I Just Bought My First Barbie + My Thoughts on the Barbie Movie

This week, I–a thirty-something year old woman–bought my very first Barbie doll.

I never owned a single Barbie when I was a child. Yet I desperately wanted one. I loved going over to friends’ houses and playing with Barbie dolls, dream houses, and pink cars.

I never asked for a Barbie because I assumed that my parents would be opposed to them and everything Barbie stood for (a sexualized, unattainable, and perhaps undesirable version of reality–clearly they wouldn’t that want that).

Years later, one of my younger sisters had Barbies, and I realized that I should have asked. Maybe a Barbie would have been outside of my family’s budget, but maybe it would have become that coveted Christmas present.

Fast-forward to myself as an adult, and my daughters own dozens of Barbie dolls, several Chelsea dolls, and a few pets. And, lest I forget, a single Ken doll. I have bought Barbies for them and Barbies for birthday presents, as if I am trying to make up for lost time. And I’ve spent many hours playing Barbies with my children. One of my youngest’s favorite versions involves designating half of the Barbies as villains and often includes kidnapping, tying Barbies up with ropes, and all manner of treachery and shenanigans.

Then came the Barbie movie. Not those animated movies that my daughters used to watch that I find supremely annoying, but THE 2023 Barbie movie.

I knew, from the moment the first Barbie teaser trailer dropped, that I would love the Barbie film. After all, 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of my favorite films, and if a director can manage to do a perfect homage, remaking every shot but with baby dolls, then I’m on board for the ride. (I’ll spare you the 1000-word analysis of the opening sequence of 2001…but know that this analysis is ever in my heart.)

Earlier this week, I was feeling very prepared for the Barbie movie:

- Group of friends to go with? Check.

- Tickets to opening night? Check.

- Outfit? Check. (Matching Barbie shirts with customized “This Barbie is…” statements on the back.)

But I wanted a Margot Robbie Barbie doll. My internal voices, the same voices that led me to not ask for a Barbie, told me:

- I don’t need a Barbie doll

- I’m an adult–clearly I don’t need a Barbie doll

- This is a waste of money

- I’m going overboard for this movie, when I’m not even a Barbie superfan

I decided not to listen to the voices. I bought the Barbie doll.

And then I brought my very own Barbie–my very first Barbie–with me to the movie.

The showing was absolutely packed, mostly with women, but also with men and children. And the film was a delight. It was a perfect mix of comedy, cultural references, and simultaneous lighthearted embracing and mocking of fandom and society, mixed with touching, heartfelt moments.

One of the things I’ve struggled with throughout my adult life is a feeling of internal conflict. Of wanting to be many things, but feeling like my wants and desires don’t match up with all the many versions of what the different cultural, social, religious, and family groups I am a part of think I should be. It’s something I’ve tried to work through with therapists, but almost always I feel this internal tension, this sense that I’m not enough, this almost-wish that I could just happily fit into one of the roles that has been prescribed for me, and somehow just feel happy and content in this role. Could I just not want more? Could I just not want something different? Wouldn’t life be better that way?

This movie–Barbie’s journey, Ken’s journey, Gloria’s journey, Sasha’s journey–made me feel less alone. It made me feel like maybe I’m not the only one struggling with this. In fact, this is something everyone faces–especially women. Like Barbie, I can be who I want to be. Like Barbie, I can take on many roles. Like Barbie, there will be challenges and conflict, and the path won’t always be clear. But I can keep trying.

I have no regrets about buying myself a Barbie doll.

West Michigan Event: Gilbert and Ivy (Vicksburg)

If you’re in Western Michigan and looking for some great author events this summer, Vicksburg, MI has a charming new bookstore, Gilbert and Ivy, and they have a summer speaker series.

I’ll be there on June 28th from 5:30-7:00 p.m., talking about my Mary Bennet series, answering everyone’s questions, and leading a free letterlocking activity (Lady Trafford taught Mary how to properly lock her letters; now I’ll teach you).

If you’re interested in attending, you’re encouraged to RSVP on Eventbrite (Gilbert and Ivy).

#67: Creating an Emotional Map: Making Interconnected Emotions

We’ve talked a lot about writing emotions over the past months, with posts on:

- Planting clues to what characters feel

- Conveying emotion through character thoughts and free indirect speech

- Additional internal emotion techniques

- The size or degree of character emotions

- Different ways that characters deal with and express emotions

- Evoking emotions through external objects (objective correlative)

I wanted to do one final post on emotions, that ties everything together, so today I’ll be talking about creating an emotional map, or making a characters emotions in a single scene connected to their emotions in other scenes.

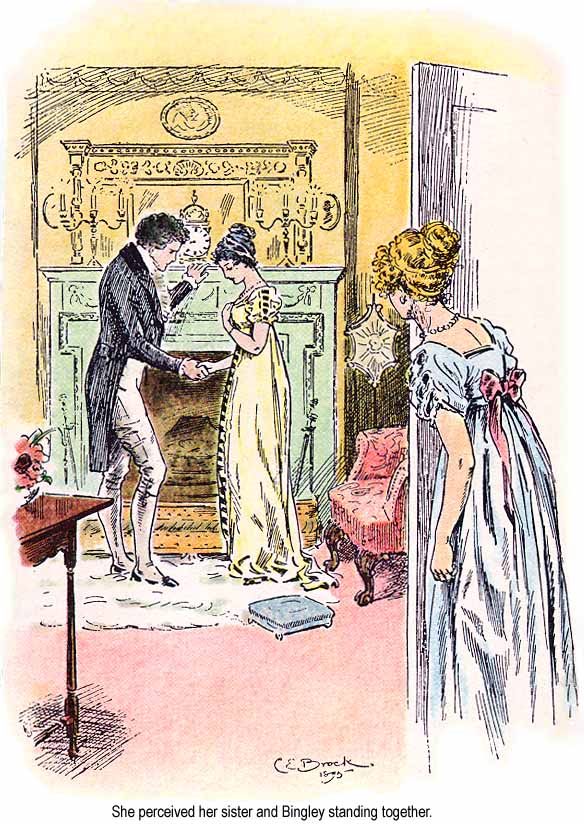

Near the end of Pride and Prejudice, Jane, the eldest of the Bennet sisters, becomes engaged to Mr. Bingley. Elizabeth opens a door and sees Jane and Mr. Bingley standing next to the fireplace, rather close to each other. Jane and Bingley quickly move apart, looking embarrassed.

Not a syllable was uttered by either; and Elizabeth was on the point of going away again, when Bingley, who as well as the other had sat down, suddenly rose, and, whispering a few words to her sister, ran out of the room.

Jane could have no reserves from Elizabeth, where confidence would give pleasure; and, instantly embracing her, acknowledged, with the liveliest emotion, that she was the happiest creature in the world.

“’Tis too much!” she added, “by far too much. I do not deserve it. Oh, why is not everybody as happy?”

Elizabeth’s congratulations were given with a sincerity, a warmth, a delight, which words could but poorly express. Every sentence of kindness was a fresh source of happiness to Jane. But she would not allow herself to stay with her sister, or say half that remained to be said, for the present.

“I must go instantly to my mother,” she cried. “I would not on any account trifle with her affectionate solicitude, or allow her to hear it from anyone but myself. He is gone to my father already. Oh, Lizzy, to know that what I have to relate will give such pleasure to all my dear family! how shall I bear so much happiness?”

Jane’s emotions are expressed primarily through her physical actions and through her dialogue (including the diction, word choice, and use of emphasis). It’s an effective scene at conveying emotions, but what makes it work is largely based on what Austen has established in the rest of the book.

An 1895 illustration by CE Brock of Jane and Bingley together, immediately after becoming engaged. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

This post-proposal scene is in conversation with dozens of other scenes which have demonstrated Jane’s emotions. We’ve seen how reserved Jane is in outwardly expressing emotions, especially in groups of people (of Bingley she offers only “cautious praise” to everyone but Elizabeth). We’ve seen the pleasure Jane takes from little interactions with Mr. Bingley and his sister. We’ve seen her hope for an engagement. And then we’ve seen her despair—her utter, all-encompassing despair—when Mr. Bingley leaves without a word to her (though his sister Caroline almost gleefully writes to Jane of the news).

At various points Elizabeth and other characters analyze Jane’s emotions, sensing Jane’s devastation beneath all her attempts to insist that “He will be forgot, and we shall all be as we were before.”

At one point, Elizabeth reexamines all the letters that Jane has written to her:

They contained no actual complaint, nor was there any revival of past occurrences, or any communication of present suffering. But in all, and in almost every line of each, there was a want of that cheerfulness which had been used to characterize her style, and which, proceeding from the serenity of a mind at ease with itself, and kindly disposed towards everyone, had been scarcely ever clouded. Elizabeth noticed every sentence conveying the idea of uneasiness…

Jane’s utter joy at her engagement if effective because of all of these other scenes. Her happiness is the culmination of her earlier attachment to Mr. Bingley, and provides stark contrast to her despair.

An individual emotion does not occur in a vacuum. The emotion found in a single scene is simply a leaf or a branch on a character’s emotional tree. It’s a single block in a Lego tower, part of a larger structure which is more magnificent and complex than an individual Lego can be on its own.

When I am revising a story, I like to consider a character’s individual emotions as part of a larger emotional map. After all, a character has emotional valleys and mountains, fast-moving rivers and muddy bogs. There are cities and villages: parts of the map where a series of emotions relate to a particular person, object, incident, or theme. Some characters experience their emotional map as a journey: they have an emotional arc as their emotions, or ways of dealing with their emotions, change. Other characters circle through the map in a regular fashion, or spend most of their time in a single area of the map. For some characters, we receive only a glimpse of their emotional map, while for others, we explore broad swaths of it with them.

Whenever I am stuck trying to figure out a character’s emotion, or I feel like I’m not effectively conveying that emotion on the page, I think about the characters emotional map and how this emotion connects to all the others in the story. Doing so always helps me to understand the character’s emotion in the moment and what will best convey that to the reader.

1. Write a page about how your current emotions connect to prior emotions you have had. You can focus on a specific emotion or on a specific incident. Reflect on what your own emotions can teach you about the emotions of your characters.

