exercise to examine how things change when you have more or less description, and consider why a lot of description might be useful in a certain context and why minimal description might be useful in another context.

Part 1: Add Details About Setting

Spend 5-10 minutes adding details about the setting to the Meryton assembly scene:

A report soon followed that Mr. Bingley was to bring twelve ladies and seven gentlemen with him to the assembly. The girls grieved over such a number of ladies, but were comforted the day before the ball by hearing, that instead of twelve he brought only six with him from London—his five sisters and a cousin. And when the party entered the assembly room it consisted of only five altogether—Mr. Bingley, his two sisters, the husband of the eldest, and another young man.

Mr. Bingley was good-looking and gentlemanlike; he had a pleasant countenance, and easy, unaffected manners. His sisters were fine women, with an air of decided fashion. His brother-in-law, Mr. Hurst, merely looked the gentleman; but his friend Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year. The gentlemen pronounced him to be a fine figure of a man, the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr. Bingley, and he was looked at with great admiration for about half the evening, till his manners gave a disgust which turned the tide of his popularity; for he was discovered to be proud; to be above his company, and above being pleased; and not all his large estate in Derbyshire could then save him from having a most forbidding, disagreeable countenance, and being unworthy to be compared with his friend.

Mr. Bingley had soon made himself acquainted with all the principal people in the room; he was lively and unreserved, danced every dance, was angry that the ball closed so early, and talked of giving one himself at Netherfield. Such amiable qualities must speak for themselves. What a contrast between him and his friend! Mr. Darcy danced only once with Mrs. Hurst and once with Miss Bingley, declined being introduced to any other lady, and spent the rest of the evening in walking about the room, speaking occasionally to one of his own party. His character was decided. He was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world, and everybody hoped that he would never come there again. Amongst the most violent against him was Mrs. Bennet, whose dislike of his general behaviour was sharpened into particular resentment by his having slighted one of her daughters.

Elizabeth Bennet had been obliged, by the scarcity of gentlemen, to sit down for two dances; and during part of that time, Mr. Darcy had been standing near enough for her to hear a conversation between him and Mr. Bingley, who came from the dance for a few minutes, to press his friend to join it.

“Come, Darcy,” said he, “I must have you dance. I hate to see you standing about by yourself in this stupid manner. You had much better dance.”

“I certainly shall not. You know how I detest it, unless I am particularly acquainted with my partner. At such an assembly as this it would be insupportable. Your sisters are engaged, and there is not another woman in the room whom it would not be a punishment to me to stand up with.”

“I would not be so fastidious as you are,” cried Mr. Bingley, “for a kingdom! Upon my honour, I never met with so many pleasant girls in my life as I have this evening; and there are several of them you see uncommonly pretty.”

“You are dancing with the only handsome girl in the room,” said Mr. Darcy, looking at the eldest Miss Bennet.

“Oh! She is the most beautiful creature I ever beheld! But there is one of her sisters sitting down just behind you, who is very pretty, and I dare say very agreeable. Do let me ask my partner to introduce you.”

“Which do you mean?” and turning round he looked for a moment at Elizabeth, till catching her eye, he withdrew his own and coldly said: “She is tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me; I am in no humour at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men. You had better return to your partner and enjoy her smiles, for you are wasting your time with me.”

Mr. Bingley followed his advice. Mr. Darcy walked off; and Elizabeth remained with no very cordial feelings toward him. She told the story, however, with great spirit among her friends; for she had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in anything ridiculous.

Part 2: Subtract Details About Setting

Spend 5-10 minutes subtracting or condensing details about the setting from the scene when Elizabeth first sees Pemberley:

Elizabeth, as they drove along, watched for the first appearance of Pemberley Woods with some perturbation; and when at length they turned in at the lodge, her spirits were in a high flutter.

The park was very large, and contained great variety of ground. They entered it in one of its lowest points, and drove for some time through a beautiful wood stretching over a wide extent.

