The Hardest Thing in the World

Writing is the hardest thing in the world.

I didn’t think that when I started writing at the age of 5, but I often think that now. Some days, I feel like I’m pulling my toe nails out (don’t spend too much time visualizing it) simply to write 500 words.

My daughter is 6 weeks old, so I’m officially past “maternity leave.” Which means I’m back to the grind on my steampunk novel. Every day I must write at least 500 words. It’s not very much, and once I hit the 500 mark it often gets easier to write another 200 or 400 words. But it’s something I have to force myself to do, to push through on a daily basis. Since I’m at 15,000 words, if I keep it up, I’ll easily be done with this draft by the end of February, and potentially by the end of January.

I much prefer when I have a full draft and I get to revise, even though I know I’ll be rewriting most sentences.

But I should stop stalling. I’ve written 330 words, and have 170 words more to go before I’m allowed to go to bed. I even know what I’m going to write–I just have to buckle down and do it.

Dreams: A Haiku

Lay your dreams in sand

Pretty patterns, bright colors.

Then watch them wash away.

Photo credit: penelopejonze

Living the Dream (of Homemaking and Motherhood)

A few nights ago, I had a very vivid dream which involved me reading a pile of books to my toddler. I mentioned the dream to my friend Shann, and added, “And I’ve read a lot of books to Myra today.”

Without a moment’s hesitation, Shann replied, “You’re living the dream!”

(Photo by Marissa Strniste)

Many visuals and many roles come to mind with the phrase “Living the Dream,” and typically being a mother is not one of them. You might picture a tropical island, fame, riches, or a relaxing lifestyle. Or, like in the song from the film Tangled, achieving a lofty goal (becoming a concert pianist, collecting ceramic unicorns, crafting a fulfilling career in interior design, or traveling outside of the limits of your current experience).

Recently, several of my high school friends have become very successful in the business world. It’s led me to consider the question, “What would I do if I had millions of dollars?”

For one, I’d buy all the expensive, foreign cheeses I wanted, and we could afford to go on more dates. I’d also raise my book budget, which is currently capped at $10 a month. Oh yes, and I’d buy a house. With a lawn mower.

But besides overflowing bookshelves and fridges, how would my life really look different? How would I choose to spend my time?

(Photo by Oberazzi)

After much thought I’ve decided that I would still choose to be a homemaker.

Yes, that means 60+ hours a week changing dirty diapers, cooking meals that will appeal to both adults and toddlers, taping broken objects, and trying to keep the house from descending into chaos. And when my next child is born, that will include spending hours every day breastfeeding and a fair number of sleepless nights.

But those 60+ hours a week also include my daughter bringing me a book, climbing onto my lap, and listening as I tell her stories. It includes singing the alphabet with Myra, taking her on walks, teaching her to enjoy the pool, and playing tickle attack.

It includes precious little moments that happen all the time, if only I choose to notice them. For example, yesterday I found my daughter sitting in the bathtub, fully clothed, waiting for the water to come out. (She had already taken one bath, but was pointing at the faucet saying, “water, water.”)

Another precious moment: my daughter stuck in a cupboard, saying, “Mom. Mom. Mom!”

Am I living the dream?

It’s not the dream I had in high school, that’s for sure. (My answer my senior year when I received the question, “Where will you be in 10 years?” did not include children.)

And it’s still not my only dream.

I have a lot of dreams, from being a published author to becoming accomplished at Chinese calligraphy to designing crochet patterns.

I haven’t touched my bamboo brushes in years–I never have two uninterrupted hours, and toxic paints plus children are a bad combination. I spend time writing, but it’s bits and pieces of free time here and there. I slowly create projects with my yarn, but I still haven’t figured out how to visualize something without a pattern.

These dreams, like many of the other dreams I cherish and love, have been mostly put aside, because of another dream I’m choosing to work on.

I choose to be a homemaker, because I feel it is best for my children, especially in their early years, to have someone to teach them and guide them and take care of them on a constant basis. And while it would make a big difference to our finances and budget if we had two incomes, I’m lucky enough not to have to work.

Right now, being a mother and a homemaker is my most important dream. And like all dreams that are really worthwhile, it requires sacrifices. This year, I’ve struggled with a lot of the sacrifices I’ve had to make. But it’s worth it, because right now I’m living the dream.

(For a related post, see Guardians of the Hearth.)