2. Use a visual form to analyze one of your character’s emotions and how they connect to each other. This might be a map (or even a treasure map), a tree, a building/structure, or anything else you think would be an effective medium. You could create this with paper or other objects, or you could print out a map/floorplan/picture, etc. and add things to it. Personally, I like doing this in a tactile way, with pen, paper, glue, etc., but you can do it virtually as well.

3. Find one of your favorite expressions of emotion in fiction, and then find two or three other passages/scenes in the same work that have a strong connection to this emotion (whether in building to it, contrasting with it, foreshadowing it, etc.).

#66: Evoking Emotions Through Objective Correlative (External Objects)

A powerful way to evoke emotions—to make them feel real, material, and defined—is through the use of objective correlative, or using external objects that the reader connects with an emotion. And of course, Jane Austen is a master at this.

In Austen’s novel Emma, the character of Harriet has difficulties with love (largely because of Emma’s interference). She becomes head-over-heels for Mr. Elton, and is devastated when she learns that he is not interested in her. Mr. Elton leaves town for a time period, and comes back with a bride, Augusta Hawkins. A few months later, a ball is held, and even though it is tradition for married men to dance with the unmarried ladies, Harriet is snubbed by Mr. Elton.

After the ball, Harriet comes to visit Emma, bringing with her a parcel on which she has written “Most precious treasures.” She wants to destroy these treasures, and she wants Emma as a witness.

Inside are two objects. First, is court plaister which Mr. Elton had once played with. Dictionary.com defines court plaister as “cotton or other fabric coated on one side with an adhesive preparation, as of isinglass and glycerin, used on the skin for medical and cosmetic purposes.” In essence, Harriet has kept an expensive Band-Aid.

The other object is a “superior treasure,” for Harriet finds it even “more valuable, because this is what did really once belong to him.”

She reveals the object to Emma:

It was the end of an old pencil,—the part without any lead.

Harriet has kept Mr. Elton’s pencil for months after his marriage to someone else. The tiny end of an old pencil stub, without any lead—it’s an evocative image, conjuring up a series of emotions for the reader. We feel pity for Harriet, we feel sympathy for her love and her heartbreak as we understand the depth of her feelings, and we feel negatively towards Emma. After all, it is Emma’s interference which has caused all this, has caused a discarded pencil stub to be another woman’s most prized possession.

This is a classic use of objective correlative.

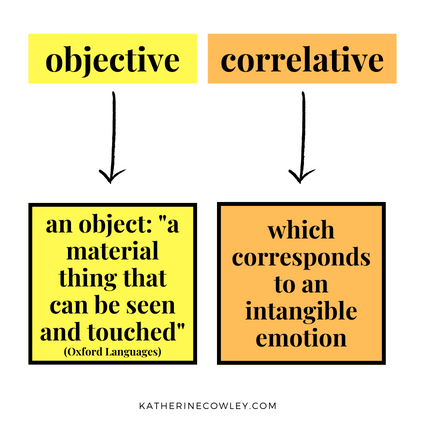

Defining Objective Correlative and Its Powerful Emotional Impacts

According to scholar George P. Winston, the term objective correlative was coined by the American painter Washington Allston in 1843.

Allston’s definition of objective correlative is rather opaque. In his book Lectures on Art, he talks about how cabbages are different than cauliflowers—a cabbage can’t just change into a cauliflower, for it is a cabbage, and has its own physical properties and meaning.

Picture of a woman experiencing emotions while accompanied by cabbage and cauliflower (and broccoli). Washington Allston would approve. Photo by Ivan Samkov from Pexels.

Then Allston writes:

So, too, is the external world to the mind; which needs, also, as the condition of its manifestation, its objective correlative. Hence the presence of some outward object, predetermined to correspond to the preëxisting idea in its living power, is essential to the evolution of its proper end,–the pleasurable emotion.

In other words, the things that happen inside our heads—and I would like to add, inside our hearts—are difficult to understand or to manifest. It’s so easy to go about our days and not understand why people are making the choices they’re making. It’s so easy to feel like others don’t truly understand our emotions—or that we don’t truly understand the emotions of those around us.

This becomes tricky for the writer. How do we take an emotion, something which is inherently abstract, intangible, and in many senses, undefinable, and make it feel real and substantial to the reader? There are numerous techniques that writers, including Jane Austen, use, including body language, facial expressions, dialogue, silence, free indirect speech, punctuation, syntax, repetition, and physical sensation, to name a few.

Allston doesn’t address these approaches, in part because he is a painter, interested in things which can take visual, material form on the canvas. But his advice can be useful for writers as well: he says that what we need do is manifest the mind—manifest the internal, unfathomable emotion—by finding a concrete, external object that can correlate to what is happening on the inside.

For Washington Allston, objects are “predetermined to correspond” to a “preexisting idea” or emotion, and I agree that there are some objects that have a standard emotion that are attached to them. For instance, in Western culture a coffin often evokes emotions related to sadness and mourning.

Yet we don’t automatically associate a pencil stub with the powerful emotions that Jane Austen conveys through it. So in order see the true power of objective correlative, we need a more expansive definition.

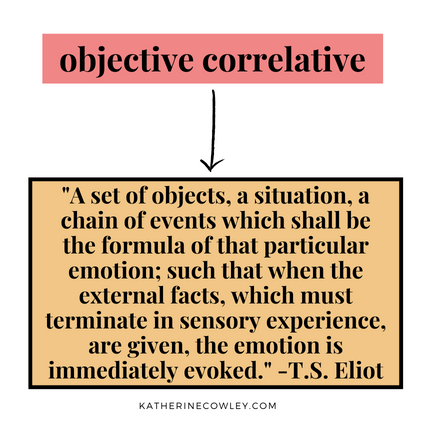

While others used Allston’s term, it was T.S. Eliot who popularized it in his 1919 essay, “Hamlet and His Problems.” He writes:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an “objective correlative”; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.

For T.S. Eliot, the emotional meaning of the object is contextual—it’s dependent on what happens around it in the poem or story. Objects are part of a situation and a chain of events, and it these groupings which create a formula for a particular emotion.

Let’s consider a few more examples of objective correlative in Austen’s work to see how we can apply this to our own writing.

In Sense and Sensibility, Marianne sees and reflects on the dead leaves with all the passion of romanticism. The leaves embody Marianne’s endless emotions and grief as she loses her home. The podcast The Thing About Austen has an excellent episode on Marianne’s dead leaves.

In Mansfield Park, the play Lovers’ Vows becomes an object which conveys emotions, both of Fanny and the other characters. This is truly a set of objects: there’s the script itself, the assignment of roles, all the preparations, and of course the physical set which is built and then torn down by Fanny’s uncle, leaving the play unperformed.

In the uncompleted novel Sanditon, the characters drive past Mr. and Mrs. Parker’s old house on the outskirts of Sanditon, which they have left in order to live in a new house, in the heart of the action, so they can pursue Mr. Parker’s dreams for Sanditon. Both Mr. and Mrs. Parker see different things in the old house and its gardens—they notice different attributes, and the things they notice and comment upon reveal that they feel very differently about the past, present, and future. While Mr. Parker praises it as “the house of my forefathers,” he remarks that it is “built in a hole” and that he is happy to have moved on. Mrs. Parker, on the other hand, says that it was a “very comfortable house,” and notices the beautiful garden, the places for the children to run and play, the desirable shade, and how it is always sheltered from the effects of winds and storms. It is clear that she misses the house and wishes they could return to it, and it is clear that turning Sanditon into a resort town is her husband’s dream, not hers.

It is important to note that Jane Austen uses objective correlative with moderation. None of her novels are packed with objective correlative, and not every object included in the novels is meant to create an emotion. Yet when she does use it, she does so to great effect.

How to Use Objective Correlative to Convey Emotions in Fiction

There are a number of principles we can take from how Jane Austen uses objective correlative:

- Objects can be used to correspond to emotions large and small.

- Some objects are important or evocative in their own right, but many are made important by the attention given to them. The context and history of the object can also help imbue meaning.

- In crafting fiction, it’s important to consider what people do with the objects or how they interact or talk about them.

- Highlighting the characteristics or attributes of an object can help open up our understanding of the corresponding emotion.

- The same object can engender different emotions for different characters. While sometimes an object reveals only the emotions of the main character, it can also reveal the emotions of other characters in the story.

- An object can be used in a single scene (like the pencil in Emma), or in sequence of scenes (like the play in Mansfield Park).

- In addition to revealing the emotions of characters, objects can create emotions in the reader.

I want to use one more example from Austen, to further explore the last two points: how an object can be used in a sequence of scenes, and how an object can create emotions in the reader.

Using Objective Correlative to Build to Moments of Emotional Weight for the Reader

In his definition, T.S. Eliot talked about a SET of objects and a CHAIN of events which immediately evoke a particular emotion in the audience.

One of the most effective ways to create a strong emotion in a reader is to build emotion with an object over time.

A great example of this is in Sense and Sensibility. (Warning: there will be major spoilers for the novel below!) As discussed in a previous post, Elinor keeps her emotions mostly inside. So how do we know that she is feeling strongly, and how do we as readers feel strongly with her? And how can we as readers draw parallels between Elinor’s heartbreak and her sister’s heartbreak, even though they are both such different characters? Austen achieves all of this through objective correlative.

The objects used by Austen are locks of hair.

Locks of hair inlaid in a pearl bracelet. This piece was made in England between 1790 and 1810, and is owned by the Walters Art Museum. Image used through Creative Commons license.

Austen sets up these objects early on in the novel as meaningful tokens of affection when young Margaret tells Elinor that she saw Willoughby take a lock of Marianne’s hair:

Last night after tea, when you and mama went out of the room, they were whispering and talking together as fast as could be, and he seemed to be begging something of her, and presently he took up her scissors and cut off a long lock of her hair, for it was all tumbled down her back; and he kissed it, and folded it up in a piece of white paper; and put it into his pocket-book.

In a later chapter, the man Elinor loves, Edward, comes to visit. He is wearing a ring which contains a lock of hair. Marianne immediately assumes it belongs to Elinor, and teases Edward by pretending to wonder if the hair belongs to Edward’s sister, Fanny:

[Marianne] was sitting by Edward, and in taking his tea from Mrs. Dashwood, his hand passed so directly before her, as to make a ring, with a plait of hair in the centre, very conspicuous on one of his fingers.