Elizabeth’s mind was too full for conversation, but she saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view. They gradually ascended for half-a-mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. It was a large, handsome stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills; and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. Its banks were neither formal nor falsely adorned. Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!

They descended the hill, crossed the bridge, and drove to the door; and, while examining the nearer aspect of the house, all her apprehension of meeting its owner returned. She dreaded lest the chambermaid had been mistaken. On applying to see the place, they were admitted into the hall; and Elizabeth, as they waited for the housekeeper, had leisure to wonder at her being where she was.

The housekeeper came; a respectable-looking elderly woman, much less fine, and more civil, than she had any notion of finding her. They followed her into the dining-parlour. It was a large, well proportioned room, handsomely fitted up. Elizabeth, after slightly surveying it, went to a window to enjoy its prospect. The hill, crowned with wood, which they had descended, receiving increased abruptness from the distance, was a beautiful object. Every disposition of the ground was good; and she looked on the whole scene, the river, the trees scattered on its banks and the winding of the valley, as far as she could trace it, with delight. As they passed into other rooms these objects were taking different positions; but from every window there were beauties to be seen. The rooms were lofty and handsome, and their furniture suitable to the fortune of its proprietor; but Elizabeth saw, with admiration of his taste, that it was neither gaudy nor uselessly fine; with less of splendour, and more real elegance, than the furniture of Rosings.

“And of this place,” thought she, “I might have been mistress! With these rooms I might now have been familiarly acquainted! Instead of viewing them as a stranger, I might have rejoiced in them as my own, and welcomed to them as visitors my uncle and aunt. But no,”—recollecting herself—“that could never be; my uncle and aunt would have been lost to me; I should not have been allowed to invite them.”

This was a lucky recollection—it saved her from something very like regret.

She longed to enquire of the housekeeper whether her master was really absent, but had not the courage for it. At length however, the question was asked by her uncle; and she turned away with alarm, while Mrs. Reynolds replied that he was, adding, “But we expect him to-morrow, with a large party of friends.” How rejoiced was Elizabeth that their own journey had not by any circumstance been delayed a day!

Part 3: Reflection

Now reflect! What did you learn about what Austen was doing and why? Are there other effective ways that these scenes could be written?

Inspirations for The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet: The Scarlet Pimpernel

Being a teenager can be hard. That’s something Mary Bennet from Pride and Prejudice can attest to, and my experiences as a teenager definitely influenced the character of Mary in my novel The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet. Mary is a bit of an awkward teenage, and others are not always kind to her for it. In my novel, she is leaving her teenage years and entering adulthood, but she is still impacted by her teenage struggles.

For me, one of the hardest points in my teenage years was when, a few weeks before I turned thirteen, our family moved across the country, from Washington state to Connecticut. I was very much in denial, so much that I didn’t tell my friends at school that I was moving until a few days before winter break, when the move would take place. If I didn’t talk about it, it wouldn’t happen, right? But happen it did.

I really struggled with the adjustment…I had moved, as the crow flies, 3986 miles, and left everything I’d known. I found it really strange to suddenly be at a school where the popular girl in your home room would make fun of you if your socks went above your ankle because apparently that was a major fashion faux paus.

But there was a shining light for my first few months in Connecticut: I went with my mom to see a stage production of The Scarlet Pimpernel.

Before we’d moved, I’d been taking an online math class because the math class I needed didn’t fit into my schedule. This was 1999, and at that point, we didn’t even have internet at home, so I was doing all of it at school in the computer lab during my math period. And I was going at a fast pace—in a single semester, I was nearing the end of a two-semester math class. My mom saw how close I was and gave me a challenge: if I could finish the class before we moved, then we would do something really amazing in Connecticut.

I finished the math class, and in early 2000, my mom took me to see the musical The Scarlet Pimpernel in New Haven, Connecticut. The Scarlet Pimpernel had just left Broadway, and some of the original cast were members of the touring cast.

It was life-changing.

