#1: Make Your Character Want Something

The key components of story: plot character

At the heart of any story are two fundamental components: character and plot. There is a lot of debate about whether character or plot is more important, and both need to be addressed at every stage of the writing process. Yet there is an underlying principle that distills both character and plot.

Your main character needs to want something.

In Jane Austen’s novel Emma, the main character, Emma Woodhouse, wants to bring others happiness (and herself entertainment) by playing matchmaker. At the beginning of the book she sets herself on this path while speaking of her success in matching her dear friend and governess, Miss Taylor, to Mr. Weston:

“I made the match myself. I made the match, you know, four years ago; and to have it take place, and be proved in the right, when so many people said Mr. Weston would never marry again, may comfort me for any thing.”

Mr. Knightley shook his head at her. Her father fondly replied, “Ah! my dear, I wish you would not make matches and foretell things, for whatever you say always comes to pass. Pray do not make any more matches.”

“I promise you to make none for myself, papa; but I must, indeed, for other people. It is the greatest amusement in the world! And after such success you know!”

Illustration by C.E. Brock, from a 1909 edition of Emma

The wants of a character reveal their internal character and personality.

Emma believes she can be a matchmaker because she believes she understands people better than they understand themselves. Not only does she find herself superior to others, but she is used to getting what she wants.

The wants of a character create plot.

Emma’s desire to make matches leads to most of the action (and comedy) of the novel, such as her prolonged attempt to set her friend Harriet Smith up with the vicar, Mr. Elton.

Whether you’re brainstorming or revising a story, make sure your main character wants something, and that this want is manifest throughout the narrative.

How do you show character wants and motivations?

One of the most powerful ways to show what a character wants is through their dialogue, as seen in the example from Emma. Dialogue is not just about communication: it is a tool we use to assert our identities in the world, to create change, and to influence other characters.

What a character wants should also be shown through action. Emma arranges endless opportunities for Harriet and Mr. Elton to spend time together. At one point she is on a walk with them and she intentionally breaks her shoelace so she can fall behind, giving them the opportunity to be alone.

A further method that can be used to show character wants and motivation is through description. Emma notices every time Mr. Elton looks in Harriet’s direction, and the description reflects her motivation and hopes.

Exercise 1: Think of one of your favorite books or movies. What does the main character really want? Share your response in the comments.

Exercise 2: Whether you’re writing a novel, a short story, or a picture book, your main character should want something. Write a manifesto from their point of view about what they want, why they want it, and what they are willing to do to get it. This could be a single paragraph or a full page.

Exercise 3: Rewrite the following short scene about a woman named Mariah. The catch: you must add a strong character want. This could be any want, in any genre. For example:

- To be a matchmaker

- To find a valuable clue that will help her stop an assassin

- To be on time to something in her life, for once

Whether you choose one of these sample wants or your own, the character’s want should have an impact on the dialogue, the action, and the description.

Mariah walked up to the ticket counter. “One ticket for Ocean’s 8. The 7:00.”

The man at the counter nodded, not even looking up at her. As he made the selections on his computer, her eyes fell on his name tag. “Markus.” Her eyes moved back up to his face, and this time, she looked past the glasses and the beard. It really was Markus. She hadn’t seen him in years, not since high school graduation.

“Markus Santos?”

At this, he looked up from the screen. It took a moment, but realization dawned on his face. “Mariah. How are you?”

“Pretty good. How about you?”

“Great,” he said, but not very convincingly. “That’ll be $10.25.”

She inserted her credit card.

“Are you seeing this by yourself?” he asked.

“No, I’m meeting friends. They already have their tickets.”

She removed her credit card and he handed her the ticket.

“Have a nice night,” he said with a nod. There was no trace of the smiles he used to give to everyone.

“You too,” she said. She entered the theater.

Introduction to Jane Austen Writing Lessons

It is a truth universally acknowledged that if you wish to write well, you should learn from the very best writers.

