Big Mary Bennet Energy: 2022, A Year in Review

And now, as we reach the final day of 2022, it is time for my annual writing year in review.

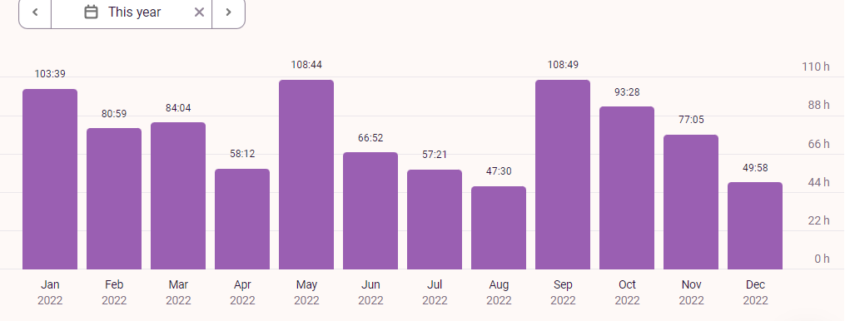

I spent 937 hours writing in 2022, and my year looks like a series of waves.

Due to a variety of outside factors, my writing time varied from 47 to 109 hours each month, but it did so in an aesthetically pleasing way, which is definitely a win.

(Note: 937 hours is less time than I spent writing in 2021, when I wrote for 1000 hours, but more than I spent writing in any previous year.)

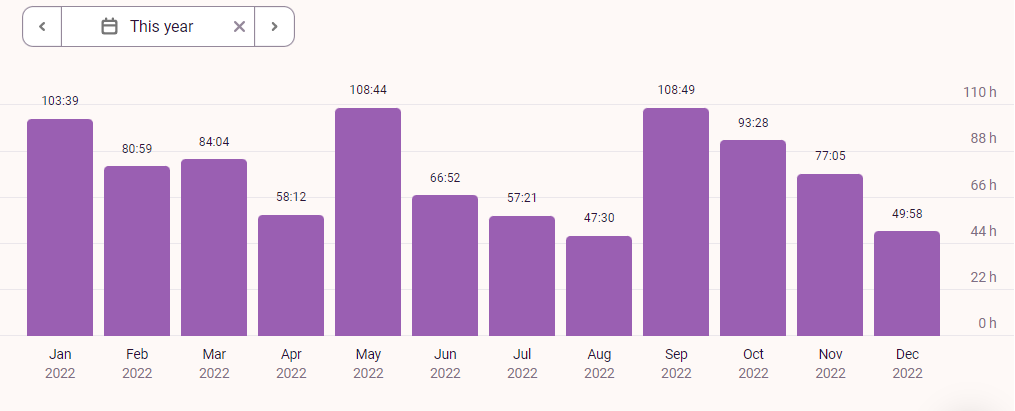

Which leads us to the next chart: how did I spend my time?

This year had big Mary Bennet energy, and that determined a lot of my writing hours. True, I only spent 32 hours doing final revisions on my third Mary Bennet novel. But the second and third books in the Mary Bennet spy series were both released:

The True Confessions of a London Spy in March 2022

The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception in September 2022

I had my launch party for The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception at This is a Bookstore/Bookbug in Kalamazoo, MI.

It was exciting to have these books released in close proximity, because then readers could enjoy the full story arc without having to wait very long. As you’d expect, two book releases takes up a lot of time, and I spent 309 hours on everything from my website to guest blog posts to presentations to marketing tasks.

This year was also thrilling for the first book in the series, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, which had several award wins and nominations:

-Winner of the LDSPMA Praiseworthy Award for Best Suspense/Mystery novel

-One of five nominees for the Mary Higgins Clark Award

At the Edgar Awards: me with three of the other finalists for the Mary Higgins Clark Award

-One of five finalists for the Whitney Award for Best Mystery/Suspense novel

The Big Question: Will we see more of Mary Bennet?

I have had so many readers finish the third book and ask, “Will we see more of Mary Bennet?” Others have asked if I will write a Kitty Bennet series.

The series was originally conceived as a trilogy. I wanted it to feel complete and have a satisfying resolution for Mary (and company) by the end of the third book.

However, there are other stories that I would love to tell about Mary and her sisters. So I think it’s fair to say that there will very likely be more books in Mary and/or Kitty’s futures.

That said, I have been working on this series non-stop from 2017 to 2022. Five full years. That’s a lot of time to spend in one story world, with one set of characters. A book takes me at least a year or two to write, and it’s very all-consuming. So I decided that the time had come to work on a brand new murder mystery.

The New Murder Mystery:

I’m still keeping this largely under wraps, but I will say that my new murder mystery is set in Paris in the late 1800s, with a number of fascinating historical figures. The main character of the book is a determined woman in her thirties trying to make her way in the world. But then there is a theft and a murder, and she is drawn into solving the mystery.

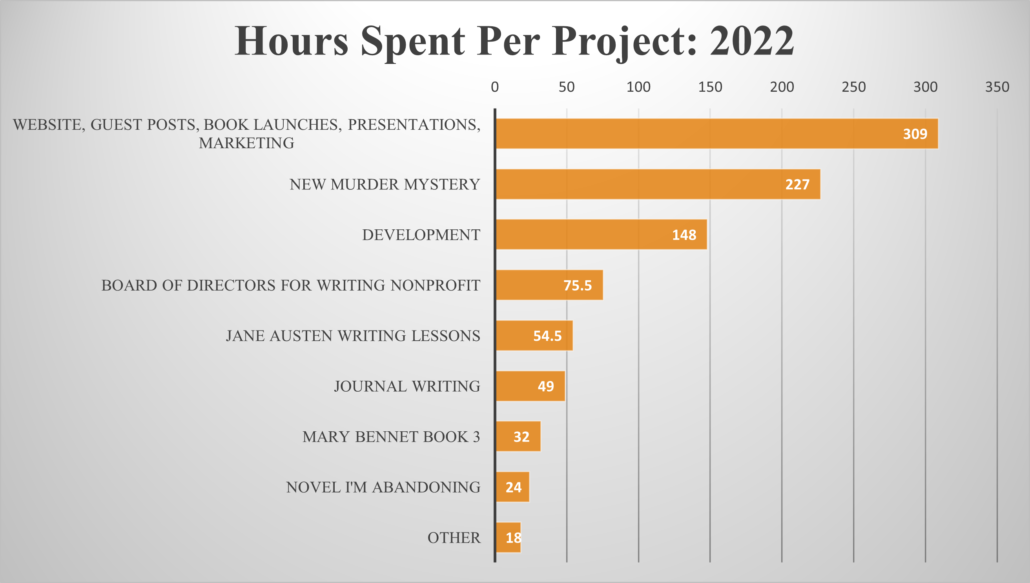

I spent 227 hours on this book in 2022. While I had to do a lot of research for the Mary Bennet novels, I already had a strong background on Jane Austen and Regency England. I did not have that same background for my new murder mystery, so I’ve had to do a lot of additional research on everything from politics to architecture. Fortunately, I love research. One thing I didn’t count towards writing time was studying French. I’m fluent in Portuguese, and reading Portuguese definitely helps with reading French, but knew I needed to study French itself to help me read some of the sources (including newspapers and a few biographies) that are only available in French.