“I never saw you wear a ring before, Edward,” she cried. “Is that Fanny’s hair? I remember her promising to give you some. But I should have thought her hair had been darker.”

Marianne spoke inconsiderately what she really felt—but when she saw how much she had pained Edward, her own vexation at her want of thought could not be surpassed by his. He coloured very deeply, and giving a momentary glance at Elinor, replied, “Yes; it is my sister’s hair. The setting always casts a different shade on it, you know.”

Elinor had met his eye, and looked conscious likewise. That the hair was her own, she instantaneously felt as well satisfied as Marianne; the only difference in their conclusions was, that what Marianne considered as a free gift from her sister, Elinor was conscious must have been procured by some theft or contrivance unknown to herself. She was not in a humour, however, to regard it as an affront, and affecting to take no notice of what passed, by instantly talking of something else, she internally resolved henceforward to catch every opportunity of eyeing the hair and of satisfying herself, beyond all doubt, that it was exactly the shade of her own.

Edward’s embarrassment lasted some time, and it ended in an absence of mind still more settled. He was particularly grave the whole morning. Marianne severely censured herself for what she had said; but her own forgiveness might have been more speedy, had she known how little offence it had given her sister.

Elinor is secretly pleased that Edward wears her hair in a ring. This is a promise of hope, a promise of affection, a promise that someday they might wed. And all of this emotion is embodied in a lock of hair.

A memorial ring from 1804 or 1805 with locks of hair set between pearls. Mourning rings were given out to family and close friends at funerals, and often included locks of hair. In Sense and Sensibility it is clear that a ring with a lock of hair was not assumed to be a mourning ring, and that it was quite common for the ring to commemorate a living person. This ring is also owned by the Walters Art Museum. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

A few chapters later, as the chain of events progresses, Austen once again uses this same lock of hair. This is the prime example of what T.S. Eliot’s emotional formula, for she has set up the object to produce a very specific emotion from the reader.

What happens is that Elinor meets Lucy Steele. Lucy deduces that Elinor is in love with Edward, but Lucy is also in love with Edward, and she wants to mark her territory.

Lucy makes Elinor promise not to tell anyone what she is about to share, and then she confides in Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward for four years.

Elinor cannot believe her, but Lucy provides more and more evidence, including dates and places that align with Elinor’s knowledge of Edward’s whereabouts, a miniature painting of Edward, and a letter written in Edward’s hand.

Then Lucy manages to completely decimate both Elinor and the reader’s emotions by bringing back a reference to the key object:

“Writing to each other,” said Lucy, returning the letter into her pocket, “is the only comfort we have in such long separations. Yes, I have one other comfort in his picture, but poor Edward has not even that. If he had but my picture, he says he should be easy. I gave him a lock of my hair set in a ring when he was at Longstaple last, and that was some comfort to him, he said, but not equal to a picture. Perhaps you might notice the ring when you saw him?”

“I did,” said Elinor, with a composure of voice, under which was concealed an emotion and distress beyond any thing she had ever felt before. She was mortified, shocked, confounded.

We too are mortified, shocked, and confounded, and we feel it deeply because these emotions are attached to a physical object. We thought the ring and the hair meant one thing, and to discover without a doubt that it means something else—this immediately evokes a reaction.

For me, this is the most powerful use of objective correlative in Sense and Sensibility, yet Austen continues to use locks of hair for emotional effect by bringing back the other lock of hair: Marianne’s.

When Marianne and Elinor spend the season in London, Marianne is snubbed by her love, Willoughby, and Elinor finds Marianne on her bed, completely and “violently” distraught. Next to Marianne, she discovers a letter from Willoughby, who has returned Marianne’s lock of hair.

It is with great regret that I obey your commands in returning the letters with which I have been honoured from you, and the lock of hair, which you so obligingly bestowed on me.

Marianne had asked for her letters and the lock of hair back, “if your sentiments are no longer what they were.” But she did not actually want him to return the hair. As she tells Elinor, she thought they were engaged:

“I felt myself,” she added, “to be as solemnly engaged to him, as if the strictest legal covenant had bound us to each other.”

“I can believe it,” said Elinor; “but unfortunately he did not feel the same.”

“He did feel the same, Elinor—for weeks and weeks he felt it. I know he did. Whatever may have changed him now, (and nothing but the blackest art employed against me can have done it), I was once as dear to him as my own soul could wish. This lock of hair, which now he can so readily give up, was begged of me with the most earnest supplication. Had you seen his look, his manner, had you heard his voice at that moment!”

Marianne rereads Willoughby’s letter, and the reference to the lock of hair only makes her more upset:

“It is too much! Oh, Willoughby, Willoughby, could this be yours! Cruel, cruel—nothing can acquit you….‘The lock of hair, (repeating it from the letter,) which you so obligingly bestowed on me’—That is unpardonable. Willoughby, where was your heart when you wrote those words? Oh, barbarously insolent!—Elinor, can he be justified?”

Once again, Austen employs objective correlative to show the depth of Marianne’s emotion by attaching it to a physical object. And, like Elinor, we feel deeply for Marianne.

Having built up this chain of events, with this set of objects (the locks of hair), Jane Austen continues to use them to great effect, bringing up each lock of hair one additional time.

When Marianne is severely ill and almost dies, Willoughby comes to visit, and tries to justify and redeem himself to Elinor. He blames his fiancé for forcing him to break Marianne’s heart and return Marianne’s lock of hair.

“[Marianne’s] three notes,—unluckily they were all in my pocketbook, or I should have denied their existence, and hoarded them for ever,—I was forced to put them up, and could not even kiss them. And the lock of hair—that too I had always carried about me in the same pocket-book, which was now searched by Madam with the most ingratiating virulence,—the dear lock,—all, every memento was torn from me.”

Elinor is tempted to absolve Willoughby—his speech is long and passionate, and the way he talks about Marianne’s lock of hair is definitely a point in his favor. Yet he returned it and broke his heart (and behaved like a rascal in other ways).

A brooch containing hair, so you can wear someone’s hair in your own hair. This was made in the 19th century, and is part of the permanent collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, Lucy’s lock of hair is once again brought back. After marrying Edward’s brother, she writes one last letter to Edward, saying that she feels no ill will to him, and that she decided that she could bestow her affections elsewhere since she thought she had lost his. The postscript of the letter reads:

“I have burnt all your letters, and will return your picture the first opportunity. Please to destroy my scrawls—but the ring with my hair you are very welcome to keep.”

Oh, dear Lucy. You are married to Edward’s brother, but you want him to keep your lock of hair. You want him to treasure and remember you still.

In this case, Austen is creating a very different emotion. We are meant to laugh at Lucy—and this becomes a laugh of relief, and we do feel relief, for Edward and Elinor have finally been able to come together. Edward and Elinor are able to read the letter and move past it. As Shakespeare would say, “All’s well that ends well.”

Jane Austen does not reveal what Edward actually does with the ring and the lock of hair, but based on his words to Elinor, and what that lock of hair meant to Lucy, we can safely assume that he does not keep it.

It amazes me what a simple lock of hair can do in the hands of an author like Jane Austen. This is my favorite example of objective correlative in literature.

There will be one more Jane Austen writing lesson to wrap up the series on emotion—I will be talking about other ways to build emotion across multiple scenes. And as always, there are three writing exercises below.

Exercise 1: Think of a scene you have written that has an important emotion (the emotion can be important, whether it is a large or a small one). Now imagine that you’re a painter. Instead of painting the character with their facial expression, you’ve decided to paint an object that corresponds to their emotion. If you have artistic inclinations (or want to try something new), paint or draw a picture of the object. If not, search for images online to find a representation of the object that best captures your character’s emotions.

Exercise 2: Reread one of your favorite stories or rewatch one of your favorite shows. Find an example of objective correlative. Is the object used once or as part of a sequence? What is the character’s relationship with the object? What emotions does the object reveal, and what emotions does the object create in the audience?

Exercise 3: For a story idea that is either new or in early stages of development/writing, choose an object or set of objects that could be used in a sequence of scenes to create emotions for the reader. Try to use the object at least three times. What does the object mean to the characters? What do you want the object to mean for the readers?

Mary Bennet and Mr. Collins

In Jane Austen’s novel, Pride and Prejudice, several of the characters make good matches, not just financially, but emotionally and romantically. Elizabeth marries Mr. Darcy, and Jane marries Mr. Bingley. Other matches are more complicated, like Lydia’s marriage to Mr. Wickham, and Charlotte Lucas’ marriage to Mr. Collins. In fact, many readers have wondered if Mary Bennet and Mr. Collins might not have been more suited for each other. Why didn’t Mr. Collins marry Mary Bennet? And if they had married, would it have been a good match?

It’s Jane Austen’s fault that these questions are asked, for she planted seeds for these speculations in the text. At the same time, she clearly demonstrates what led Mr. Collins to choose Charlotte Lucas as his bride rather than turning to Mary Bennet. Let’s look at the sequence of events, as conveyed in the book:

- Mr. Collins proposes to Elizabeth.

- Elizabeth turns down Mr. Collins.

- Mrs. Bennet congratulates Mr. Collins on his engagement to her daughter. He explains that she turned him down, but that he also believes that despite her refusal, Elizabeth actually intends to marry him.

- Mrs. Bennet attempts to convince her husband to force Elizabeth to marry Mr. Collins. When Mr. Bennet refuses to do so, she tries—and fails—to convince Elizabeth on her own.

- Charlotte Lucas comes to visit the Bennets and finds the house in an uproar. Mr. Collins shows Charlotte civility, and she politely pretends not to notice the hubbub about the failed marriage proposal.

- Mr. Collins spends the rest of the day trying to ignore Elizabeth, and spends much of the time talking to Charlotte Lucas: “the assiduous attentions which he had been so sensible of himself were transferred for the rest of the day to Miss Lucas, whose civility in listening to him was a seasonable relief to them all, and especially to her friend.”

- The next day, the Bennets eat dinner with the Lucases, and Charlotte is so kind as to entertain Mr. Collins. (Austen lets us know that Charlotte’s actual “object was nothing less than to secure [Elizabeth] from any return of Mr. Collins’s addresses, by engaging them towards herself.”)

- The next morning—his very last day visiting Meryton—Mr. Collins walks towards Lucas Lodge. Upon seeing him from the window, Charlotte contrives to “accidentally” run into him in the lane. Mr. Collins proposes to Charlotte, and Charlotte accepts.