In other words, you should read Jane Austen.

I do not find this to be a great sacrifice.

Elizabeth Bennet in the 2005 film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice

Jane Austen Writing Lessons

I am a writing teacher by profession and a long-time Janeite. Jane Austen Writing Lessons is my attempt to combine these two interests by creating a series of writing lessons based on the books of Jane Austen.

What will these lessons look like?

Each writing lesson will focus on a principle of creative writing. I will address how to use this principle, examine how Jane Austen uses the principle in one of her works, and then provide writing exercises that apply the principle. While the examples draw from the writings of Jane Austen and other Austen-inspired works, the principles can be applied to writing in any genre, and the writing exercises provide the opportunity to apply these principles in a variety of ways.

The first ten lessons address big picture principles for writing. After that, sets of lessons will go into depth on specific topics, like dialogue.

The Benefits of Writing Exercises

Musicians practice scales to teach their fingers to move in certain patterns. The coach of a sports team runs drills to prepare the players for different things that might happen on the field or on the court.

Writing exercises fulfill the same purpose: they are a chance to exercise or practice a principle in order to internalize it and be prepared to use it appropriately in your writing.

In my years of teaching writing, I have found that learning about a principle is rarely enough. Writers learn the principles best when they practice them, and writing exercises are an easy, contained way to do this.

Who Am I?

I have an MA in Rhetoric and Composition and focused my studies on the teaching of writing. I have taught writing classes at Mesa Community College and Brigham Young University, and I currently teach writing at Western Michigan University.

My debut novel, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, will be released in April 2021 by Tule Publishing. I also have over a dozen published short stories and novellas.

Visit the Jane Austen Writing Lessons homepage to view all of the writing lessons index.

The Mary Bennet Draft from COVID-19

I recently got a three-book deal for the trilogy which begins with The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet. Which means I sold one completed book, one partially completed book, and one book that exists entirely in my imagination.