A few of the research books I’ve read for my current novel

While I love research, one cannot research forever. One of the things that I am most happy about for this year is that I found my main character’s voice, I found my narrator voice, and I found the voices of many of my other characters.

I’m now at the 60% mark on the first draft. In the new year, I plan to finish the first draft and then revise, revise, revise.

What Else Counted as Writing:

There are endless other things that counted as writing this year, but here’s a few of note:

-Choosing out formal gowns. I rented dresses for both the Edgar Awards and the Whitney Awards, and I definitely counted the dress search as writing time. (Under my Development category, which includes all writing and career development.)

My dress for the Whitney Awards. Both my dress for the Edgars and the Whitneys were from Rent the Runway.

-I ran a successful Kickstarter for a writing nonprofit and helped publish an anthology.

-I abandoned a novel. I went back and began another revision on an old mystery novel I wrote in the mid-2010s. And then I decided it’s not the right book, so I am officially abandoning it. We’re all better off.

-I wrote 17 new Jane Austen Writing Lessons, focusing on what Jane Austen can teach us about writing dialogue and writing emotions.

-I worked on a few short stories. And I had two short stories published, both with a bit of a religious bent: “The Gift of Undoing” in Saints, Spells, and Spaceships, and the darkest story I’ve ever written, “Burdens,” in Irreantum.

My Writing Plans for 2023:

I have a number of goals, including setting up bookstore and library visits (note: if you’re a bookseller or librarian, I am available for both in-person and virtual visits).

Mostly though, I’m going to buckle down and write, so you can read more of my short stories and novels in the future.

#65: Different Character Approaches to Dealing With and Expressing Emotions

Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility focuses on two sisters, Elinor and Marianne, who act as foils to each other. They see the world differently; they treat relationships differently; Elinor places more value on reason while Marianne places more value on feelings and sensibility. One of the most stark contrasts between the two sisters is how they deal with their emotions and how they express them to others.

Elinor and Marianne, as depicted in the 1995 film version of Sense and Sensibility

Both Elinor and Marianne experience similar loss: they are both separated from and hurt by the men they love.

When Willoughby leaves Marianne, she has a very dramatic response, and suffers “violent affliction.” Her emotions become less violent, but they continue to be marked by outward pining and despair. She becomes very inwardly focused, not noticing the needs or circumstances of those around her, and she makes a scene at a London ball when she sees Willoughby. After he marries someone else, goes out in bad weather and becomes deathly ill.

When Elinor discovers that Edward Ferrars is secretly engaged to Lucy Steele (through Lucy confiding in her), she suffers intense pain, but she refuses to outwardly show it to Lucy. And then she continues to mask her emotions with her family, even though doing so pains her. She knows that Marianne is suffering, and she doesn’t want to add any more burdens to her family by sharing her own suffering; furthermore, she is bound by a promise she has made to Lucy Steele, and because of that promise she does not know how to share her pain with those closest to her. Yet because she is a point of view character, as readers we see and understand her suffering and her internal angst.

Elinor and Marianne, as depicted in the 2008 Sense and Sensibility miniseries

These two characters react to similar situations differently because of their contrasting personalities and because of different outside circumstances. In addition to considering how the same character will express small, medium, and large emotions differently, writers should consider how different characters deal with and express their emotions.

Later, when it becomes public knowledge that Edward is engaged to Lucy Steele, Marianne is in complete shock. But she notices that her sister is not surprised.

“How long has this been known to you, Elinor? has he written to you?”

“I have known it these four months. When Lucy first came to Barton Park last November, she told me in confidence of her engagement.”

At these words, Marianne’s eyes expressed the astonishment which her lips could not utter. After a pause of wonder, she exclaimed—

“Four months!—Have you known of this four months?”

Elinor confirmed it.

“What! while attending me in all my misery, has this been on your heart? And I have reproached you for being happy!”

“It was not fit that you should then know how much I was the reverse!”

“Four months!” cried Marianne again. “So calm! so cheerful! How have you been supported?”

Marianne struggles to understand how Elinor’s outward reality could be in such contrast to her inward reality, because for Marianne, her inward and outward realities are typically aligned.

To Marianne’s question, Elinor responds:

“By feeling that I was doing my duty.—My promise to Lucy, obliged me to be secret. I owed it to her, therefore, to avoid giving any hint of the truth; and I owed it to my family and friends, not to create in them a solicitude about me, which it could not be in my power to satisfy.”

Marianne seemed much struck.

“I have very often wished to undeceive yourself and my mother,” added Elinor; “and once or twice I have attempted it;—but without betraying my trust, I never could have convinced you.”

“Four months! and yet you loved him!”

“Yes. But I did not love only him; and while the comfort of others was dear to me, I was glad to spare them from knowing how much I felt. Now, I can think and speak of it with little emotion. I would not have you suffer on my account; for I assure you I no longer suffer materially myself. I have many things to support me. I am not conscious of having provoked the disappointment by any imprudence of my own, I have borne it as much as possible without spreading it farther.”

Elinor goes on to tell Marianne how she has forgiven Edward and does not blame him. Then she says:

“Edward will marry Lucy; he will marry a woman superior in person and understanding to half her sex; and time and habit will teach him to forget that he ever thought another superior to her.”

Marianne cannot accept that her sister could reach such a point if she truly and fully loved Edward:

“If such is your way of thinking,” said Marianne, “if the loss of what is most valued is so easily to be made up by something else, your resolution, your self-command, are, perhaps, a little less to be wondered at.—They are brought more within my comprehension.”