I loved the story, the music, and the characters, especially the Scarlet Pimpernel and Marguerite. I loved the mask that the Scarlet Pimpernel wears for the world—no one would ever suspect that the frivolous, clothing-obsessed Sir Percy Blakeney was the enemy wanted by the guillotine. In one of the songs, the British upper class is speculating on the identity of the Scarlet Pimpernel, and Sir Percy keeps joking, “The fellow’s me!” and the irony is that it really is him and no one believes him.

My well-loved copy of the vocal music from the musical.

We bought the CD and the vocal music, and for years, my favorite song was “The Riddle”:

You turn and someone betrays you.

Betray him first, and the game’s reversed.

For we all are caught in the middle

Of one long treacherous riddle.

Can I trust you? Should you trust me, too?

I loved this sense of the risk of having a secret identity, the inherent risk of being discovered, and the constant inability to know who you could trust. I also couldn’t stop thinking about the sense that you are changed by participating in this sort of game, which makes it harder to find and recognize the truth.

Fast-forward to a few years ago. When I was developing the character of Miss Mary Bennet for my book, I kept The Scarlet Pimpernel in mind. (Not just the musical, but also the brilliant 1982 movie. Confession: I’ve never actually read the book The Scarlet Pimpernel.) I wanted Mary to be like the Scarlet Pimpernel, for no one would ever suspect that she could do great things. No one would ever suspect that she was sneaking around, gathering clues and solving mysteries.

A number of other works inspired me as I wrote my novel (most notably, Jane Austen), but one of my favorite inspirations for Miss Mary Bennet is The Scarlet Pimpernel.

The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet will be released worldwide on April 22, 2021. I am so excited to share the story with everyone!

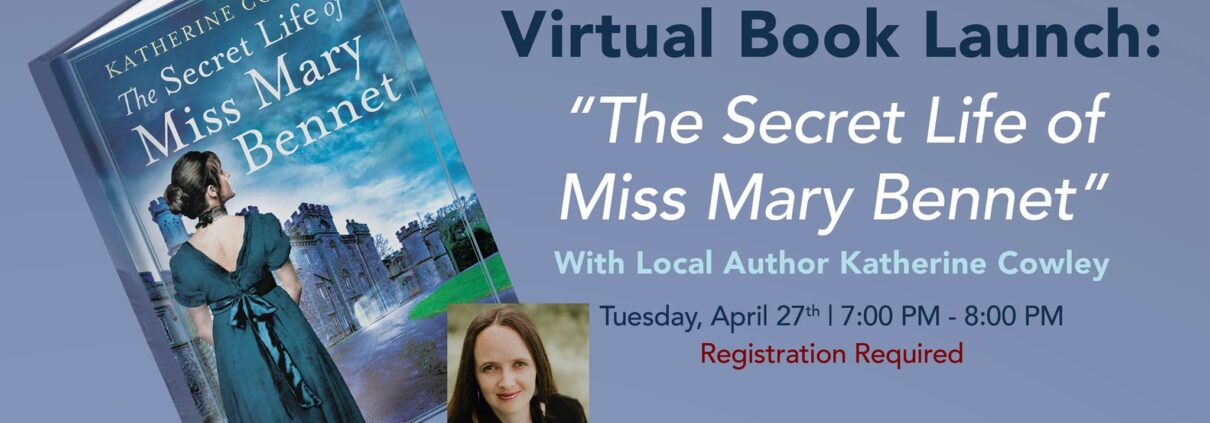

Events: April 2021 and Book Club Visits

I mentioned these upcoming events in my newsletter, but I wanted to do a quick blog post about them.

First, my April events, which are all virtual.

Virtual Launch Party Hosted by the Portage Public Library: April 27th at 7 p.m. EDT.

I would love to see you at the virtual launch party for The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet! You need to RSVP to the event in advance so the library can email you the Zoom link.