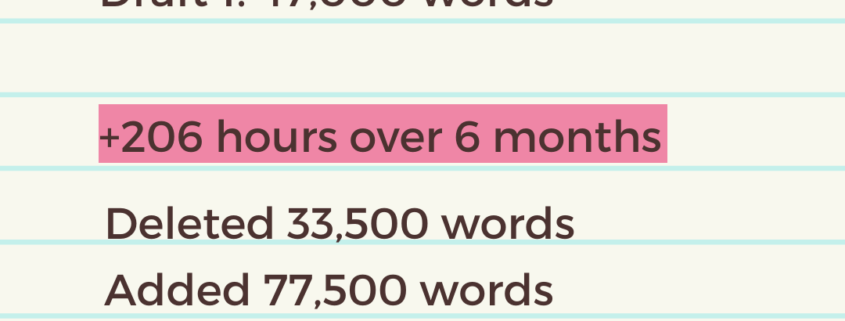

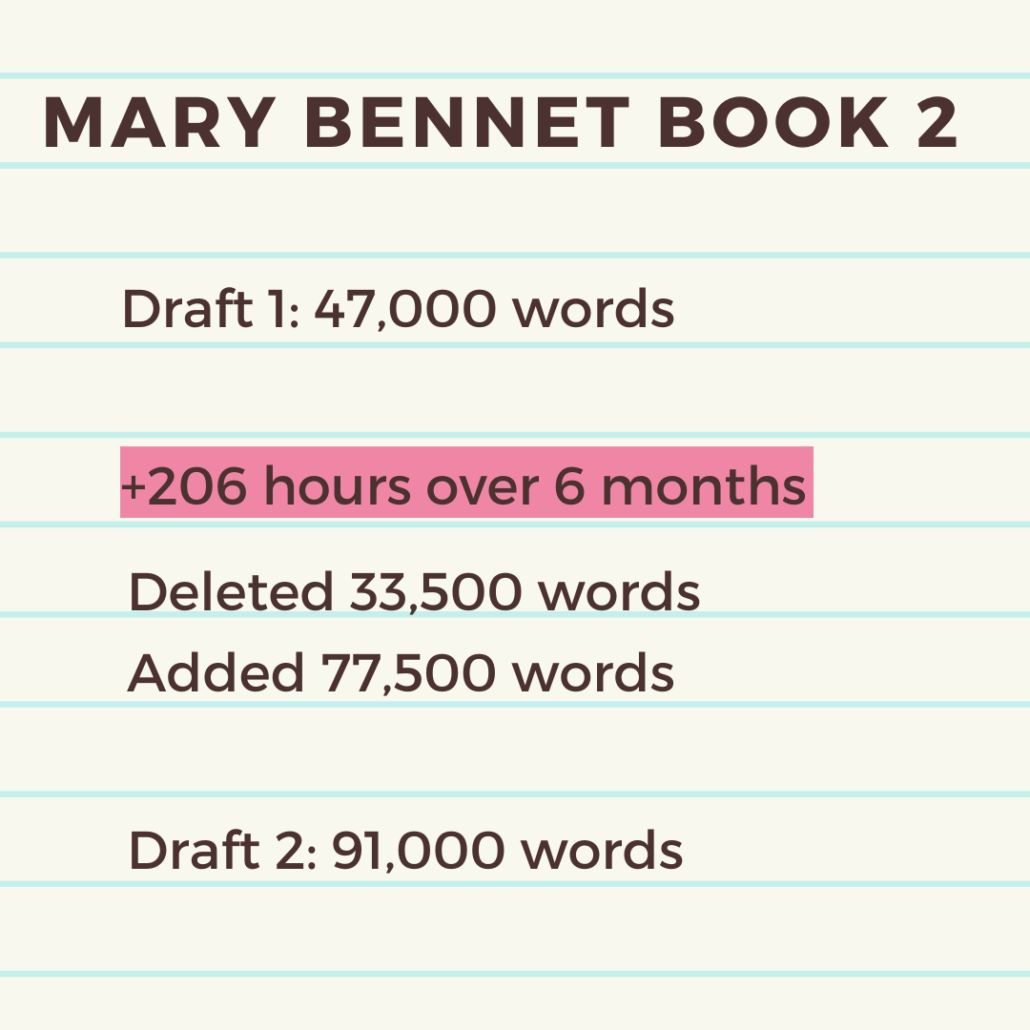

The partially completed book is currently known as Mary Bennet Book 2. Clever, I know. Fortuitously, I had accidentally written a first draft of book 2 while I was writing the first draft of book 1. When I got to the end of the draft, I realized it had two sets of characters, two completely different locations, two mysteries, two internal characters arcs… I had written two books, which I proceeded to chop in half. (Accidentally writing a draft is highly recommend, because you get two drafts for the price of one.)

So fast-forward to January 2020, when we were all naive and thought this year would be a lot more pleasant than it has turned out to be. My agent was sending out my first book to publishing houses, but she had the descriptions for books 2 and 3 on hand in case any of the publishers were interested in the whole series. This provided great motivation for me to make progress on book 2.

I opened the file for book 2. I already knew it was missing a few main characters that needed to be a part of the book, but as I looked at it, I realized that it had no plot. I mean, things happened, including two awesome spying-at-ball scenes, an explosion, mistaken identities, a conspiracy, etc. etc. etc. But still, there was no plot, no overarching mystery strong enough to hold all these cool scenes and ideas and subplots together.

And so I began the lengthy process of outlining, researching, plotting, deleting, and writing.

January. February. March. April. May. June. Goals I set for myself came and went. My kids were sent home from school. My part-time job (teaching first-year writing at WMU) went from in-person to online. Michigan had weeks where we had hundreds of COVID-19 deaths every single day. I struggled with anxiety about life, the universe, and everything. And still I put what I could into this book, even when it wasn’t much. I woke up at 6 a.m. almost every day of the year so I could sneak in some writing before the kids woke up, and I wrote during their afternoon movie time. It felt like I was building a mountain, one tiny spoonful of dirt at a time. But it added up.