But Elinor will not accept Marianne’s judgment. She rebukes Marianne, in essence saying that she has loved and felt as deeply as Marianne:

“I understand you. You do not suppose that I have ever felt much. For four months, Marianne, I have had all this hanging on my mind, without being at liberty to speak of it to a single creature; knowing that it would make you and my mother most unhappy whenever it were explained to you, yet unable to prepare you for it in the least. It was told me,—it was in a manner forced on me by the very person herself, whose prior engagement ruined all my prospects; and told me, as I thought, with triumph. This person’s suspicions, therefore, I have had to oppose, by endeavouring to appear indifferent where I have been most deeply interested; and it has not been only once; I have had her hopes and exultation to listen to again and again. I have known myself to be divided from Edward for ever, without hearing one circumstance that could make me less desire the connection. Nothing has proved him unworthy; nor has anything declared him indifferent to me. I have had to contend against the unkindness of his sister, and the insolence of his mother; and have suffered the punishment of an attachment, without enjoying its advantages. And all this has been going on at a time, when, as you know too well, it has not been my only unhappiness. If you can think me capable of ever feeling, surely you may suppose that I have suffered now. The composure of mind with which I have brought myself at present to consider the matter, the consolation that I have been willing to admit, have been the effect of constant and painful exertion; they did not spring up of themselves; they did not occur to relieve my spirits at first. No, Marianne. Then, if I had not been bound to silence, perhaps nothing could have kept me entirely—not even what I owed to my dearest friends—from openly showing that I was very unhappy.”

Marianne was quite subdued.

“Oh! Elinor,” she cried, “you have made me hate myself for ever.—How barbarous have I been to you!—you, who have been my only comfort, who have borne with me in all my misery, who have seemed to be only suffering for me!—Is this my gratitude?—Is this the only return I can make you?—Because your merit cries out upon myself, I have been trying to do it away.”

This is a powerful scene between the two sisters, in part because their different approaches to dealing with and expressing emotions requires them to reconcile with each other.

When writing character emotions, it’s important to remember that there is a full range of ways a character can react to the same event: a more dramatic, outward expression or a quieter, more internal expression could both be used for either large or small emotions. A more “emotional” character, like Marianne, does not actually have more emotions—they simply express them in a different manner. It is important to note, however, that the way a character chooses to express their emotions does have consequences: Marianne pining for months does have negative effects on her well-being, and prevents her from dealing with her emotions and facing the truth about Willoughby.

There are a full range of possibilities responses in between these two opposite approaches: there are endless ways a character might deal with or express their emotions. There is no guide, no rule on whether your character should express emotions in a big or small manner, an internal or an external way: this is something you have to choose for each character, and this choice will reveal a lot about the individual and their circumstances.

Exercise 1: Write a scene with two characters. They can be siblings, friends, coworkers, or have something else that ties them together and creates similarities between them. In the scene, have something negative happen to both of the characters. The two characters should deal with and express their emotions in different ways (they do not need to be polarly opposite in their reactions, but they can be).

Exercise 2: Write a second scene with two characters with something in common—they can be the same characters from exercise 1, or new characters. In this scene, have something positive happen to both of the characters. Once again, have the characters deal with and express their emotions in different ways.

Exercise 3: Choose a handful of people in your life that you know well or interact with on a regular basis. For each person, write a several sentence sketch about how they deal with and express their emotions.

Then reflect on the differences between these people, and how their reactions are impacted by their personalities and circumstances.

The Original Title for The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception

I told this story at my launch party in Kalamazoo, Michigan, but I wanted to share it here. The original, working title for The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception was The Lady’s Guide to the Art of War.

In late 2019, my agent Stephany Evans was preparing submission materials for the first book in the series, The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet. Now, when you are pitching a book, even if you would like it to be the first book in a series, you often say, “It’s a standalone novel with series potential.” Publishers sometimes just want one book, and you want them to be interested in the book without them feeling like the book is incomplete and requires a series. And indeed, the first book does stand on its own. But “series potential” means you have further books in mind. In case a publisher was interested in the sequels, Stephany asked me to create a several sentence pitch—with a title—for books 2 and 3.

I had already written a first draft for the second book, which made it much easier to settle on possible titles. After a bit of brainstorming, I ended up settling with The True Confessions of a London Spy, which ultimately ended up being the final title for the book.

Book three was trickier. I knew that it would be set in Brussels. I knew that the book would include Napoleon Bonaparte and the hundred days from when he escaped the Isle of Elba and was defeated one final time. I also knew the book would include a romance, and feature Mary’s sister Lydia. I had enough that I could write a pitch. One of the themes that I knew would be present in the book was war—how war impacts individuals and communities. War is played out not just on the battlefield, but in smaller interactions with huge consequences. And so I came up with the title, The Lady’s Guide to the Art of War.

I have a history with the book The Art of War. We had a copy in my house growing up, and we would discuss Sun Tzu and other military theorists at the dinner table or after watching movies. I got engaged to my husband, Scott, a few weeks before Christmas, and for Christmas that year, my dad gave Scott a beautiful knife from Spain and a copy of The Art of War. Which from my dad is a very excited “Welcome to the family!”

When I got to writing the book, I didn’t draw upon The Art of War as heavily as I thought I would. Its influence is definitely in the book, and Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington likely owned copies and would’ve been quite familiar with it. Mary and Mr. Withrow do discuss The Art of War in one scene, but I realized that it wasn’t quite the right title for the overall themes and focus.

So it was back to the drawing board. I spent hours brainstorming other titles, and after some really useful thoughts and perspectives from my editor, I settled on The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception. What I loved about the title is it captures what Mary must face—deception on the part of others, and the deception she must use in order to unravel the mystery and deal with death. I sent the title in, it was approved by the publisher, and it became the final title for the book.

The book is dedicated to my dad, and despite not including The Art of War in the title, it has a lot of his influence. He helped me choreograph every single action scene in the entire series. I would video call him and say, “I need these things to happen, without these things happening, and this is who the characters are and their skills and strengths,” and he would help me figure it out. After I wrote the scenes, I would send them to him for further feedback.

Titles tend to either come to me easily or they are really difficult and take a lot of work. There is no in-between. But I have been really happy with all my titles so far, and hopefully that’s the case in the future!

#64: The Size or Degree of Character Emotions

When we talk about emotions in writing, we often think of big emotions, when characters are very emotional and emotive.

Yet characters experience not only a broad range of types of emotions, but a broad range of sizes of emotions. Characters have emotions that are strong or overwhelming, but they also have emotions that are fleeting and less consequential.

When considering the size of the emotion, it’s useful to ask:

- To what degree does your character experience this emotion?

- How important is this emotion to the story?

- How many emotional clues need to be planted to convey this emotion?

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth experiences emotions in every scene—and in most scenes, she experiences more than one emotion. Let’s look at how Jane Austen conveys small emotions, mid-size emotions, and large emotions for this character.

Small Emotions

Small emotions are ones that the character experiences either for a short time, or only to a small degree. This might a small annoyance, a temporary flush of joy, a reaction to another character or something that happened.

While attending the Meryton Assembly, Elizabeth overhears Mr. Bingley trying to convince Mr. Darcy to dance, and Bingley points out that Elizabeth could be a good partner. Mr. Darcy replies:

“She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.”