An 1894 illustration by George Allen of Mr. Collins proposing to Charlotte Lucas with “so much love and eloquence.” (Image in public domain; accessed through Wikimedia Commons)

- That evening, after becoming engaged to Charlotte Lucas, Mr. Collins must say farewell to the Bennets. He does not inform them of his engagement, but he does offer them his gratitude, affections, and wishes of health and happiness, even making a point not to exclude Elizabeth. Then he informs them that he plans to return soon to Longbourn, and the narrator finally tells us how Mary Bennet feels about the whole affair:

With proper civilities, the ladies then withdrew; all of them equally surprised to find that he meditated a quick return. Mrs. Bennet wished to understand by it that he thought of paying his addresses to one of her younger girls, and Mary might have been prevailed on to accept him. She rated his abilities much higher than any of the others: there was a solidity in his reflections which often struck her; and though by no means so clever as herself, she thought that, if encouraged to read and improve himself by such an example as hers, he might become a very agreeable companion. But on the following morning every hope of this kind was done away. Miss Lucas called soon after breakfast, and in a private conference with Elizabeth related the event of the day before.

Poor Mary Bennet.

Unlike her sisters, she actually values Mr. Collins’ abilities—or at least, “rated [them] much higher” than her sisters did. She is often—key word, often—struck by the “solidity in his reflections.” She does not think he is as intelligent or clever as she is, but she sees in him potential. He could read and improve himself. Even if he is not truly agreeable now, “he might become a very agreeable companion.”

Alas, Mary admits her feelings to herself to late to act on them. And even if she had admitted her feelings for Mr. Collins earlier, she would be unlikely to actively and swiftly pursue him, as Charlotte Lucas does. It is Charlotte’s willingness to converse with Mr. Collins, and then her direct pursuit of him, that leads to their marriage.

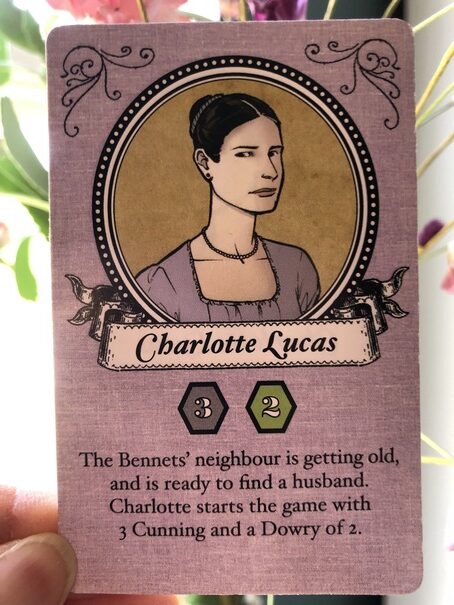

In one of my favorite card games, Marrying Mr. Darcy, Charlotte Lucas starts the game with a score of three cunning, which is rather fitting. (In the game, none of other characters start with any cunning, though they can acquire it throughout the game.)

In Melissa Leilani Larsen’s fabulous stage version of Pride and Prejudice, Mary actually makes Mr. Collins a pudding, which she is about to give him when she is cast out of the room by her mother so that he can propose to Elizabeth. I saw a Zoom production of the play in early 2021, and the way Mary said “But he hasn’t tried my pudding” almost brought me to tears. In this adaptation, Mary’s realization of her feelings for Mr. Collins comes earlier, but still too late.

Now let’s dive into the text of Pride and Prejudice to consider seven arguments for why Mr. Collins should have married Mary Bennet, and seven arguments on why that would have been a bad idea.

Arguments for a happy union between Mr. Collins and Mary Bennet, aka, why he should have married her

- Mary is interested in Mr. Collins, sees his positive qualities, and believes he could become an agreeable companion—and is not interest a base upon which something more substantial can be built?

- Mr. Collins doesn’t really care which sister he marries. He transfers his interest easily from Jane to Elizabeth upon a gentle nudge from Mrs. Bennet. Mary is also a Bennet sister! Could he not shift his interest to her?

“Mr. Collins meant to choose one of the daughters.” A humorous 1894 illustration of the five sisters, one of whom Mrs. Bennet has marked as unavailable, by Hugh Thomson. (Source: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons license.)

- They have similar speaking habits: Mr. Collins like to wax eloquently about any subject, and Mary likes to make profound statements on life. Neither individual is as clever, intelligent, or witty as they think themselves.

During a dinner conversation, Mr. Collins mentions that he frequently compliments Lady Catherine de Bourgh and her daughter.

Mr. Bennet says:

“It is happy for you that you possess the talent of flattering with delicacy. May I ask whether these pleasing attentions proceed from the impulse of the moment, or are the result of previous study?”

Mr. Collins replies with one of the best lines from the novel:

“They arise chiefly from what is passing at the time; and though I sometimes amuse myself with suggesting and arranging such little elegant compliments as may be adapted to ordinary occasions, I always wish to give them as unstudied an air as possible.”

Both Mr. Bennet and Elizabeth find his reply pleasingly absurd.

Earlier in the novel, after the Meryton assembly, Elizabeth is complaining of Mr. Darcy’s behavior to her sisters and Charlotte Lucas. Elizabeth says,

“I could easily forgive his pride, if he had not mortified mine.”

Mary immediately gives a long speech on pride, which, while it contains some insights, does not truly add to the conversation:

“Pride,” observed Mary, who piqued herself upon the solidity of her reflections, “is a very common failing, I believe. By all that I have ever read, I am convinced that it is very common indeed; that human nature is particularly prone to it, and that there are very few of us who do not cherish a feeling of self-complacency on the score of some quality or other, real or imaginary. Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used synonymously. A person may be proud without being vain. Pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves; vanity to what we would have others think of us.”

No one acknowledges Mary’s statement, nor does it shift anyone’s views on the subject at hand.

- Neither Mr. Collins nor Mary completely fit into society. Both have trouble understanding and behaving appropriately in social situations, such as when Mr. Collins introduces himself to Mr. Darcy at the ball, and, at the very same ball, Mr. Bennet must stop Mary from performing on the pianoforte. Mary seems to have an innate social awkwardness and lack of awareness, and Mr. Collins’ deficits are caused, at least in part, by his upbringing and education.

- Mary is bookish, and Mr. Collins likes reading religious tracts and books.

- Mr. Collins is a clergyman, and Mary cares deeply about moral values.

- They are both judgmental. After Lydia runs away with Wickham, Mary declares,

“Loss of virtue in a female is irretrievable, that one false step involves her in endless ruin, that her reputation is no less brittle than it is beautiful, and that she cannot be too much guarded in her behaviour towards the undeserving of the other sex.”

And in a letter, Mr. Collins writes,

“The death of your daughter would have been a blessing in comparison of this.”

Ouch. That’s harsh.

As we consider these seven reasons, we find ourselves asking:

What better foundation for marriage is there than social ineptitude, bookishness, and a healthy dose of self-righteousness?

Mary and Mr. Collins do share some fundamental values, and both relate to people in a distinctive way. And this could be enough to argue that they would be well suited.

In Jack Caldwell’s novel The Companion of His Future Life, Mr. Collins does marry Mary Bennet. While the novel still focuses on the stories of Elizabeth and Jane, we see a fair bit of Mary, and both she and Mr. Collins seem quite satisfied with their choice. As a result of their marriage, Mary grows in new ways. She does not let Lady Catherine de Bourgh control her life, and goes behind her back to become close friends with Anne de Bourgh.

Arguments against a happy union between Mr. Collins and Mary Bennet, aka, why it’s a good thing he married Charlotte Lucas

- Being similar does not actually mean you are suited. Were they to marry, their similarities could cause them trouble in the future, particularly since they both struggle in social situations.

- Mr. Collins is actually a lot less bookish than Mary. He’s not as well read, and even Mary, with her inability to see how to apply her knowledge, can see that he is lacking in this area:

Though by no means so clever as herself, she thought that, if encouraged to read and improve himself by such an example as hers, he might become a very agreeable companion.

- Mr. Collins needs someone to manage him. He already follows Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s every suggestion. After his marriage to Charlotte, she helps him restrain some of his less-desirable tendencies in ways that make her life better:

To work in his garden was one of his most respectable pleasures; and Elizabeth admired the command of countenance with which Charlotte talked of the healthfulness of the exercise, and owned she encouraged it as much as possible.

Would Mary be able to do this in the same subtle yet effective manner? It is likely that she’d choose a different, more direct tact. Yet some of the reason Charlotte and Mr. Collins’ marriage works is because he does not feel any friction. At the end of Elizabeth’s six-week visit, Mr. Collins says:

“Only let me assure you, my dear Miss Elizabeth, that I can from my heart most cordially wish you equal felicity in marriage. My dear Charlotte and I have but one mind and one way of thinking. There is in everything a most remarkable resemblance of character and ideas between us. We seem to have been designed for each other.”

Unlike Charlotte, Mary is not strategic in being tactful, and Mary would likely directly tell Mr. Collins if she disagreed with him. This would create a very different marriage, one with the potential for conflict.

- Even after his marriage, Lady Catherine is the most important person in Mr. Collins’ life. Charlotte is willing to praise Lady Catherine, be quiet during large portions of meals with her, and ignore any difficulties she causes in her life.

While it’s possible Mary could do the same (and in Caldwell’s novel, she not only does that, but also manages to subtly influence Lady Catherine in ways that help her meet her own goals), it’s just as possible that Mary would follow the path of Elizabeth and state her mind to Lady Catherine. When Elizabeth speaks up to Lady Catherine, it causes great consternation on the part of Mr. Collins, and he would likely be even more upset if it were his wife disagreeing with her.

- Mary wants Mr. Collins to change (“to read and improve himself”). Could Mr. Collins change in a way that would suit Mary?

In her novels, Jane Austen is open to the idea of people changing, but this change generally happens before marriage. For instance, inspired by Elizabeth’s critique, Mr. Darcy lets go of his pride:

“I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle. As a child I was taught what was right, but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit….Such I was, from eight to eight-and-twenty; and such I might still have been but for you, dearest, loveliest Elizabeth! What do I not owe you!”