I don’t think I’ve ever deleted quite so much in a draft. There was a full chapter I deleted and a number of other scenes, but most of the deletions came from deleted paragraphs and sentences.

206 hours is also the most time I have ever spent on a draft. Previously, the longest draft had taken 110 hours. (The first draft of Mary Bennet 1 took 140 hours, but as I mentioned before, it was actually the first draft of 2 books.)

COVID-19 definitely made this draft harder to write, but honestly, it was a challenging draft even in January and February. I can attribute this to three factors:

- I have become a better writer

As I revised the first Mary Bennet book, I learned a lot about plot and character and the mystery genre. Which meant that I had a whole new bunch of tools and lenses to take to this book–which meant that I could see how far it was from what it could become, and knew a lot of what it would take to get there. In my case, becoming a better writer has not made me a faster writer.

- I was doing complicated/challenging things

In Mary Bennet 2, I’m doing some complicated things structurally, and I have a large cast of characters. I have a number of chapters where I have 10 important characters in play and am interweaving the plot and three or four subplots at the same time. This is insane, I do not recommend it, and it challenged me as a writer. Also, these scenes are some of the best in the book.

- It took an eternity to figure out the ending

I am an outliner, but I still figure out a lot of things about what works and what doesn’t through the process of writing. I outlined before the first draft, and I outlined before the second draft, but for the life of me, I could not figure out the ending. (I knew who the villain was and a few key components that needed to be in there, but nothing else.) And I spent months thinking about the ending as I revised the other chapters and added new material. In a very uncharacteristic move for me (proud outliner that I am) I did not actually figure out the ending until it was time to write it.

Now that draft two of Mary Bennet Book 2 is done, I’ve sent it off to several critique partners. Then it will be another round of edits (theoretically less painful) and then another before I turn it in to the publisher.

Meanwhile, I should be getting feedback from my editor soon on the first book, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet. I’m really excited to edit it and get it ready for its release in April 2021.

I Got a Book Deal!

There is no way for me to express my excitement for the news I am about to share, so I will simply share it: I have a three-book deal with Tule Publishing!

My incredible agent, Stephany Evans, negotiated a three-book deal with Tule for The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet and its two sequels. The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet will be published in Spring 2021, and the second and third books will be published in 2022.

Here’s the blurb for the first book:

Of the five Bennet sisters, Jane is beautiful, Elizabeth is clever, and Kitty and Lydia are silly. Mary is the dull, plain sister . . . or so she wants everyone to think. She is actually a spy.

After Mr. Bennet’s death, Mary is left with no fortune. Rather than relying on direct family members for support, Mary accepts an invitation to stay with a distant relative, Lady Trafford, at the mysterious Castle Durrington. Lady Trafford gifts Mary with private tutoring and personal attention, but Mary cannot ignore Lady Trafford’s lies, secrets, and manipulations, which may put their seaside community at risk from invasion by Napoleon Bonaparte. And when a would-be thief, whom Mary has prevented from stealing her father’s mourning rings, turns up dead on the beach, Mary must jeopardize her position at the castle, her relationships, and her family’s name in order to bring the truth to light.

I came up with the idea for this novel in 2013, thought about it for years, started writing it in late 2017, and then in 2019 finished drafting, queried, and found my agent. After all the work I put into it, it was magical to sign the contract.

What’s up next for The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet?

- Working with the art department and marketing department at Tule

- Content edits

- Copy edits

- Proofreading

Meanwhile, I am also working on the second draft of Mary Bennet book 2, in which Mary goes to London and has all sorts of adventures. Onward we go!

2019 in Review: Writing, Writing, and More Writing

I would be remiss if I did not write my annual post about writing in the past year.