Virtual SCBWI Michigan Conference: April 23rd-25th

I will be giving a presentation on the final day of this writing conference, which is focused on writing your story from start to finish. You don’t need to be in Michigan or a member of SCBWI to attend.

Ongoing Events

Katherine Crashes Your Book Group

I want to crash your book group. I’m serious.

I’m a member of two book groups, so theoretically, that would be enough book groups for me. But it’s not.

If your book group reads The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, then I would love to crash your book group with a video call for the last fifteen minutes of your discussion. I will answer questions and provide insights into the book. If this is something you’re interested in, send me an email at kathy@katherinecowley.com.

Keep Up-to-Date on Upcoming Events

If you’d like to stay up-to-date on my upcoming events, sign up for my newsletter. I’ll also keep events updated on the events page of my website.

Book Katherine for an Event

For writing workshops, school visits, or any other event, please send me an email at kathy@katherinecowley.com.

#32: Use Setting to Complement or Contrast Emotion

In the last lesson, I discussed the advantages of using a distinctive setting in a major plot turn. In addition to assisting the plot, a setting is one of the most powerful ways to reveal a character’s emotions.

In Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park, the main character, Fanny Price, lives with her aunt and uncle and cousins. Fanny is often mistreated and ignored, but when her cousin Maria is married, both of Fanny’s female cousins—Maria and Julia—travel to London. Everyone’s treatment of Fanny improves, and she becomes a more essential and more valued part of the household.

Her friendship with a neighbor, Miss Crawford, also increases. One day, while Fanny is visiting Miss Crawford, the two are walking around the shrubbery at the parsonage, and they stop to sit on a bench. They are both in the exact same setting at the exact same time, but they both engage with it differently, and how they engage and interact with the setting provides insight into their emotions:

“This is pretty—very pretty,” said Fanny, looking around her as they were thus sitting together one day: “Every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with its growth and beauty. Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing; and now it is converted into a walk, and it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or an ornament; and perhaps in another three years we may be forgetting—almost forgetting what it was before. How wonderful, how very wonderful the operations of time, and the changes of the human mind!”

Fanny not only notices the growth and development of the setting, but she also eloquently expresses her observations. For the reader, Fanny’s musings on the shrubbery are not just a matter of an improved landscape: her musings reflect on how Fanny prefers her new role within the world. Previously, her family “never thought of [her] as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing,” but like the shrubbery, she is now flourishing. And because she is flourishing, she notices the shrubbery.

On the contrary, this is Miss Crawford’s reaction:

Miss Crawford, untouched and inattentive, had nothing to say.

Miss Crawford is naturally less interested in nature, but this character difference is not the full story. In the subsequent paragraphs, it begins to become clear that Miss Crawford is wrapped up in her own thoughts and reflections, as she tries to figure out what her future will look like. She is not a viewpoint character in this scene, yet still we glimpse her emotions by the very fact that she does not notice the setting and is unable to respond to Fanny’s enthusiasm.

Complements and Contrasts

When using setting to reveal emotion, the writer can:

In the above example, the emotion was revealed through speech, action, inaction, and awareness, all of which related or were in reference to the setting. Another effective method of revealing emotion is through the description of setting within the narrative.

Using the Setting to Complement Emotions

In Mansfield Park, Fanny’s uncle Lord Bertram becomes angry with her when she refuses an offer of marriage. He sends her back to her parents, which puts her in a setting that she has not interacted with since she was a young girl. How she feels about this is made clear by the narrator’s insights into her perception of the setting:

She was then taken into a parlour, so small that her first conviction was of its being only a passage-room to something better, and she stood for a moment expecting to be invited on; but when she saw there was no other door, and that there were signs of habitation before her, she called back her thoughts, reproved herself, and grieved lest they should have been suspected.

Several chapters focus almost entirely on Fanny’s interaction with the setting. The setting is not just her parents’ house; the setting is also the people in it (all of her many siblings, most of who she has no connection to), as well as and the behaviors and expectations associated with the house. In one passage, we read:

But though she had seen all the members of the family, she had not yet heard all the noise they could make.