- A large part of Charlotte and Mr. Collins’ marital harmony is due to Charlotte’s ability to ignore that which she doesn’t like in her husband. When Elizabeth visits, she watches their interactions:

When Mr. Collins said anything of which his wife might reasonably be ashamed, which certainly was not seldom, she involuntarily turned her eye on Charlotte. Once or twice she could discern a faint blush; but in general Charlotte wisely did not hear.

Being able to largely ignore the little bothers in each other is of great service to other relationships as well (Mr. Bennet must do the same for Mrs. Bennet). This is something Mary would need to learn.

- Mary’s interests thus far have been to devote as much time to her studies and the piano as possible. She seems ill-prepared to manage a household, while Charlotte is ready and willing to do so. Mary would need to develop those skills and, by necessity of not having many servants, would need to take time from her books and devote herself to running a house. This is something she would need to learn if she ever marries anyone. But because it is something Charlotte already has mastered, and that she finds intrinsic value in, this is a source of joy for her.

When Elizabeth leaves after her six week visit, she reflects:

Poor Charlotte! it was melancholy to leave her to such society! But she had chosen it with her eyes open; and though evidently regretting that her visitors were to go, she did not seem to ask for compassion. Her home and her housekeeping, her parish and her poultry, and all their dependent concerns, had not yet lost their charms.

One of my favorite novels which explores Charlotte’s perspective, with its joys and struggles, is The Clergyman’s Wife. Even for Charlotte, even with her need for security, it is not an easy path.

In looking at these seven reasons, Mary seems ill-suited for Mr. Collins. Charlotte already has the perspective and the skills to make matrimony to Mr. Collins be as smooth as possible, while if Mary were to marry Mr. Collins, their path would be bumpy, at least at the start.

Reflections on Marriage: What we can learn from the marriages that did and did not occur

Any marriage requires give and take, and if the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet is a good indication, there are plenty of workable marriages in which the two individuals are not particularly suited for each other. Whether or not the pros outweigh the cons, or the cons outweigh the pros, ultimately Mary Bennet and Mr. Collins could have had a tolerable, successful, or perhaps even joyful marriage.

Regardless of whether they would have been suited for each other, Charlotte took the initiative and as a result, married Mr. Collins. From a story standpoint, this is powerful, because while Elizabeth doesn’t think highly of Mary’s life philosophies, Charlotte Lucas is her close friend. Charlotte and Mr. Collins’ engagement shakes Elizabeth.

When speaking to her sister Jane of Charlotte’s impending marriage, Elizabeth declares:

“It is unaccountable! in every view it is unaccountable!”

“My dear Lizzy, do not give way to such feelings as these. They will ruin your happiness. You do not make allowance enough for difference of situation and temper. Consider Mr. Collins’s respectability, and Charlotte’s prudent, steady character. Remember that she is one of a large family; that as to fortune it is a most eligible match; and be ready to believe, for everybody’s sake, that she may feel something like regard and esteem for our cousin.”

“To oblige you, I would try to believe almost anything, but no one else could be benefited by such a belief as this; for were I persuaded that Charlotte had any regard for him, I should only think worse of her understanding than I now do of her heart. My dear Jane, Mr. Collins is a conceited, pompous, narrow-minded, silly man: you know he is, as well as I do; and you must feel, as well as I do, that the woman who marries him cannot have a proper way of thinking. You shall not defend her, though it is Charlotte Lucas. You shall not, for the sake of one individual, change the meaning of principle and integrity, nor endeavour to persuade yourself or me, that selfishness is prudence, and insensibility of danger security for happiness.”

Later, when Elizabeth visits Charlotte and Mr. Collins, she comes to accept—perhaps even understand—Charlotte’s choice, despite knowing that she would never have been able to make such a choice herself. She thinks, “Poor Charlotte!,” but her anger for her friend’s choice has been replaced by melancholy.

Elizabeth does not adopt Charlotte’s outlook on life—if she had, she would have accepted Mr. Darcy’s first proposal, despite her dislike of him.

Mr. Collins and Charlotte’s marriage acts as a foil to Elizabeth’s ultimate decision to marry Mr. Darcy. Yet it also influences Elizabeth, and helps her have a more expansive perspective on life.

If Mary had married Mr. Collins, it would have been less likely to change Elizabeth in any significant way.

My Personal Stance

While I can understand the opposing perspective, personally, I don’t think that Mr. Collins and Mary would be particularly happy together. When I wrote my own continuation of Mary’s story, a trilogy which begins with The Secret Life of Miss Mary Bennet, I didn’t give Mary a romance in the first book, because I didn’t think she was ready for marriage. I felt like she needed to grow and develop, and figure out herself first, before she would be ready for a relationship. However, in the very first chapter, she does reflect on the fact that she did not have the opportunity to marry Mr. Collins: this is an event that has stuck with her and continues to influence her.

What do you think? Do you side with Jack Caldwell and others who see great potential in a Mary-Mr. Collins relationship? Or do you think that it would have been a bad choice for one or both of them? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Note: sometimes I used affiliate links to Amazon and other websites. When that occurs, I may receive a small commission, but at no additional cost to you.

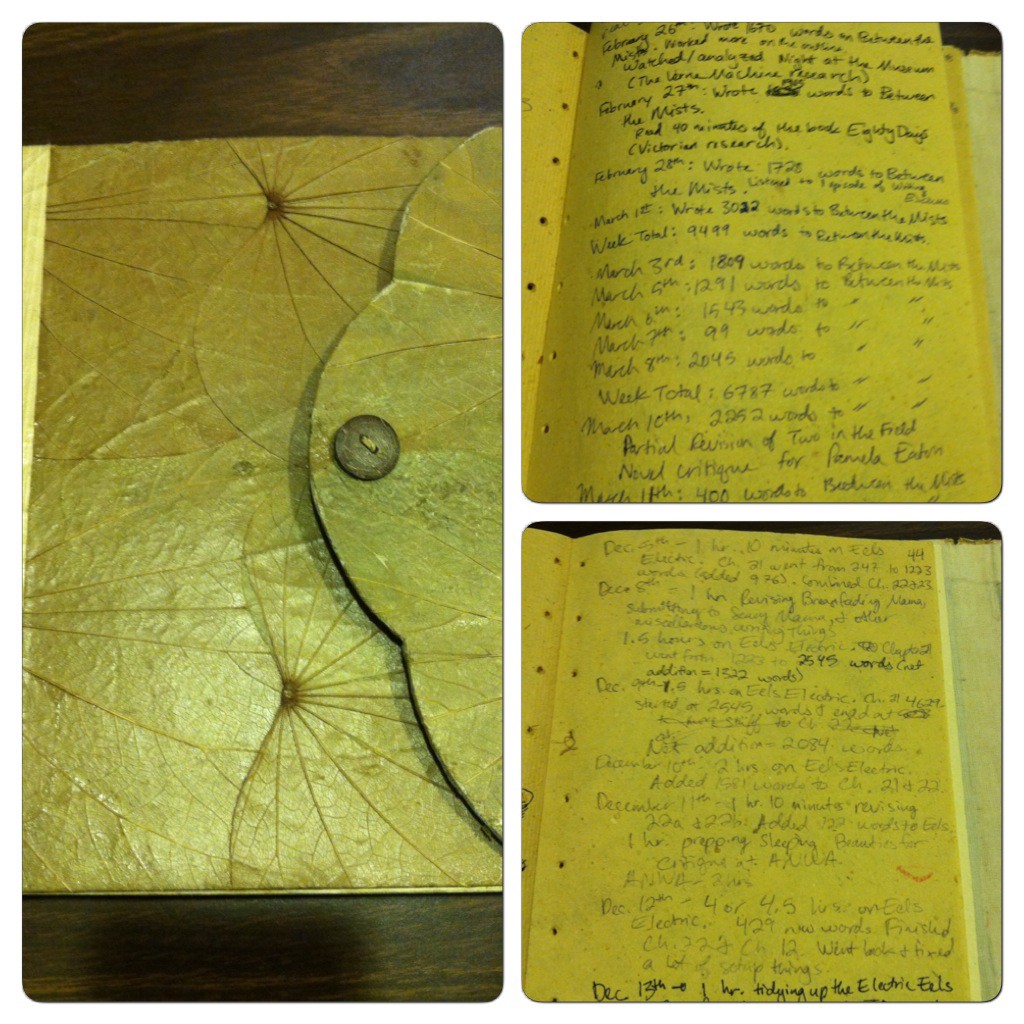

How and Why I Track My Writing Time (Using Toggl)