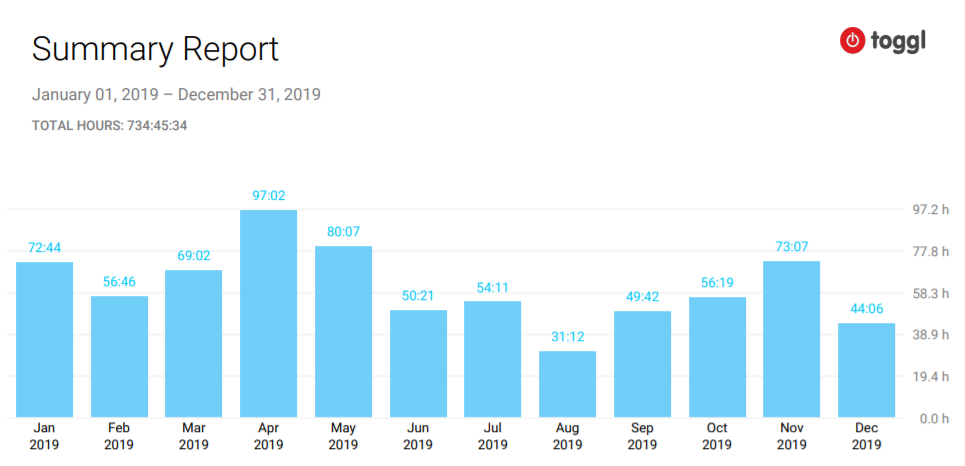

In 2019, I wrote more than I have in any previous year, coming in at 734.45 hours. That averages out to about two hours a day, every single day. (In comparison, last year I wrote 675 hours, which was a personal best; in 2017 I only wrote 400.)

Of course, I didn’t spend two hours writing every single day–there were weeks where I did much more, and weeks where I did much less:

And what did I do with those hours?

First and foremost, I spent 381 hours on my Regency Mystery Novel

- Draft 2: 58 hours (I had started Draft 2 in 2018)

- Draft 3: 108 hours

- Newspaper Research: 18 hours

- Draft 4: 6 hours

- Draft 5: 15 hours

- Draft 6: 77 hours

- Draft 7: 16 hours

- Submitting to Literary Agents: 47.5 hours

- Working on Book 2: 34 hours

- And other minor tasks

The big news of the year was getting a literary agent, something I wrote extensively about in another blog post.

And then the rest of the writing time was a mix of writing/revising short stories, critiquing, conferences, writing groups, running an international writing contest for a literary nonprofit, journal writing, etc. I had one short story published during the year, Paradisiacal Glory

During the year, I wrote a solid 55,000 words, and perhaps a significant amount more (during the revision process I rewrite a lot of entire sentences, paragraphs, and scenes, which sometimes doesn’t end up in my word count log).

Not included in my writing chart, but also writing-related: In August 2019, I started a part time job, working as an adjunct faculty member at Western Michigan University, where I now teach first-year writing.

And that’s my year! For the next year, I plan to finish book 2 in my Regency mystery series, and perhaps start researching a new series.

Revising for a Literary Agent (and How I Got my Agent)

I recently signed with a literary agent, Stephany Evans of Ayesha Pande Literary, and like most agents, she had revision notes for me.

But before I talk about my process of revising for a literary agent, let’s start with a little background. A lot of people ask, “When you start submitting, is your book finished?”

The answer is, your book should be as polished as you can make it with the help of your writing group, beta readers, and critique partners.