1894 illustration from Pride and Prejudice by Hugh Thomson, via Lilly Library, Indiana University, Wikipedia Commons

While this is a rather weighty insult, Elizabeth has only a small emotional response:

Mr. Darcy walked off; and Elizabeth remained with no very cordial feelings towards him. She told the story however with great spirit among her friends; for she had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in any thing ridiculous.

Clearly she’s not happy with Darcy, but rather than wallowing in the emotion, she sees it as ridiculous and tells it as a funny story.

Throughout Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth often uses humor as a lens to deal with small emotions. For some character, this event could create a much larger emotional response, but for Elizabeth it remains small, and she moves on.

It is a key emotional moment for the reader–one of the most memorable moments in the novel, that sets up their antagonism–but it doesn’t require very much space on the page.

At other times emotions are implied or are barely brushed upon. It’s important for the reader to understand what the character’s emotion is, but it’s a small emotion that needs only a small amount of space.

For example, after Mr. Collins’ arrival, he starts showering compliments on the family:

He had not been long seated before he complimented Mrs. Bennet on having so fine a family of daughters, said he had heard much of their beauty, but that, in this instance, fame had fallen short of the truth; and added, that the did not doubt her seeing them all in due time well disposed of in marriage.

And then, Austen gives us the emotional response of Elizabeth and her sisters, in contrast to Mrs. Bennet’s response:

This gallantry was not much to the taste of some of his hearers, but Mrs. Bennet, who quarrelled with no compliments, answered most readily.

It’s a simple phrase—“not much to the taste of some of his hearers”—but it does all that is needed to do to establish Elizabeth’s sentiments towards her cousin.

1894 illustration by Hugh Thomson from Pride and Prejudice. Jane, of course, is “Not for Sale,” but Mr. Collins is welcome (according to Mrs. Bennet) to choose any of the other daughters. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Mid-Size Emotions

Mid-size emotions are ones that are larger for the character. They occupy more of the character’s heart and mind—they linger, have consequence, or are not as quickly resolved. They have a weightier impact on the character, and they often require more sentences on the page—more emotional clues.

In Pride and Prejudice, after Elizabeth and her sisters meet Mr. Wickham, Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy see them—and Mr. Darcy sees Mr. Wickham. Elizabeth witnesses their emotions, and has her own emotions (particularly her curiosity) piqued.

[Mr. Darcy’s eyes] were suddenly arrested by the sight of the stranger, and Elizabeth happening to see the countenance of both as they looked at each other, was all astonishment at the effect of the meeting. Both changed colour, one looked white, the other red. Mr. Wickham, after a few moments, touched his hat—a salutation which Mr. Darcy just deigned to return. What could be the meaning of it? It was impossible to imagine; it was impossible not to long to know.

Here, Elizabeth notes the interaction, and her questions and her longing to know show her curiosity.

Later on in the scene, we read:

As they walked home, Elizabeth related to Jane what she had seen pass between the two gentlemen; but though Jane would have defended either or both, had they appeared to be in the wrong, she could no more explain such behaviour than her sister.

Elizabeth comes back to her emotion, she comes back to her puzzlement and her curiosity by raising it with Jane.

Mid-size emotions often need either more emotional clues, or recur again at some point in the scene.

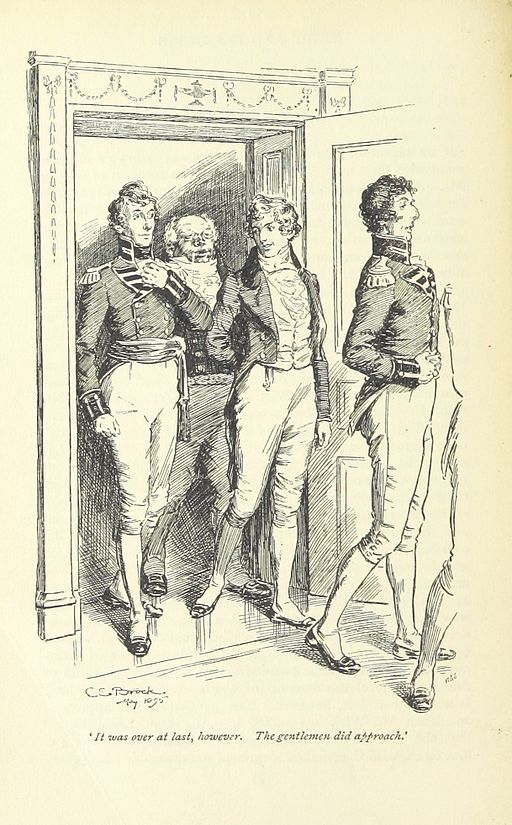

1895 illustration by C.E. Brock of the arrival of Mr. Wickham and other officers at a gathering held by the Phillips family. Via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s not long after this point when Mr. Wickham’s confides in Elizabeth, telling his story of how he has been wronged by Mr. Darcy. This revelation produces emotions in Elizabeth that are larger than the emotions she felt upon seeing their initial antagonism, but still mid-sized in comparison to some of her emotions in other scenes.

Elizabeth is shocked, and we see this shock and surprise in her speech:

“This is quite shocking!—He deserves to be publicly disgraced.”

In the scene that follows she then asks follow-up questions. She pauses when speaking. She reflects. She remembers things Mr. Darcy has said in the past that would seem to corroborate Wickham’s claims. These emotional clues are layered on each other, giving a sense of how she feels.

She also uses many more exclamation marks than in her normal dialogue, and uses strong word choice:

“How strange!” cried Elizabeth. “How abominable! I wonder that the very pride of this Mr. Darcy has not made him just to you! If from no better motive, that he should not have been too proud to be dishonest—for dishonesty I must call it.”

Even once her conversation with Mr. Wickham is over, she keeps returning to it in her mind. Her emotions on the matter, and on Mr. Wickham more generally, become her entire focus:

There could be no conversation in the noise of Mrs. Phillips’s supper party, but his manners recommended him to everybody. Whatever he said, was said well; and whatever he did, done gracefully. Elizabeth went away with her head full of him. She could think of nothing but of Mr. Wickham, and of what he had told her, all the way home; but there was not time for her even to mention his name as they went, for neither Lydia nor Mr. Collins were once silent.

And her emotions don’t end in this scene. The next chapter begins:

Elizabeth related to Jane the next day, what had passed between Mr. Wickham and herself.

Note how much more page time is given to this emotion than to when Mr. Darcy insulted her at the ball. Note how much more it consumes her—how it engages her in different ways and uses a larger variety of emotional clues.

Large Emotions

Large emotions are bigger for the characters. They are often more personal and have larger consequences. They can accompany events or knowledge which is life changing or life shattering. Often these emotions are large because the circumstances require the character to develop a new understanding of the world and their place in it.

Like with mid-size emotions, large emotions require more page time, a layering of emotional clues, and a return, multiple times, to the emotion. Large emotions also provoke stronger reactions, stronger or more extreme physical sensations, and lead the character to engage in behavior that is outside of their norm.