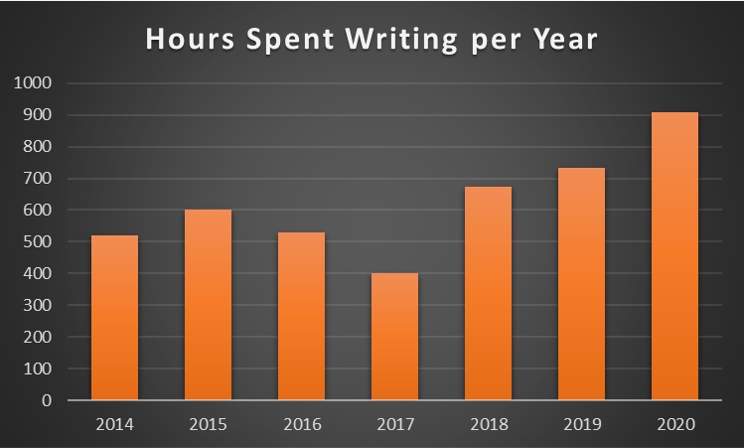

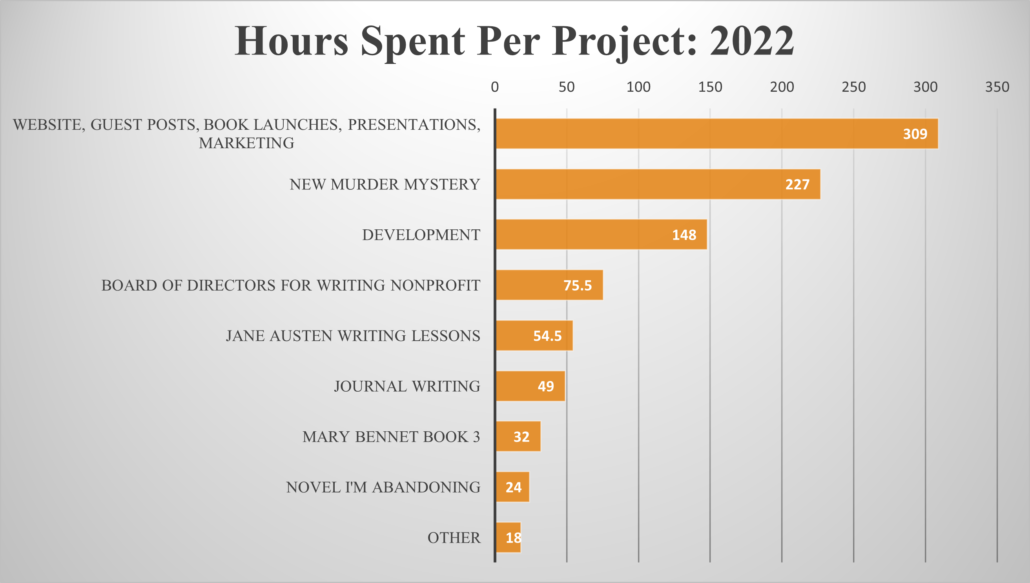

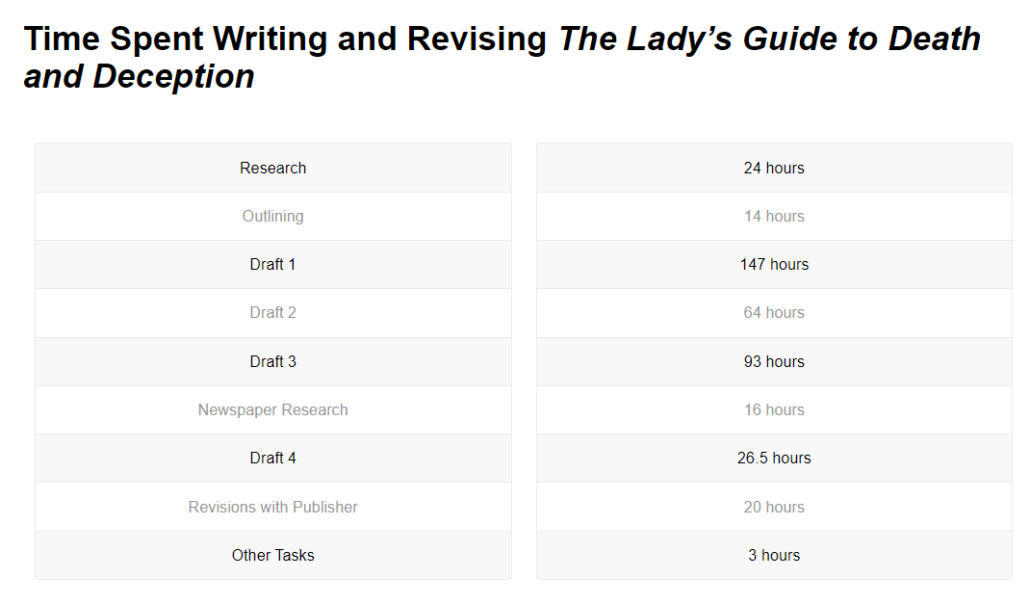

Since 2013, I have been tracking the time I spend writing. This has resulted in my glorious end of year posts, filled with charts on the number of hours I’ve spent, and calculations on exactly how long I spend on each stage of writing a book.

Every single time I post about the results of my time tracking, I get questions on how I track my time. So question no more: I’m about to tell you the hows and the whys of tracking my writing time.

First, Why I Track My Writing Time

I spent years not really writing consistently. While some writers can quite effectively write a couple times a month or year, for me this resulted in me writing 2-5 chapters of a number of stories and never finishing any of them.

Then a few things happened: I read the book The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg, which helped me think about turning writing into a habit, I attended a book signing by Shannon Hale, where she recommended that writers write regularly, and I read a blog post by Susan Dennard on keeping a writing journal. Feeling all-around inspired, I began tracking my writing time.

In doing so I discovered:

- Writing new words is only one small aspect of my writing process. Research, outlining, revisions—these are all essential to my writing process.

- All the other writing-related things I work on help me as a writer and count as writing too. If I read a book on writing, attend a writing conference, or critique someone else’s writing, it builds my skills as a writer.

- I am a slow writer. While I still sometimes do it, tracking daily word counts can be discouraging, while tracking my writing time helps me see my progress.

- Tracking my writing time holds me accountable. I’m less likely to waste time browsing social media or procrastinating writing when I’m going to log my time.

How I Track My Writing Time

From 2014 to 2017, I tracked my writing time using a notebook/writing journal. Every day I would write down what I did and how much time I spent on it. Or, if I didn’t do anything, I had to write that down.

It was really motivating. And it also resulted in a lot of manual math at the end of each year to figure out how much time I spent writing.

Then in the summer of 2017, I moved, and during the move I lost that year’s writing journal. I also stopped tracking time and almost gave up writing. As one does. (Did I really want to be a writer? Do I really have what it takes to be a writer? Don’t we all stand in front of the mirror and ask that on occasion?)

But then I kept writing.

In 2018 I decided to take the plunge and use a digital option to track my time: Toggl Track. And I’ve absolutely loved it.

Toggl Track

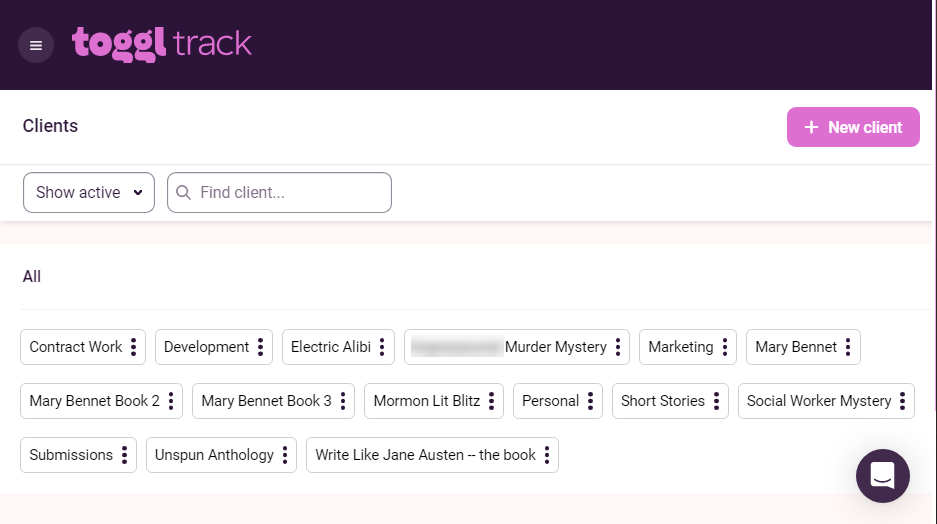

Toggl Track is a time tracking app that you can use in a web browser and as an app. What I love about it is how much it allows you to customize in terms of categories, projects, and tags, and how you can easily generate reports. The basic plan (which I use) is free, though with the paid version you can do extra types of reports, save reports, do more with teams, etc.

While I personally love Toggl, there are lots of other good time tracking apps out there. However, regardless of what you decide to use, the conceptual approach I took to customizing Toggl may be useful to you.

The Big Picture Categories

Toggl’s structure uses big-picture categories which you can subdivide into smaller task.

For Toggl, the big picture category is called a Client.

I use clients to for the big-picture categories of how I spend my time:

- Development

- Marketing

- Personal Writing

- Submissions

- Each novel that I write becomes a big picture category (for example, “Mary Bennet,” “Mary Bennet Book 2,” “Mary Bennet book 3,” etc.)

While “client” is very much a business-oriented approach to looking at these bigger categories, it reminds me that I need to put time into each of these things. Developing my writing, doing personal writing, submissions—these are each things I can feed by putting time into them.

Depending on the year, I spend more or less on each category. For example, when I was searching for an agent, the “Submissions” category needed a lot more hours. Now it only takes a handful of hours, for the few short stories I submit to publishers each year.

Breaking Your Big Picture Categories into Projects

Big picture categories help me to focus on my big picture writing goals—the larger areas of how I spend my time. But to be really useful, I need to create individual projects for each larger category.

In Toggl, each client can be given as many “projects” as needed.

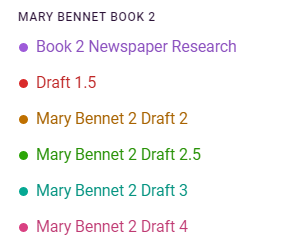

This is a pretty standard list of projects for one of my novels:

Each draft is a separate project. Research is a project. Outlining is a project. And apparently I accidentally created two separate newspaper research projects.

Here are the projects I created for my Development category:

These are each things that help me develop myself as a writer, or help me assist other writers on their own journeys.

Next, let’s look at the current projects in my Marketing category:

These projects are flexible—you can easily add new projects in a category or archive ones you no longer need. I need to retire the Book Reviews project, because I’m not using that at the moment. And “Twitter Outreach” needs to be combined with “Social Media,” because that’s how I’ve been logging it. (Note: I don’t log just any time I spend on Twitter and social media—that would be a slippery slope to doing more writing. Rather, I log things like creating book-related posts, participating in Twitter events like #momswritersclub, etc.)

Side Note: I haven’t done this, but with a paid subscription to Toggl you can get more granular and create Sub-Projects (projects within each of these projects, which are called Tasks).

Logging the Time: Descriptions and Tags

Once I have my big picture categories (clients) and projects set up to my satisfaction, I’m ready to time track.

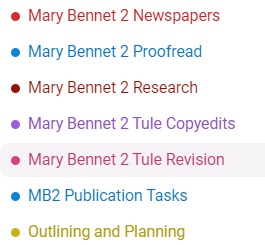

On a web browser, this is what the Track view looks like.

I select the Project (with its client) that I am working on, I type in a description of what I’m doing, and then I press the start button.