Austen goes on to describe, in great detail, the hustle and bustle and the yelling and the arguing,

the whole of which, as almost every door in the house was open, could be plainly distinguished in the parlour, except when drowned at intervals by the superior noise of Sam, Tom, and Charles chasing each other up and down stairs, and tumbling about and hallooing.

Fanny was almost stunned. The smallness of the house, and thinness of the walls, brought every thing so close to her, that, added to the fatigue of her journey, and all her recent agitation, she hardly knew how to bear it.

There is never a need for Austen to state, “Fanny was not happy with this move and did not feel comfortable with her family. She felt unloved and unwanted.” None of these things need to be said, because we experience through it as Fanny experiences the setting. At the end of one of the chapters, the narrator does state Fanny’s emotions more directly:

In a review of the two houses, as they appeared to her before the end of a week, Fanny was tempted to apply to them Dr. Johnson’s celebrated judgment as to matrimony and celibacy, and say, that though Mansfield Park might have some pains, Portsmouth could have no pleasures.

However, this more direct statement of emotion works because of the artistry of it, because it is a direct revelation of Fanny’s internal thoughts, and because this direct statement of emotion has been earned. We have already experienced the emotion with Fanny by experiencing the setting with her. And so when this statement is made, we agree with her and we feel for her.

Using the Setting to Contrast Emotions

At other times, it can be effective to use the setting to provide a contrast to the character’s emotions. A good, beautiful day could be contrasted with a character’s depressions, just as a terrifying storm could contrast with a character’s happiness.

Near the beginning of the novel, when a young Fanny arrives at Mansfield Park, the wonderful, grand house provides a clear contrast to her emotions, actually serving to make her feel worse:

The grandeur of the house astonished, but could not console her. The rooms were too large for her to move in with ease; whatever she touched she expected to injure, and she crept about in constant terror of something or other; often retreating towards her own chamber to cry.

When a positive setting contrasts with a negative emotion, it can serve to alienate the character from their surroundings, as occurs in this example. This can make the character’s negative emotions feel even weightier to the reader. When a negative setting contrasts with a positive emotion, the character seems to transcend their setting. This can make the character’s positive emotions seem greater or more powerful to the reader.

Using the Setting Both to Complement and Contrast Emotions

Some settings both complement and contrast emotions. This can occur over the course of a novel, as a character’s relationship with the setting changes.

This can also occur within a single scene. When a setting both complements and contrasts emotions in a single scene, it often serves to highlight the complexity of human emotion as well as our nuanced experiences with our surroundings.

The following passage in Mansfield Park occurs when Fanny is still at her parents’ home. She is dreading receiving bad news in the mail. Note how the narrator calls attention to the fact of what the bright sunlight should do versus what it actually does, and how this transitions to Fanny noticing aspects of the setting which reflect her discomfort (such as the low-quality blue milk with motes and the increasingly greasy butter and bread):

The sun was yet an hour and half above the horizon. She felt that she had, indeed, been three months there; and the sun’s rays falling strongly into the parlour, instead of cheering, made her still more melancholy, for sunshine appeared to her a totally different thing in a town and in the country. Here, its power was only a glare: a stifling, sickly glare, serving but to bring forward stains and dirt that might otherwise have slept. There was neither health nor gaiety in sunshine in a town. She sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust, and her eyes could only wander from the walls, marked by her father’s head, to the table cut and notched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca’s hands had first produced it.

A bright cheery day is now a curse for Fanny—she normally loves the sun, but not now. Not in this context of this setting, and not in this context of her own emotional agony. The sun contrasts with her emotions until it is subverted into complementing her negative emotions.

In Conclusion

Just as Jane Austen does, we can use the setting to reflect or contrast with a character’s emotions. Often, this is more effective than just stating the emotion, and it allows the setting to perform work on multiple levels of the novel.