1894 illustration by Hugh Thomson of Colonel Fitzwilliam and Elizabeth. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Elizabeth is extremely upset when she finds out from Colonel Fitzwilliam that it was Mr. Darcy who broke up Mr. Bingley and her sister Jane. He says simply,

“There were some strong objections against the lady.”

Paragraphs follow in which Elizabeth deals with her emotions, thinking about what happened. She considers how in some ways Mr. Darcy is right to have objections, but then she counters her own thoughts by thinking about how much Jane has been wronged.

The agitation and tears which the subject occasioned, brought on a headache; and it grew so much worse towards the evening that, added to her unwillingness to see Mr. Darcy, it determined her not to attend her cousins to Rosings, where they were engaged to drink tea.

For most of her smaller negative emotions, Elizabeth has used humor. For mid-sized ones, she grapples with the problem, considering it from many sides—which she also does here. But this is emotion to a new degree. This has caused tears and a headache. And while Elizabeth is normally very correct in her behaviors and social expectations, she does not go to Rosings as she normally would.

In the next chapter we see the continuation of this emotion as she goes through all of Jane’s letters, trying to read Jane’s emotions and see how Mr. Bingley’s absence has impacted her sister.

It’s only a few pages later that Mr. Darcy proposes to her. She angrily turns him down, expressing her emotions to him in multiple ways. Even after he has gone, we continue to experience her emotions with her, and we have a longer shift into free indirect speech than we’ve experienced at other points in the novel.

The tumult of her mind, was now painfully great. She knew not how to support herself, and from actual weakness sat down and cried for half-an-hour. Her astonishment, as she reflected on what had passed, was increased by every review of it. That she should receive an offer of marriage from Mr. Darcy! That he should have been in love with her for so many months! So much in love as to wish to marry her in spite of all the objections which had made him prevent his friend’s marrying her sister, and which must appear at least with equal force in his own case—was almost incredible! It was gratifying to have inspired unconsciously so strong an affection. But his pride, his abominable pride—his shameless avowal of what he had done with respect to Jane—his unpardonable assurance in acknowledging, though he could not justify it, and the unfeeling manner in which he had mentioned Mr. Wickham, his cruelty towards whom he had not attempted to deny, soon overcame the pity which the consideration of his attachment had for a moment excited.

She continued in very agitated reflections till the sound of Lady Catherine’s carriage made her feel how unequal she was to encounter Charlotte’s observation, and hurried her away to her room.

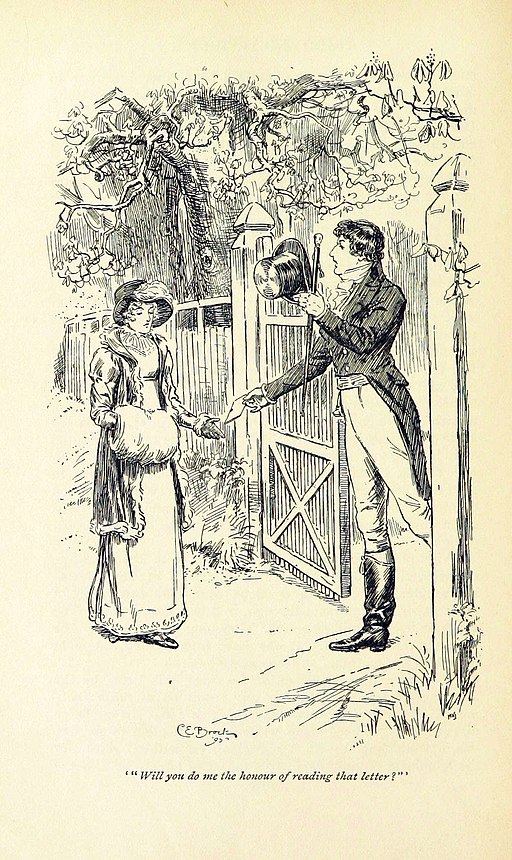

1895 illustration by C.E. Brock of Mr. Darcy giving Elizabeth a letter. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Later, she receives his letter full of explanations. During the letter, we just read it with Elizabeth–the whole letter is included with no interruptions, no character actions or thoughts. We experience our own emotions as readers, and can guess at Elizabeth’s. Then after the letter, we have lengthy passages in which she walks, she re-reads, she analyzes specific phrases, she reflects. Her emotions undergo multiple shifts—and we go with her through these shifts.

Large emotions are often more complicated. They are not as clear cut—anger, joy, frustration, forgiveness can all be complicated and filled with nuance. Large emotions are bottles filled to bursting, and often require the character’s exploration and the narrator’s. They shift, they grow, they lessen, they increase again, and as we ride this roller coaster with the character, we empathize and at times even have a cathartic experience.

Conclusion

If you attend a symphony, you will not hear all the instruments playing at full volume the entire time. That would not be good music. Instead, some movements may be performed at quietly, while others will swell to fortissimo, some sections may highlight the violins, while others may feature brass instruments, and other still use a solo. We may only hear the cymbal a handful of times, but when we do, it will be at key moments.

We should do the same when we write character emotions: include a range of emotions, some of which are focused on at different times. Sometimes we touch on an emotion for only a moment; other times we explore the emotion for an extended period, or bring back an emotional theme later in the story. Including varying degrees of emotions—small, mid-sized, and large—creates contrast and emphasis, directs the readers’ attention, and serves to better illustrate character, as we see how they react and change in moments big and small.

Exercise 1: Emotion chart

Reread a book or rewatch a film you enjoy. As you do so, create a chart of character emotions. You can focus on the main character’s emotions or chart the emotions of multiple characters. Track the types of emotions experienced by the character(s), the size of the emotions, and what emotional clues are used.

Does a character experience or express large or small emotions differently? How do the biggest emotions line up with the biggest plot moments?

Exercise 2: Emotion reversal

Write about a small emotion you had in a large way—with several paragraphs and a layering of emotional clues. For example, spend a significant amount of time writing about mild irritation at no ripe avocados, a small amount of joy from getting the day’s Wordle, etc.

Now, write about a large emotion you had in a small way. This might be a phrase or a few sentences. You might dismiss the large emotion, compare it to something else and move on, etc.

Now, reflect. While often it’s useful to write about bigger emotions in a big way, and smaller emotions in a small way, in what circumstances would it be useful to do the reverse?

Exercise 3: Planning (or revising) a story

Plan out a novel that you intend to write. Which three scenes do you want to have the biggest, most explored emotions? How will the placement of these emotional scenes help the story? (You can also do this with a short story—however, choose one scene or moment to have the biggest, most explored emotions.)

If you are revising a story, find which scenes already have the biggest, most expressed emotions. Are these the scenes that should have the most emotional weight? Are they expressing or layering in the most effective way? As necessary, revise.