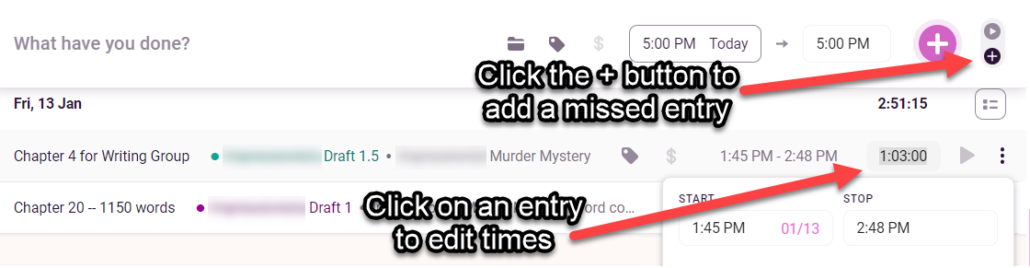

Editing and Adding Missed Entries

There are plenty of times when I forget to press either the start or the stop button, or forgot to track my writing time entirely. But it’s really easy to fix. I click the + button to add a missed entry or I click on an entry’s attributes to edit them.

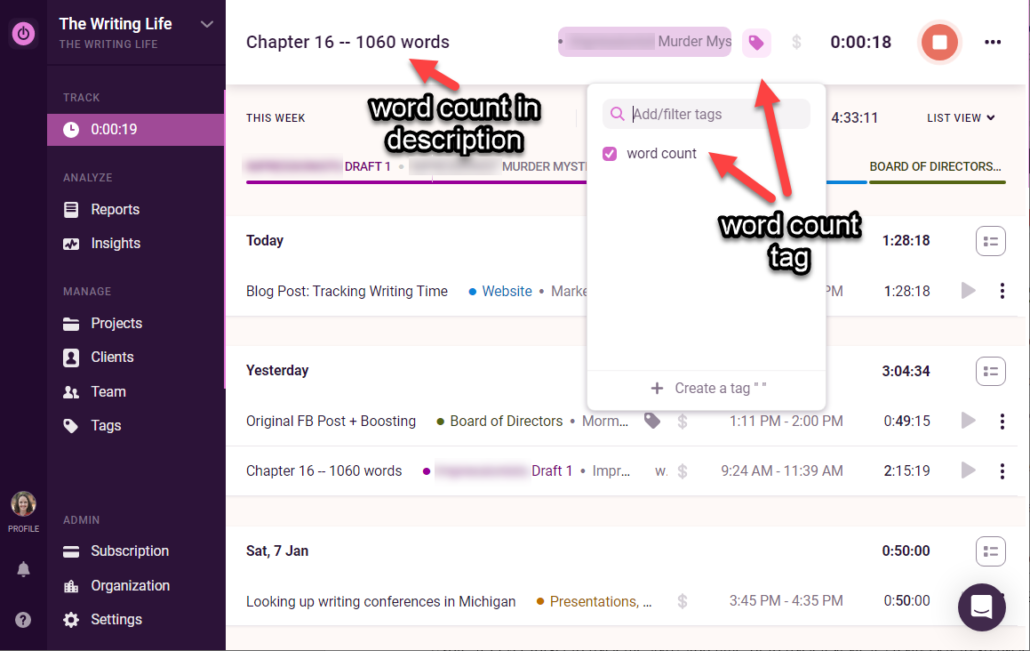

Tracking Word Count

There are a lot of dedicated word count trackers out there, and if you put a big focus on tracking your word count, you may want to use one of them.

Word count is not my focus, but I do track it when I’m writing a first draft. I just do this in Toggl. I write my total number of words written in the description, and then I add a tag for word count, to make it easy to sort for word count later in the reports.

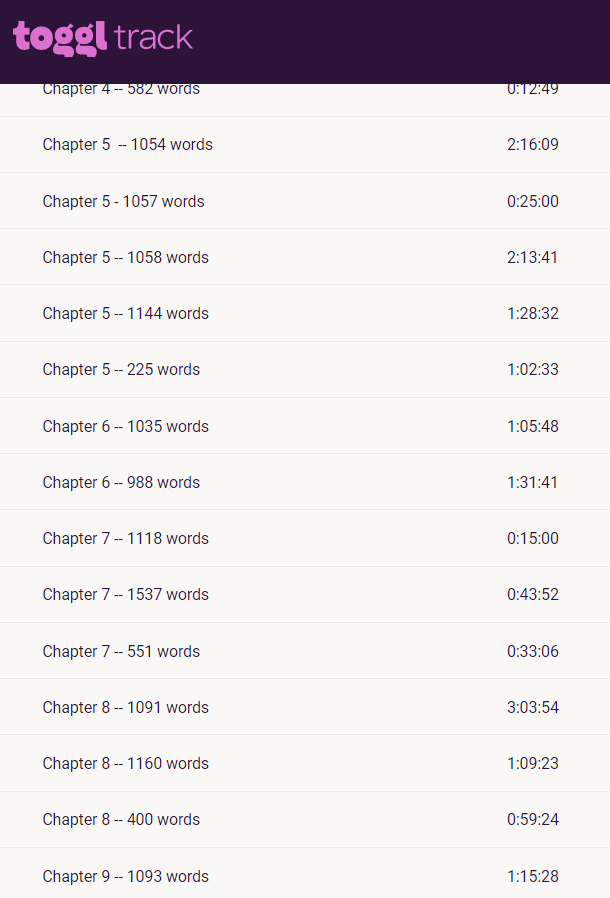

I pulled up the word count tag for the first draft of my third Mary Bennet novel, The Lady’s Guide to Death and Deception, and you can see different amounts written on different chapters (and if you click on an entry, you can get more detailed information, like the date):

Other Views and Reports

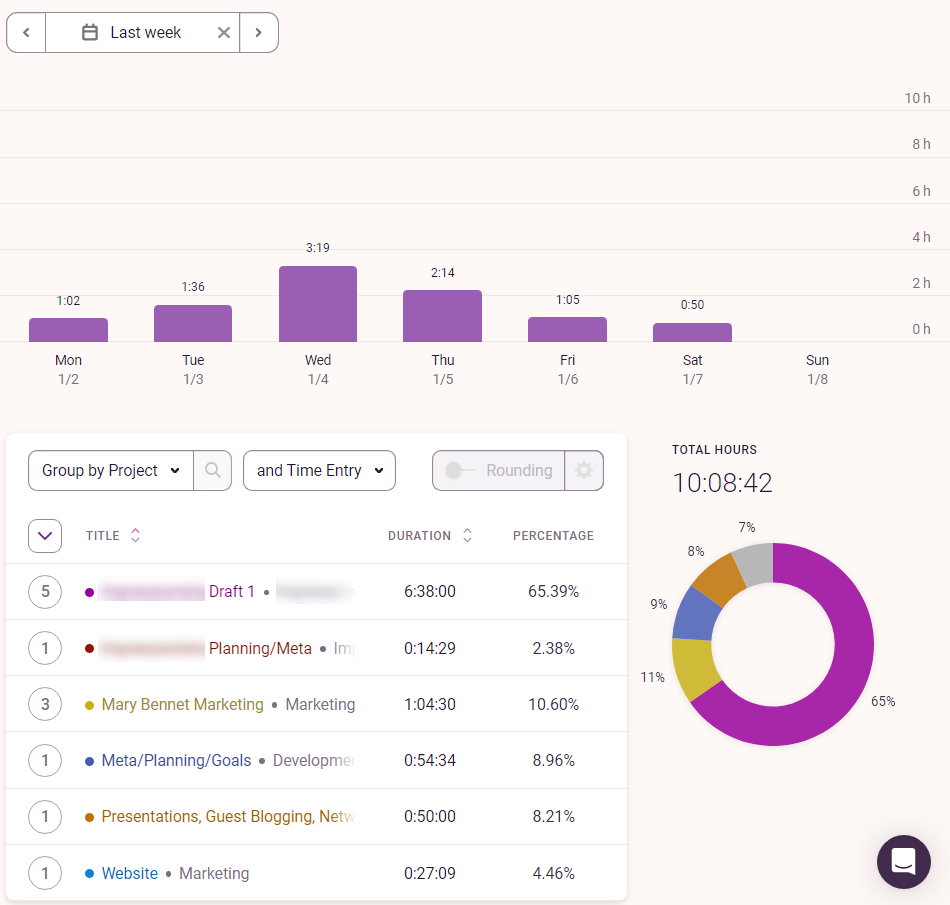

One of my favorite parts of tracking my time is looking at the Week View. This helps me to see my progress over the course of the week, and what I’ve been working on.

In addition to sorting by project, you can also sort by your clients/big picture categories.

One of my other favorite reports is the Month View:

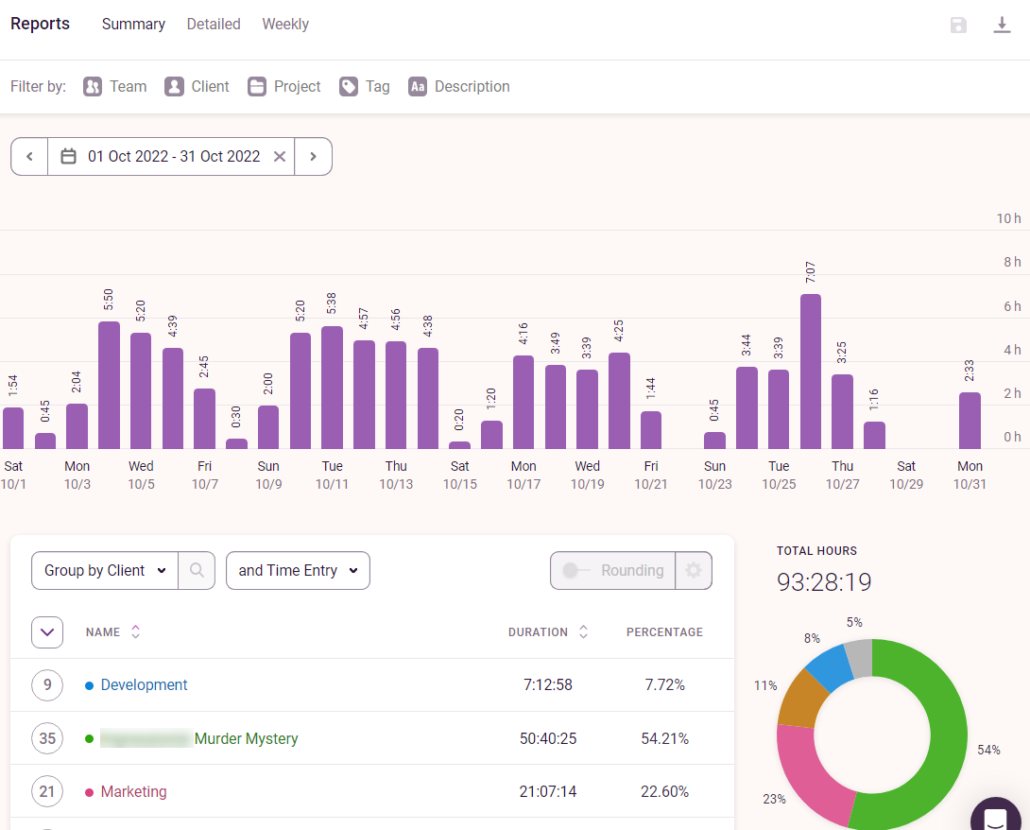

I like the month view for looking at my big-picture progress for the month. Over fifty hours on my current novel meant that I made lots of progress on the book. It also means that I didn’t let all my other types of writing tasks become more important than what I had selected as that month’s big goal.