Exercise 1: One Setting, a Multitude of Possible Emotions

Photo by Mario Cuadros from Pexels

A single setting could be described in very different ways, depending on the character’s emotion. Consider the above photograph. Now write three short descriptions of the character within this setting, each which conveys a different emotion. Aim for a one to four sentence description, and choose from the following emotions:

- Fear

- Excitement

- Resignation

- Love

- Fatigue

- Concern for someone else

Exercise 2:

Choose a novel. Now find three different points in the novel which describe the setting while providing insight into emotion. Does the setting complement or contrast the emotion? Does it do both? What specific word choice and sentence structure helps produce the desired emotion?

Exercise 3:

Option 1: As you write a scene, consciously include details about the setting which either complement or contrast with the character’s emotions.

Option 2: Take an early draft of a scene you have written and revise it, focusing on using the setting to shine a light on the character’s emotions.

#31: Use a Distinctive Setting for Major Plot Turns

Many of the scenes in Jane Austen’s novels occur in what, for her characters, would be ordinary settings—drawing rooms and walks where they had been many times before. We’ll talk, in a few weeks, about how to use familiar settings.

But sometimes Austen uses very distinctive settings for her scenes, and this often happens when there is a major plot turn in the story.

A major plot turn is when both the story and the characters undergo a large shift. Something happens which irrevocably changes the future direction of the plot, and has a profound impact on character and relationship arcs.

In her novel Persuasion, Jane Austen gives her characters a distinctive setting, unlike the rest in the book, when a number of the characters take a trip to the town of Lyme Regis.

A modern view of Lyme Regis by Alison Day (limited Creative Commons license)

Three of the characters who travel to Lyme Regis are our main character, Anne Elliot, the man she turned down years before, Captain Wentworth, and his current love interest, Louisa Musgrove.

I previously talked about the Anne-Wentworth-Louisa trio in a post about making things hard for your character. In sum, when Anne and Captain Wentworth became engaged, Anne was persuaded by family members and friends to break off the engagement. Wentworth still has not forgiven her for this. One of the things Wentworth values about Louisa is that she is not easily persuadable—she will go her own way.

Fast forward to Lyme Regis. Bringing the characters to this new, distinctive setting first allows them to meet or encounter new characters who will be key to the story, including Captain Benwick and Anne’s cousin, Mr. Elliot.

Distinctive settings are unfamiliar to characters, which heightens the awareness of the setting for both the characters and the reader. When in a distinctive setting, the characters have a whole additional layer of things to navigate: new physical objects, new or unfamiliar expectations, and as a result…

Distinctive settings often draw out peoples strengths and weaknesses, demonstrate who they really are, and provide opportunities for characters to transform in either a positive or a negative direction.

At Lyme Regis, a number of the characters take a walk along the Cobb, which is a wall near the harbor. There is a heightened awareness of the setting, which is distinctive enough to bring to Anne’s mind the poetry of Byron as she walks with Captain Benwick:

Lord Byron’s ‘dark blue seas’ could not fail of being brought forward by their present view, and she gladly gave him all her attention as long as attention was possible.

In the following paragraph, which is one of the biggest, most dramatic events in Persuasion, we see how the setting draws out Louisa’s firmness of character and the way she is unyielding to persuasion. While Captain Wentworth has always seen this characteristic as a virtue, the negative side of it is made clear.

There was too much wind to make the high part of the new Cobb pleasant for the ladies, and they agreed to get down the steps to the lower, and all were contented to pass quietly and carefully down the steep flight, excepting Louisa; she must be jumped down them by Captain Wentworth. In all their walks, he had had to jump her from the stiles; the sensation was delightful to her. The hardness of the pavement for her feet, made him less willing upon the present occasion; he did it, however; she was safely down, and instantly, to shew her enjoyment, ran up the steps to be jumped down again. He advised her against it, thought the jar too great; but no, he reasoned and talked in vain; she smiled and said, ‘I am determined I will:’ he put out his hands; she was too precipitate by half a second, she fell on the pavement on the Lower Cobb, and was taken up lifeless!