Brigadeiros Recipe (A Brazilian Chocolate)

Last night I made brigadeiros, that yummy Brazilian chocolate that makes Brazil lovers drool. These were probably one of my top five favorite foods (yes, chocolate is a food) when I lived in Brazil. My picture seemed to garner a lot of love on Facebook, and a bit of lust, so I thought, if I can’t share the chocolates with my friends (I’m not sure how I feel about sharing chocolates) then I can at least share the recipe.

Here’s the recipe I used–I translated it from Portuguese about 7 years ago, and don’t remember where I got it from.

Brigadeiros (A Brazilian Chocolate)

1 can of sweetened condensed milk

3-4 tablespoons of cocoa

Several tablespoons butter

Chocolate sprinkles (use real milk chocolate sprinkles)

Melt the butter on the stove. Mix in the cocoa. Add the sweetened condensed milk. Stir, over heat, as you bring the mixture to a low boil. Keep stirring until the consistency changes and it becomes thick and sticky. Remove from heat. Let cool enough so you can touch it with your fingers, but no cooler. Put butter on your fingers, and quickly roll the mixture into balls (of about and inch to an inch and a half diameter). Roll the balls in chocolate sprinkles and place them in candy cups (like miniature muffin cups). Let cool before eating.

Makes about 30.

More tricks, techniques, and pictures:

Chocolate Sprinkles

The key to this recipe is to use real chocolate sprinkles. If you go to a normal grocery store in the US and look really carefully at the label, you’ll realize that what you’re buying is not chocolate, but chocolate flavored. Alright–okay for some things, but not ideal for brigadeiros.

My sister got me these real chocolate sprinkles from Germany–they’re 32%, which is way more than your Hershey’s bar will have.

You can also order them online, or get them at a specialty store: Pirate O’s in Draper, UT has them, as do other gourmet and foreign food stores.

Candy Cups

It’s also helpful to actually have candy cups. They’re a little smaller than mini muffin holders. See the comparison:

I bought these at a cake shop. You could use mini muffin paper cups and it’d be just fine, the risk is that you’ll make them too large, and you’ll be overwhelmed by chocolately goodness. (Okay, maybe that’s not a bad thing.)

More Pictures

Who can resist a brigadeiro close-up?

And my Brazilian doll, hoarding several brigadeiros, which are as large as her head:

Guardians of the Hearth

For an LDS woman, being a “guardian of the hearth” is about much more than cooking food on a fire (or on the stove)–it’s about the entire spiritual responsibilities and divine roles of women in the home.

(Frederick Childe Hassam’s “The Fireplace”)

This month’s visiting teaching message is titled “Guardians of the Hearth,” quoting President Gordon B. Hinckley, who said the following in a 1995 address to women:

You are the guardians of the hearth. You are the bearers of the children. You are they who nurture them and establish within them the habits of their lives. No other work reaches so close to divinity as does the nurturing of the sons and daughters of God.

It’s insightful to read this quote in the context of the woman and her relationship with the historic hearth. Recently, I’ve been reading the book Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light. The educational yet entertaining book spends most of its pages talking about the development of electricity and how it changed Western culture and society, but the first quarter of the book is about what life was like before electric light.

(Photo of tenant farmer and family in front of fireplace taken as part of the FSA project in 1939.)

The hearth–the fire–was often the figurative center of the home. It was used for cooking and the heat for ironing. In the evening, candles and lamps were often used sparingly, because of their expense, so the hearth was often the main source of light. It heated the home–or at least the portion of it closest to the fire. Without the other evening diversions and entertainments made possible by electric lights, families congregated in the evening around the hearth–it was a place of warmth and a place for stories and for the shared weaving of lives.

I don’t have a fireplace in my home, but I still can be the guardian of the hearth. I can be a guardian of light, of time spent together as a family, of warmth, of safety, of food, of shared stories. As a wife and mother, I am not the only one with responsibilities for the hearth–others often light and tend to our home’s fire. But I am the guardian–a guard and protector of light and spirit, one who preserves the fire and makes sure its embers do not go out.

(Helen Allingham’s “In the Nursery”)

Sarah Jane Adams: A Love Story

I love family stories. They’re so interesting and compelling. For Valentine’s Day I wanted to publish a tale of love.