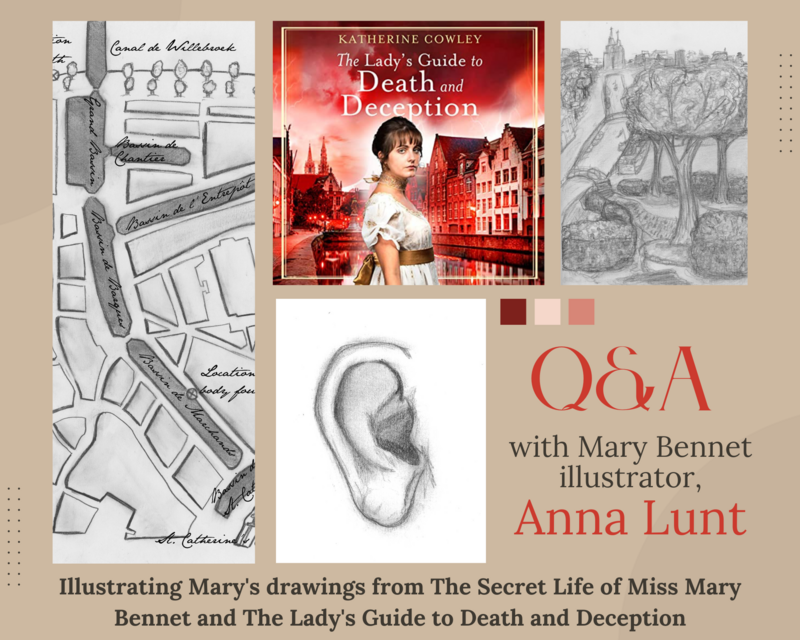

Q&A with Mary Bennet Illustrator, Anna Lunt

I am so thrilled today to be joined today by illustrator Anna Lunt, to talk about creating the interior illustrations for my Secret Life of Mary Bennet series.

In Pride and Prejudice, Lady Catherine de Bourgh judges Elizabeth Bennet for the fact that none of her sisters know how to draw. I decided, while writing my own series, that Mary would have always wanted drawing lessons. These lessons become a major part of the first book in the series, and then she continues to use her drawing skills in her work as a spy.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh, from the 2005 version of Pride and Prejudice

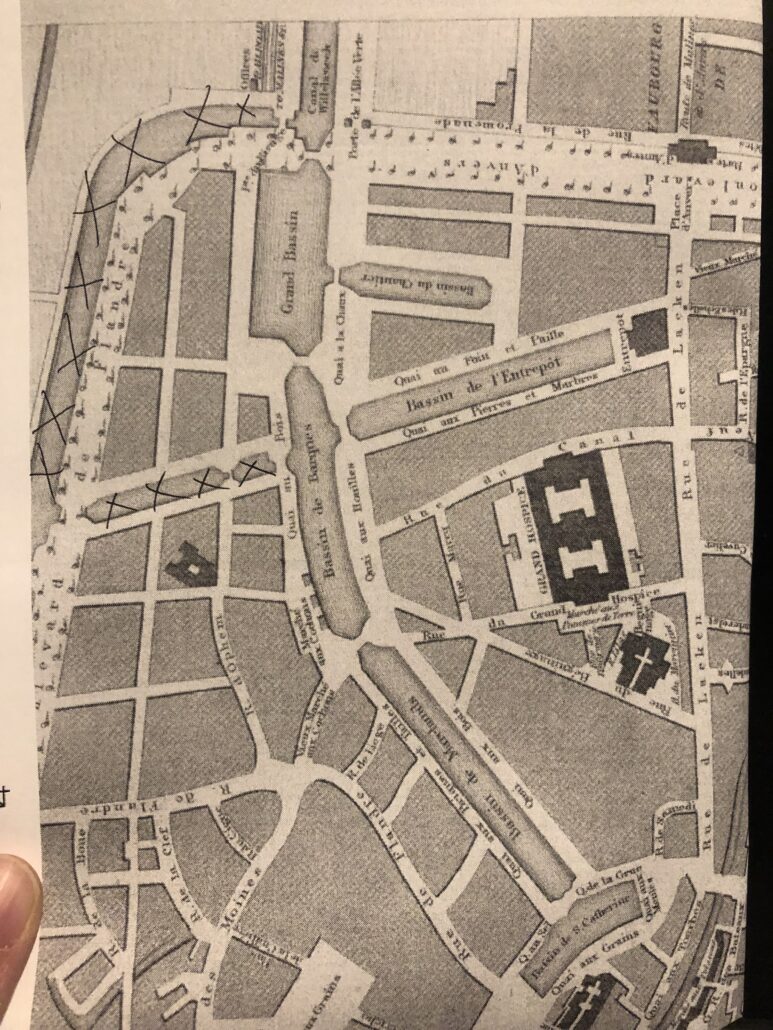

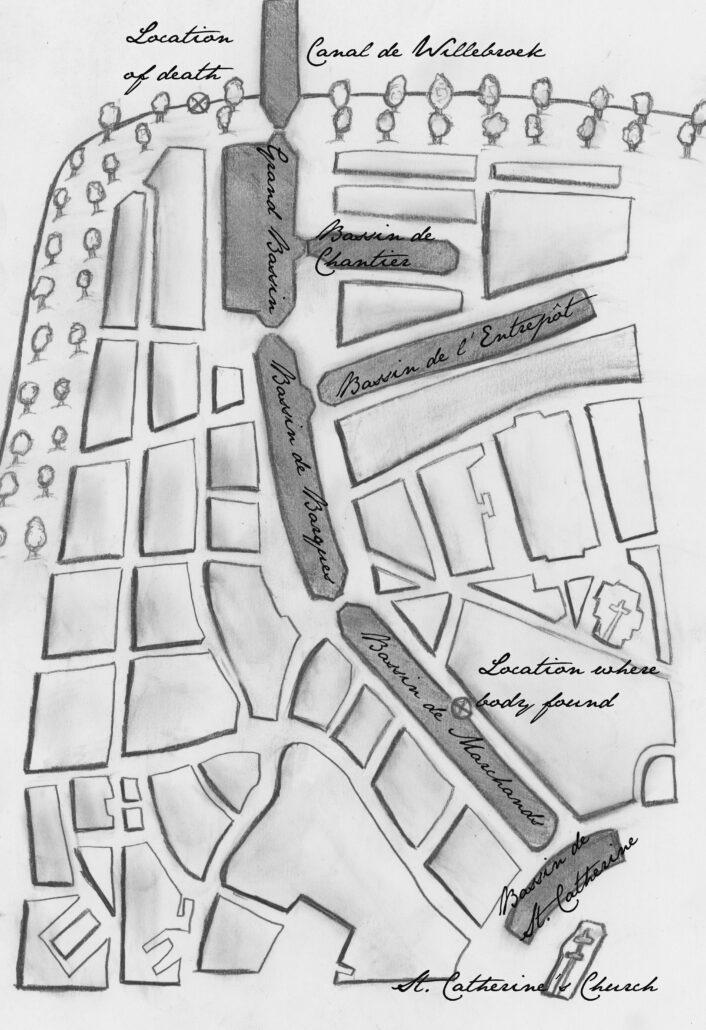

The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet contains one illustration, Lady Trafford’s ear, which Mary Bennet draws in a letter to her sister Jane. The third book in the series, The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception, contains two illustrations: Mary Bennet’s drawing of the crime scene, and a map of the basins in Brussels, with relevant spots marked (i.e. the location of the dead body).