A picture of steps on the Cobb, which is one of the sets of steps that Austen may have been describing in the novel. Image by Chris Talbot, Creative Commons license.

Almost all of the characters completely panic and are rather useless in this sort of situation. Except for Anne. Here we see her kindness, her perceptiveness, her rationality, and her ability to act in the face of challenge.

“Go to him, go to him,” cried Anne, “for heaven’s sake go to him….Rub her hands, rub her temples; here are salts,–take them, take them.”

Captain Benwick obeyed, and Charles at the same moment, disengaging himself from his wife, they were both with him; and Louisa was raised up and supported more firmly between them, and every thing was done that Anne had prompted, but in vain; while Captain Wentworth, staggering against the wall for his support, exclaimed in the bitterest agony,

“Oh God! her father and mother!”

“A surgeon!” said Anne.

He caught the word; it seemed to rouse him at once, and saying only, “True, true, a surgeon this instant,” was darting away, when Anne eagerly suggested,

“Captain Benwick, would not I be better for Captain Benwick? He knows where a surgeon is to be found.”

Every one capable of thinking felt the advantage of the idea[.]

Jane Austen uses a number of techniques in this passage to create emotional intensity. After Louisa’s fall, descriptions of the setting and people and people’s behavior are very short and concise. Her use of punctuation changes, paragraphs not ending with full stops before leaping into the next paragraph. And short snippets of dialogue are stacked on each other with almost no interruption.

A distinctive setting, like the Cobb at Lyme Regis, seems a fitting backdrop for such a pivotal event that impacts the entire trajectory of the novel.

Making an Ordinary Setting Distinctive

Sometimes distinctive settings are big and new and grand and different. Yet at other times, Jane Austen takes an ordinary setting and makes it distinctive in some way, and then uses this ordinary yet distinctive setting for a major plot turn.

An example of this is Mr. Elton’s proposal to Emma, in the book Emma. This proposal is key, not just because it is a proposal which she rejects, but because it is the start of Emma’s awareness that her judgment can be faulty (she thought Mr. Elton was in love with her friend Harriet, but he is actually in love with her).

The proposal occurs in a carriage, a very ordinary setting for an Austen character, yet what makes it distinctive is that Emma and Mr. Elton were never meant to be in a carriage alone together, and they only are because of a mix-up caused by other characters.

It is not common for a man and a woman to be in a carriage by themselves. This suddenly distinctive setting puts these two characters alone and unsupervised, when they would not normally be so. Mr. Elton decides to seize this opportunity to propose. The setting also serves to trap the characters: they are stuck in a moving box together, which adds to the pressure. During the proposal Emma feels trapped, and then after he is denied, Mr. Elton is also trapped both literally and figuratively.

A distinctive setting—whether it is grand and full of danger like the Cobb, or a familiar setting made distinctive like Emma’s carriage—is a powerful place to set a major plot turn, as it can make the plot possible, heighten awareness and tension, and draw out characters’ strengths and weaknesses.

Exercise 1: Choose a key scene from a story you have written, and revise the scene either by:

- Editing the setting to make it more distinctive (which will impact your description as well as how your character interact with and within the setting).

- Rewriting the scene with a new setting that can do more to assist with this major plot point.

Exercise 2:

Choose a book or a film, and find a scene with a distinctive setting in terms of landscape, architecture, cultural/historical significance, etc.

How does the use of this setting impact the plot and the character? What strengths and weaknesses of the characters does it manifest? How does this setting fit within the context of the other settings used in the story?

Exercise 3:

Consider the following list of ordinary places. Add a description to each to show how you could make them distinctive, in a way that might open up storytelling possibilities. (This could be anything, for example, something happening within the place, who is inside, how this place differs from other places like it, etc.)

- A grocery store

- A school bus

- A bar

- A movie theater

- A kitchen