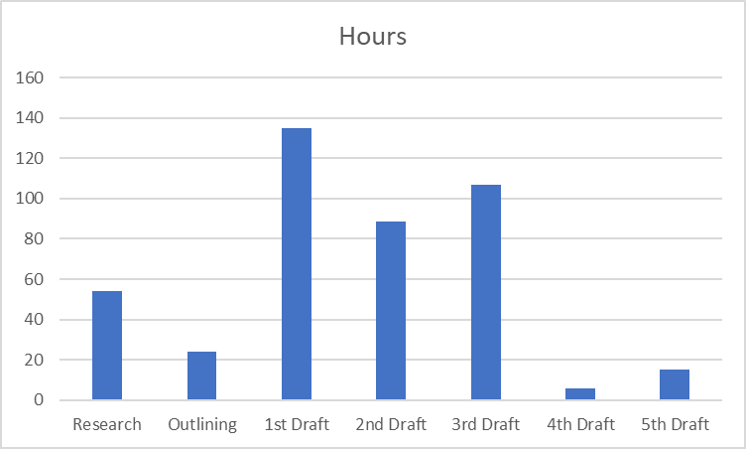

For this book, which we shall call my Regency Mystery novel, I spent 54 hours doing research, 24 hours outlining, and 135 hours on the first draft. (I actual researched, outlined, and wrote the first draft all at the same time, based on what was needed any given week—it wasn’t sequential.)

Then, I did lots of revising: 88.5 hours on the second draft, then I sent it to readers for feedback, 107 hours on the third draft, then I sent it to readers again, who did not have much feedback, and then 6 hours on the fourth draft.

At that point, I felt like my Regency Mystery novel was as ready as I could make it, so I started querying literary agents.

One of these agents requested the beginning of my book, liked it, and asked to read the whole book. I sent it to her. She read it. She rejected it.

However, it was a really helpful rejection letter. It was only one paragraph long, but it included a couple of sentences about what she saw as a structural problem in my book.

I thought about it for a few weeks (I often have to digest feedback before I can figure out how to incorporate it) and then I wrote a fifth draft. Making the structural change to increase tension took about fifteen hours.

Then I started querying again.

Query. Query. Query. Query. Query.

I queried a lot of agents at this point—I was getting requests for partial manuscripts, so I knew my query letter was working, and I was getting requests for full manuscripts, so I knew people liked my opening pages. I had several dream agents that I still hadn’t contacted, and I wanted to make sure that I queried them.

Query. Query. Query. Query. Query.

I queried 51 agents in all.

One of my dream agents, who I hadn’t queried in the first rounds because she wasn’t specifically looking for historical mystery, wrote back and asked for my manuscript. I sent it to her. A week and a half later she emailed me and said was half-way through and loving it. Not long after, she sent another email: she wanted to speak with me on the phone about my book.

And thus, one of the most anticipated moments for a writer:

The Call

(Despite how cool rotary phones look, I don’t know how to use them. I used my cell phone.)

The phone call went like this:

- General pleasantries and conversation. To my utter horror, the call kept dropping.

- We got a good connection established. We decided to skip general pleasantries.

- Stephany Evans told me all the things that she loved about the book. It was a lot of things. I really got the sense that she understood my vision—she loved my premise, my characters, my writing style, the emotion and the themes.

- We talked about revisions.

I had left a number of loose ends in my book that I didn’t realize were there (an important character disappeared and didn’t have a backstory, several characters were never fully tied into the mystery plot, could the boat serve a bigger purpose, to complete this relationship arc this character needs to apologize, etc. etc.). However, there was something much bigger: I was staying on the fringes of the mystery genre. While my novel included all sorts of mystery and sleuthing and discovery, there was no Big Mystery, no Large Problem that occurs near the beginning and then needs to be solved. A Big Mystery could be a dead body, a kidnapped person, a significant theft, etc.

As we talked about this revision, it was like stepping into a Frederick Edwin Church painting: all of a sudden there was a breathtaking vision before me of what my novel could be.

Cotopaxi by Frederic Edwin Church

One of the reasons I was excited was the feedback felt like it was making more the book into more of I wanted it to be, instead of shifting it into something else. (To me, this is a key for revisions, whether you are revising for an agent, an editor, or a critique partner.)

Back to the phone call.

- Stephany Evans asked if I would be willing to make the sort of revisions we had discussed. I said something along the lines of, “Yes! I think adding a subplot would be work really well.” She then asked me about the time frame—how long would it take me to revise? I said about a month, and then I asked if I could revise and resubmit the manuscript to her. (“Revise and resubmit” is a pretty common request in the publishing industry.)