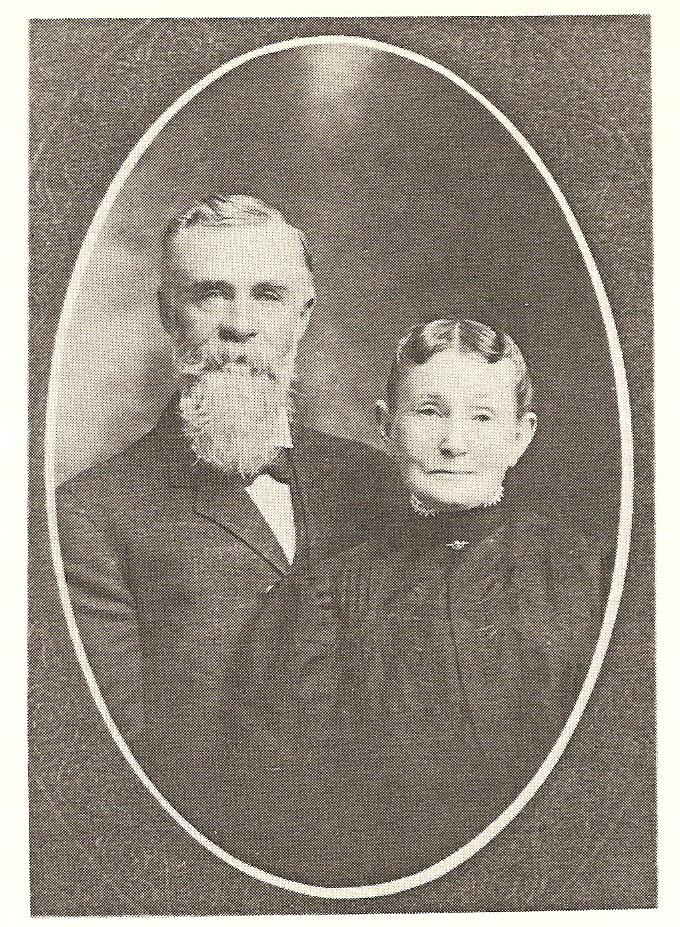

Robert Pemberton and Sarah Jane Adams

Here’s the story of one of my ancestors, Sarah Jane Adams, as told by another descendant, Bertram Adams (in the book The House of Benjamin: Ancestors and Descendants of Benjamin Adams of Boaz, 1980).

Sarah Jane Adams[,] the auburn-haired daughter of Hannah Rhinehart and her husband Benjamin Adams[,] was born 18 Oct. 1847 in Grant county, Indiana, and there grew to womanhood. On a Saturday, 25 Aug. 1866, three couples gathered in front of their school mates and friends to be married in one ceremony on the long porch of the home of Isaiah Pemberton at Back Creek, near Jonesobro, Grant co., by Alfred C. Barnard, J.P. (MC)

Robert Pemberton to Sarah Jane Adams

Charles Baldwin to Melinda Newby

Axum Newby to Hannah Pemberton

Within ten days after they were married, the three couples started their 500 mile journey to Iowa, in five covered wagons loaded with all their possessions. The young brides all cut their hair and wore bloomer suits for convenience in traveling, in spite of numerous unfavorable comments. No incidents of the 23 days of travel to Hartland, Iowa have been recorded, except for some rainy days at the beginning.

Hartland, in Marshall co. Iowa, was a Quaker community, and some of the Quaker Pembertons had already settled in that vicinity. Since Robert and Sarah Jane had been married out of the Quaker Church, the Quakers objected and were about to “church” Robert, but his wife quietly converted and all was peace. She remained a staunch and faithful member until the end of her days. (141)

I love that Sarah Jane had auburn hair. Apparently, she was also a “small woman, not over five feet tow inches tall and quite slender; she had light complexion with blue or grey eyes; there was no silver in her curly dark auburn hair until shortly before her death.” Her husband “was a tall bearded man and some said he much resembled General Robert E. Lee” (142).

Sarah and Robert had 9 children; their first and third children died as infants.

(Their 9 children, in birth order, were Orilla, Tacy Jane, William R. (or H), Charles Benjamin, Perle C., Jeannette, Delbert H., Myrtella, and Wynn Robert. I have no idea who is who in the picture.)

Sarah Jane Adams Pemberton was a widow for the last 28 years of her life. She lived in West Los Angeles: 11567 Santa Monica Boulevard. At her death, on February 19, 1940, she was 92 years old.

When I get the chance, I’ll upload a copy of a note that she wrote, with her signature.

Cutting off your hair and wearing bloomers to move across the country, making sacrifices to make things work, having 9 children and living faithfully together for your entire lives–if that’s not love, I don’t know what is.