The real artist behind these drawings is Anna Lunt, illustrator and writer extraordinaire. I hope you enjoy this interview with her, in which she talks about creating the illustrations for the Mary Bennet spies series, as well as her watercolors, her vineyard, and her other projects.

Q: How did you decide on what style to do the drawings? How did you approach representing the art of a fictional character?

Thank you for the chance to chat about the sketches in the Secret Life of Mary Bennet series! It was so fun to step into Mary’s shoes and attempt to draw for her hand. I first became familiar with Mary’s story from the early drafts we reviewed in our writing critique group long before Kathy was even submitting to agents. I love how in the first book how Mary finally gets a chance at developing skills–to take French lessons and drawing lessons–after being in a family where she was overlooked and forgotten.

When Kathy asked if I could do an ear drawing for Mary’s letter, she supplied a bit of the chapter so I understood the context. I’ve always found Mary very relatable and using the clues I had about her, I tried to step into a character who had some drawing instruction and imagine the details that she would notice. The fact that she was drawing the ear of Lady Trafford was a delightful insight into Mary’s character.

Q: Tell us a little more about your artistic process in creating these drawings. Did you do quick sketches first, plan it out, or use models? How many revisions did you make?

It was a bit different for each sketch.

For the ear, I did a search online for “short haircuts of older women” and studied ear after ear to find a model for Lady Trafford’s distinguished ear. When I found a model I liked I did a few sketches. One was rougher and the other with more attention to blending the shading. I sent both to Kathy and she chose the blended shading.

For the map, Kathy had a map for me to use as a reference, with a few details to adjust for the time period. I enjoyed outlining the landmarks and shading in, and even leaving smudges as that would be how a drawing for Mary would look, especially if she had been blending with her finger.

I attempted some penmanship on a draft of the map, but when I happened upon the Jane Austen font online, I was very excited to find a better representation of the period’s handwriting. I scanned my drawing and added the text on my computer.

A cropped portion of a map from 1837, which was given by the author to Anna Lunt as a model for the map. Note that some of the canals which did not exist in 1815 have been crossed out.

Mary Bennet’s map of the crime scene in Brussels, by Anna Lunt (included in The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception)

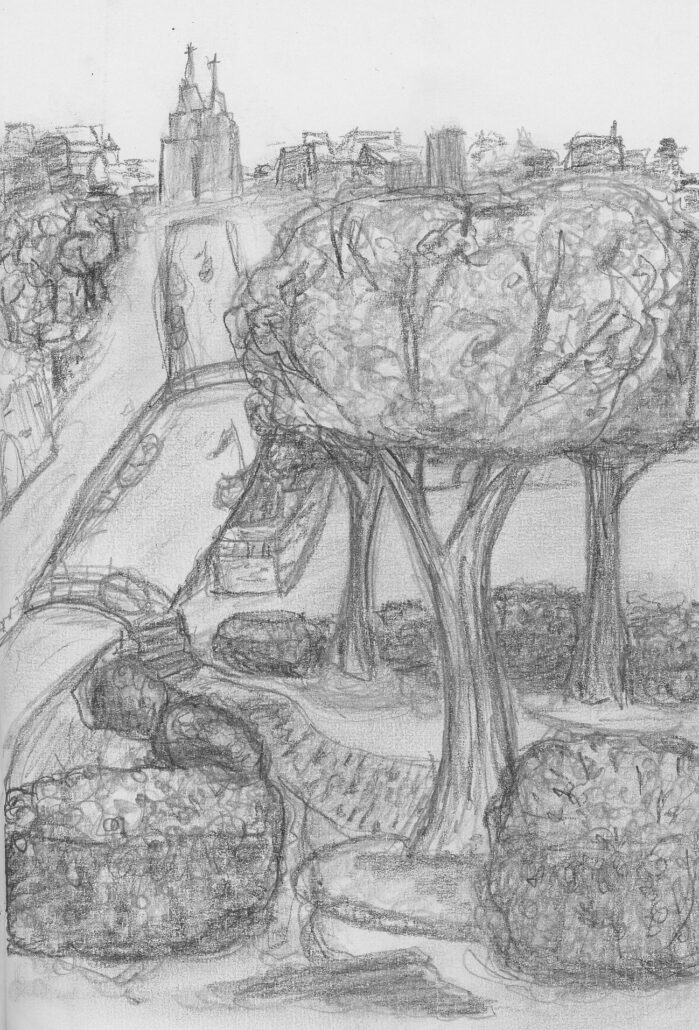

The crime scene sketch was the hardest one, as the only thing we had to help me imagine the view of the basins was from a painting, and the vantage point was wrong. I did rough sketches of the painting to learn details, but we needed the tree to be the focus of the sketch. I did many iterations to figure out what elements to include. I love that Kathy wanted to make sure I showed boats on the basins. That was my favorite part! As I sketched, I imagined standing there in the world I had mapped out in the other sketch. It felt right once I added the bushes and blood trail–Although, I kind of wish I’d put raindrop marks on it, as Mary did get caught in the rain as she finished her drawing.

Q: When you’re not channeling a Regency spy, what type of art do you normally create? Can you show us (and tell us about) a few sample pieces from your portfolio?

I love creating in watercolor and primarily create art geared toward a child audience–So quite different from historical mystery! I write as well and love creating picture book stories that incorporate animals, humor, growth, and compassion.

I love painting birds, so they often find their way into my pieces.

This one features one of my goats, Vincent van Goat. He is also the inspiration for many stories. You can tell he is quite pleased with himself sitting upon the eggs for his friend, but he also has no idea what is coming.

I love working in watercolor because for me it is very much about the process. I love mixing colors, I love whisking my brush across the page. I love the sound of swishing my brush in my water jar.

Q: Those who follow your Instagram feed know that you also have a farm. Tell us about your farm and how it influences your art.