- Stephany said that she actually wasn’t asking me to revise and resubmit—she was confident I would be able to make the revisions, and she wanted to make an offer of representation.

- I said that I was extremely interested and would love to work with her, but that other agents were looking at it. We made a plan to talk in the not so distant future and that afternoon I rapidly contacted everyone else who had the query or the manuscript.

I didn’t end up receiving other offers or representation. But, one of the other agents who read the full manuscript gave me the same big picture feedback—she pointed out the same, Big Mystery plot problem. This was a great confirmation to me that the revisions I was about to start were really on track with what the book needed.

During the time while I was waiting to hear back from the other agents, I did extensive outlining and planning for how to tackle the revision. And then, as soon as I signed a contract with Stephany Evans, I plunged into the revisions.

I spent 77 hours revising over the course of 5 weeks.

Most of the time went to adding the subplot, which required introducing several characters earlier in the book, adding a new character, and writing three and a half new chapters. A lot of the other chapters had new partial or full scenes; other scenes had to be rewritten to reflect the Big Mystery.

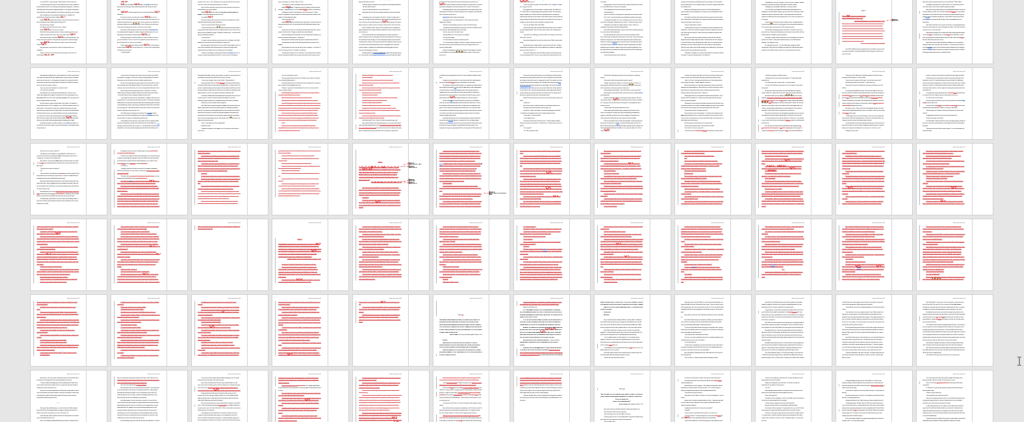

The first hundred pages of the book didn’t change much at all. And then, things started to get colorful.

I used track changes, and so anything I changed, added, or deleted shows up in red. When you look at the book in 10% size it really gives you a sense of what happens when you add a dead body to your book.

My book is now about 15,000 words longer than it was before (sixty pages or so, depending on font and margin size). The great thing was that I was able to solve all of the loose ends by the addition of the subplot—it fixed not only the big problem with my book, but the smaller ones as well.

Over the course of the five weeks, I didn’t just change and add things—I also got feedback from critique partners and my writing groups on every single new scene in the book. It is hard (in my opinion) to make new material match writing that has been through multiple drafts, so I knew I needed eyes on the manuscript.

I only sent the full manuscript to one person, a trusted friend who is an incredible writer (and who also happened to be one of my college roommates). She had never read a single word of the book before, which was useful because she came at the manuscript completely fresh. She knew that I had added a subplot but did not know which one. And when she emailed me after reading the book, she thought it was a different subplot that was new. She was shocked that the new subplot was actually the Big Mystery, because it seemed so essential and interwoven in the story.

And that is the story of how I got my agent, and the revisions I have done for her so far. I love what my book is becoming, and I am excited to see what happens next.