Sorting for a Particular Client or Category (or for a Selection of Clients or Categories):

One of the most useful things about digital tracking is the ability to see more specific details about the time spent on just one segment of my writing time.

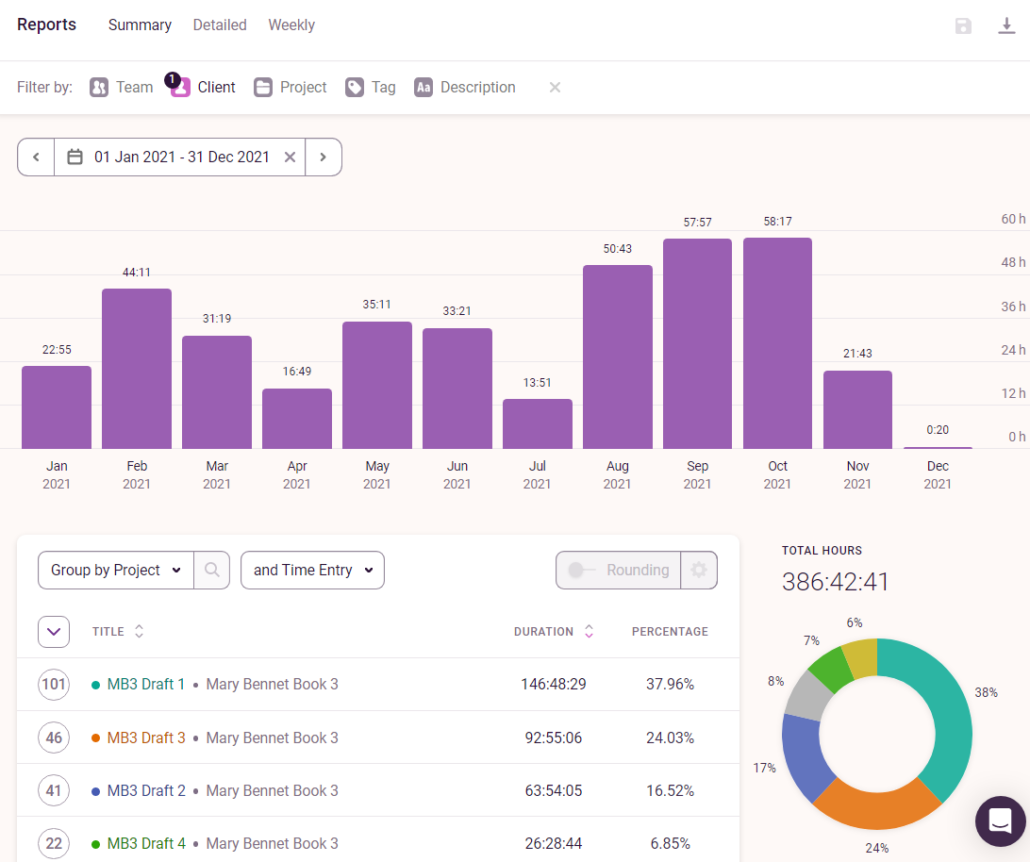

For example, I went to reports and set it for the year 2021. Then I selected three clients or big picture categories, “Mary Bennet,” “Mary Bennet Book 2,” and “Mary Bennet Book 3” so I could see the time spent that year on my entire Mary Bennet spy series.

I spent only 20 minutes on the first book in the series, 29 hours on the second book in the series, and 386 hours on the third book in the series.

However, this isn’t a full look at what I did on the series. The first Mary Bennet book was released in 2021, and I want to add in the time I spent related to marketing the book.

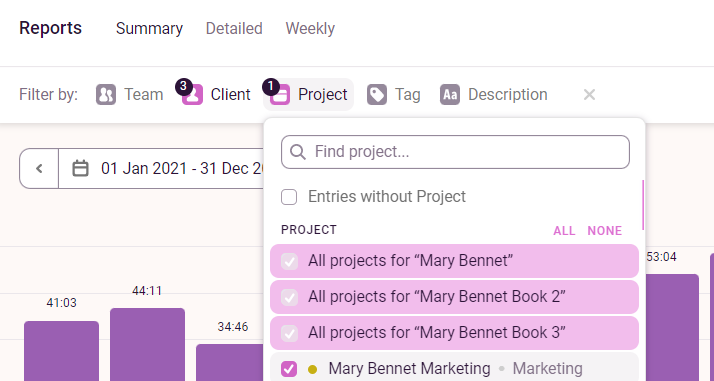

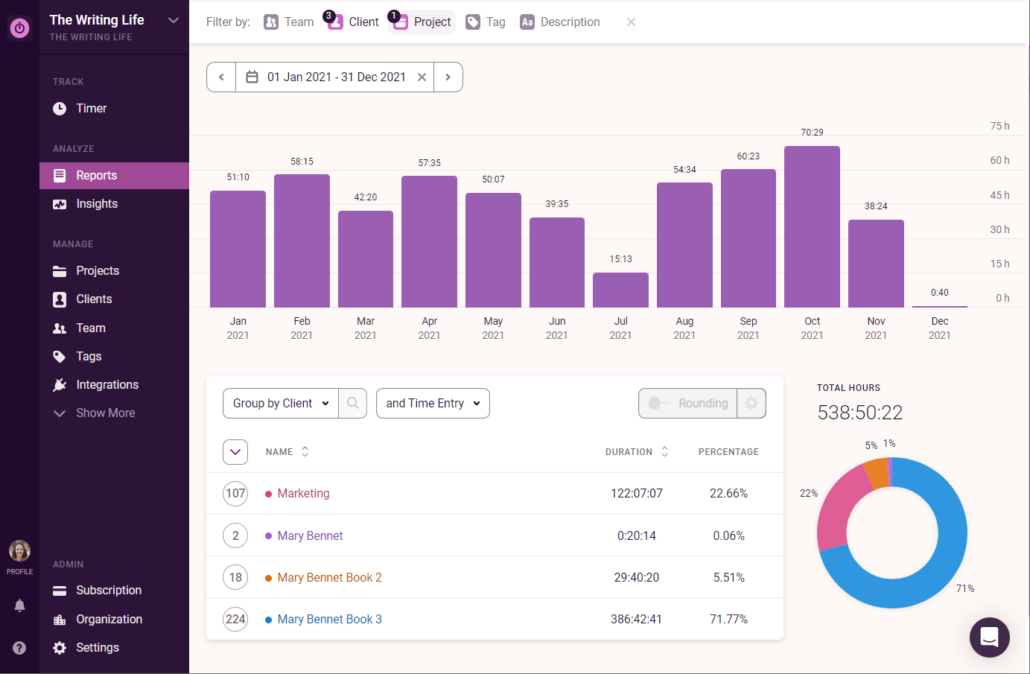

I leave the existing filters for the three Mary Bennet books, and then, under projects, I also select Mary Bennet Marketing:

This now gives me the full look at the time I spent both writing—and marketing—my Mary Bennet spy series during 2021.

As you can see, the time went up from 416 hours to 538 hours, because I spent 122 hours on marketing related tasks.

Moving Forward, One Hour at a Time

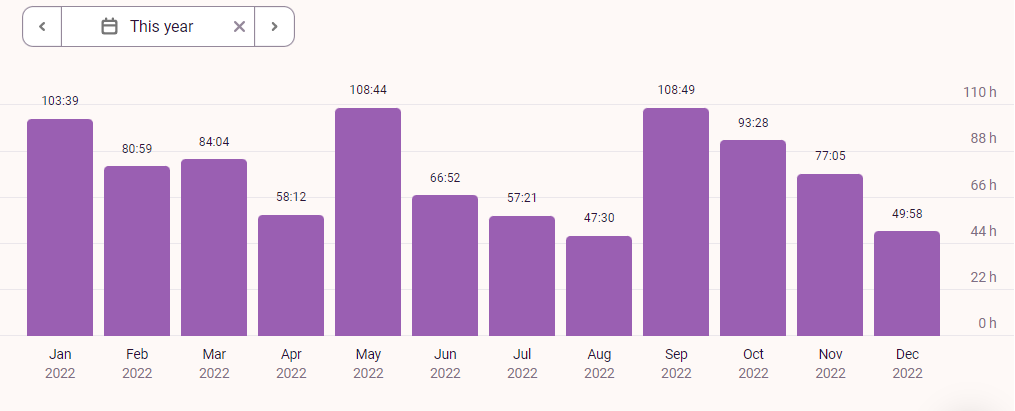

There’s so much that you can’t control about writing. You can’t control if your book will sell, or if it sells, if it will do well. There are ideas that have to be abandoned, periods of time where the creative well is dry and the muse has fled.

You can’t always even control how much time and energy you have to put towards writing. Life circumstances and other obligations can have a huge impact on what time you have to put toward writing. If this year continues in the way that I expect, I will likely have less time to spend writing this year than I spent writing in 2022.

But what I like about time tracking is that it helps me recognize how I’m spending the writing time that I have. Every hour I put towards my writing is a step forward—it’s a recognition is that I’m bringing my stories and dreams to life.

Have you tried tracking time or word count? Does it work for you? Do you a similar method, or do you use a different method? I would love to hear in the comments!