Link to Anna’s Instagram feed

We’ve lived on this vineyard for five years and have gradually been transforming it into a homestead. We raise chickens, ducks, geese, rabbits, and goats… also have cats and a dog. My husband, Bryce, grew up on a ranch so this lifestyle was very natural to him, but so new to me! I enjoyed living here the first few years and found inspiration in it, but the animals and such were very much Bryce’s thing. Then last year at the very end of a tough harvest season, Bryce broke his foot and couldn’t even walk out in the yard. I took over responsibility for EVERYTHING, including two milk goats and bottle-feeding baby goats. I was completely immersed in the care of all the things and it transformed me. Not surprisingly, that is when a shift began to happen in my art as well. It’s hard to explain, but my creativity is very much intertwined with being outside and caring for my animals and gardens. It fuels my spirit and my creativity. My connection with God. One of my sisters came to visit our farm for the first time recently and she said, “I can see your inspiration now, it makes sense.” So visually my farm influences my art, but it’s also something much, much deeper. I truly love living here and love continuing to learn and find inspiration all around me.

Q: What is your background in art? How did you learn to draw and paint?

In junior high and high school, I loved creating and took a lot of art classes and even did private instruction with Andrea Kirk, but decided not to pursue art in college. I took creative writing classes at BYU and discovered a passion for picture books in Rick Walton’s class and knew in my heart someday I would write and illustrate my own stories. After graduation, while my husband was in grad school, I wrote and dreamed up stories as we welcomed our first child. After my second child was born, I found our local library had a watercolor instructor who did lessons, so I went every week! I was in heaven. I learned many techniques but mostly did portraits. I still hadn’t stepped into the world of narrative illustration. When I moved to Michigan and had my third child, I learned Kathy had a writing group. I jumped on the opportunity to meet monthly with writers and develop my imagination and confidence. After my fourth baby was born, I knew it was time to work beyond my perfectionism, and I took steps every day to draw and paint. It was the pandemic, and I felt like I was in survival mode caring for four young children, but even on hard days I read to my children and paid attention to the art that spoke to my heart. I have been working at it for 2 ½ years now. I’ve been blessed with many opportunities to learn, like working on the Mary illustrations and even a mentorship with the amazing author and illustrator Dow Phumiruk. And so my journey in art has been gradual, but it is also something that has been a tremendous joy for me to continue to grow and develop in.

Q: What advice would you give someone who wants to begin their journey as an artist?

Most of the reasons that kept me from pursuing art were my own limitations. Learning to shift my mindset and be open to possibilities made all the difference, but it’s taken years to get out of my own way and drop my excuses. I couldn’t do it alone. A supportive critique group, mentors, coaches, teachers, and family have helped me to keep moving forward. If you really want to learn, believe in yourself and go for it. Drawing is a skill you can learn, just like Mary! Find an instructor, connect with other creators, listen to creative podcasts, cultivate a connection with your spirit, or simply get outside and observe nature. Most importantly, do a little creating each day. Create the time, because it is time well invested. Believe that those little steps will add up to something.

Q: What are your goals for your art and your writing in the future?

I’m working toward publishing my own picture books! I have the story about Vincent van Goat that I’m currently illustrating and I’m also very excited about a religious picture book I’m working on about the gardens of God. Another project I’m working on is preparing art lessons: one geared toward children to go along with my Vincent van Goat book, and another for a more broad age range to teach watercolors as a way of connecting your mind, body, and spirit.

Thank you!

Thank you, Anna, for joining us to talk about creating the interior illustrations for the Secret Life of Mary Bennet series, as well as your own art and other thoughts on art and creation!

I highly recommend Anna Lunt’s monthly newsletter, which has thoughts on creativity and life, as well as insights into her drawing and other projects.

You can also follow Anna Lunt on Instagram, and see more of her portfolio on her website, Picture Book Homestead.

Mary Bennet E-Book Sale + 5 of my favorite Austenesque Books

Mary Bennet E-Book Sale

In celebration of the upcoming release of The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception, my publisher has placed the e-book of The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet on sale for $.99 (or your local equivalent) for the weekend!

If you’ve been waiting to read the book, need a digital copy to go with your print book/audiobook, or would like to share it with a friend, now is the perfect opportunity. Make sure to grab your copy by the end of September 4th, 2022, so you don’t miss this sale price.

The e-book can be found worldwide through Kindle (Amazon), Kobo, Nook, Apple Books, and possibly other platforms. A few of the links:

The Best Books Inspired by Jane Austen

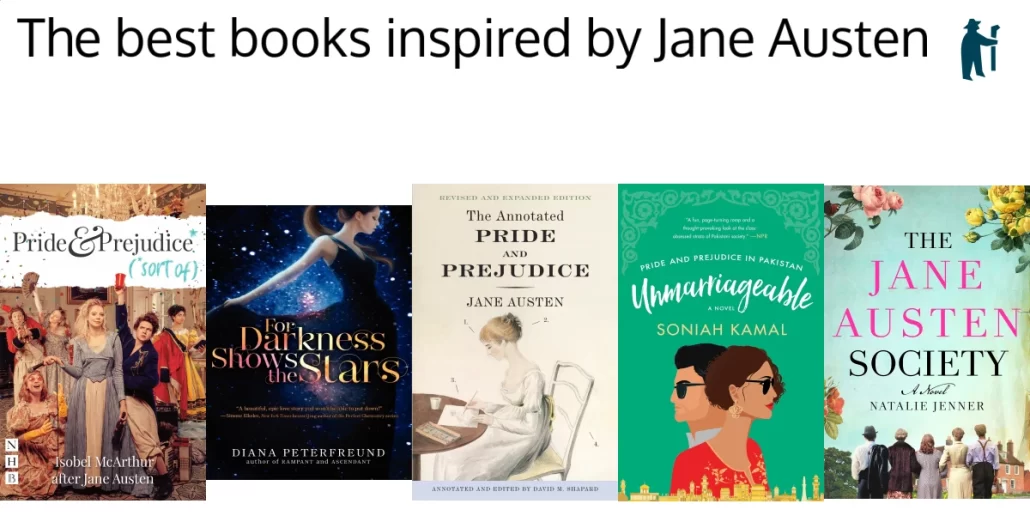

If you haven’t heard of Shepherd.com, it’s a really fun new book discovery website. A lot of book websites use algorithms to try to guess what you might like to read, but I like how Shepherd is about people sharing their personal recommendations.

I wrote a guest post for Shepherd on 5 of the best books inspired by Jane Austen. I have so many favorites, and it really is impossible to choose just five, so I tried to choose ones that take Jane Austen from very different angles.

Another list I found on Shepherd which just added multiple books to my to read pile is by author Roy Adkins and gives some of his favorite books about Jane Austen herself.

And that’s all for this post! Make sure to subscribe to my newsletter if you’d like exclusive details about The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception.